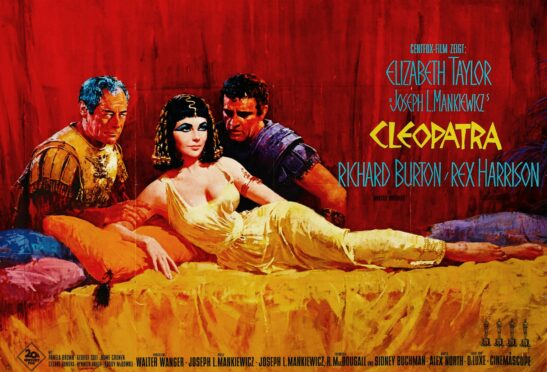

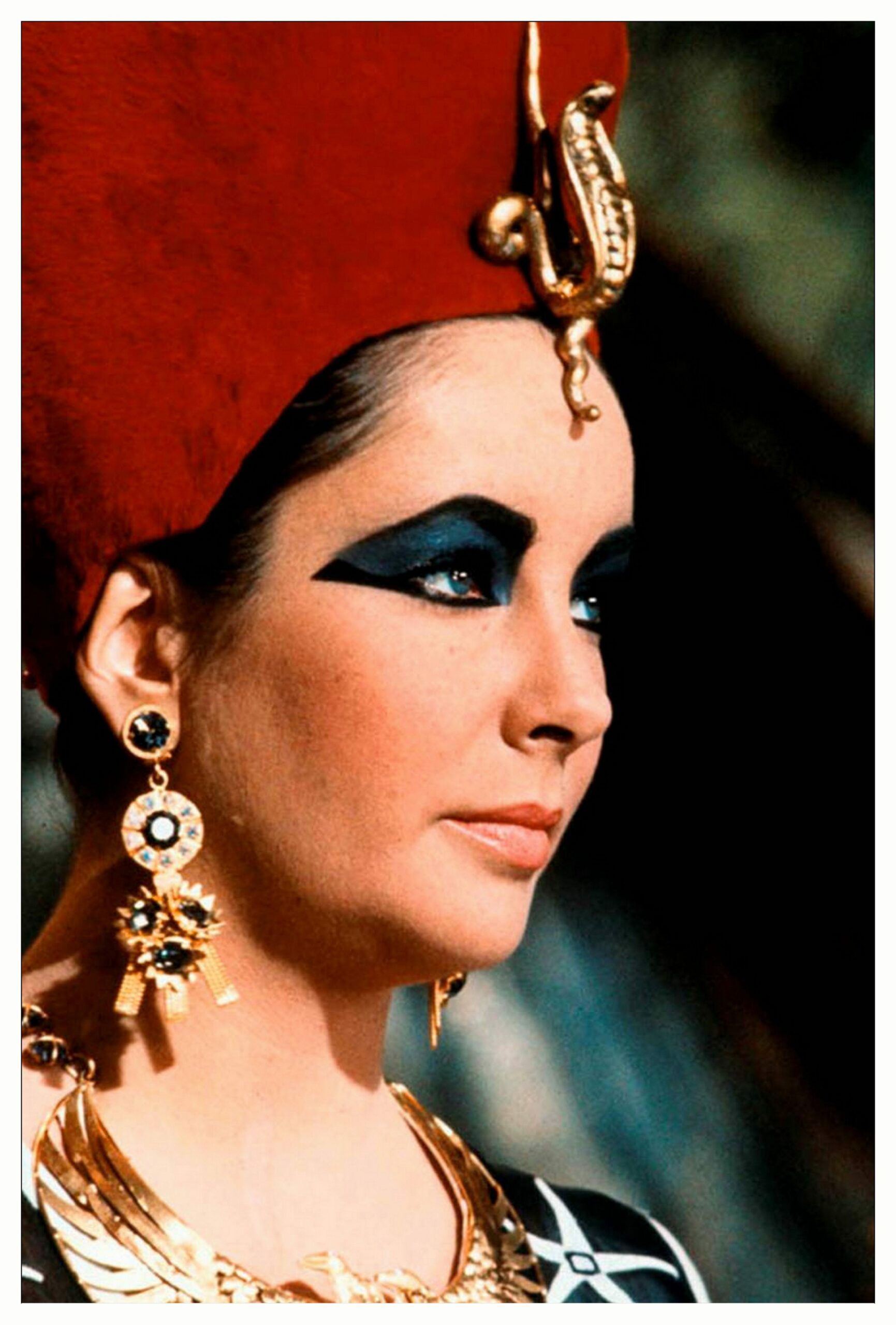

True but tragic, the love story of Antony and Cleopatra has inspired everyone from William Shakespeare to Elizabeth Taylor.

First recorded by scholars in ancient Greece and Rome more than 2,000 years ago, the affair of Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt from 69-30 BC, and Marcus Antonius, Roman politician from 83-30 BC, has been told on page, stage and screen countless times. The story of their three children – twins Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios and younger brother Ptolemy Philadelphos – has not.

Their daughter, a princess imprisoned by the Romans aged 10, rose to become a powerful African queen who successfully ruled a wealthy, cosmopolitan and important kingdom for two decades.

Now, in a first modern biography, Dr Jane Draycott, a historian and archaeologist at the University of Glasgow, is giving her a new voice and reframing the young queen as a modern icon for feminists and women of colour.

The academic believes the young queen – who went on to marry a black African royal and have her own mixed-race child – may have had a mixed-race heritage.

Draycott said: “Cleopatra’s daughter was an influential figure. She was a queen in her own right, ruling an important kingdom Macedonia on the periphery of the Roman Empire. By looking at her, we can see that what we have been told about ancient history, that women were only wives and had babies and had no power or agency, is not right. While scholarship has focused on great men, there were great women too but they have been overlooked, ignored and removed from history.

“For women – and women of colour – Cleopatra Selene is a great example of how we have always been there, doing interesting and important things, how we have always had our own power and prestige.”

Draycott – fascinated by history and archaeology from a young age and inspired in her teens by the BBC show Meet The Ancestors – started working on the biography in 2018 and, in the book, explains: “How does one dare to attempt to write a biography of any ancient historical figure, let alone an ancient woman?

“Unlike their medieval and modern counterparts, in the vast majority of cases ancient historians have no letters, certainly no diaries, and only very rarely the historical figure’s own words, recorded verbatim, to rely on as source material. The literary, documentary, archaeological and even bioarchaeological evidence that one might attempt to use as source material is highly suspect. It is buried deep under thousands of years of chauvinism, sexism and even outright misogyny.”

Draycott uses as her starting point a large silver bowl depicting what is believed to be the face of the young queen. Excavated in 1895 from a villa just outside Pompeii, it was part of a large, important haul, buried under layers of ash and pumice after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD.

She said: “It was like a historical treasure hunt, going from record to record and object to object, and gradually building up this life. Cleopatra Selene was raised in Alexandria at the Royal court and given a fantastic education.

“But when she was 10 her parents lost their war with Octavian, the nephew of (the assassinated Julius Caesar) and Antony’s rival for control of the Roman Empire. So Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide. Cleopatra’s eldest son, Caesarion, who was the son of Julius Caesar, was executed.

“Their kingdom was annexed by Rome who wanted to use it for its wealth. Selene and her brothers were taken back to Rome as foster children and prisoners. Her brothers seemed to have died quite young, probably because of malaria or some other illness. She was the only one left of the family – the insignificant girl who couldn’t do anything politically or militarily as far as the Romans were concerned.”

But she could marry, and did, at around age 15 to a young North African royal named Juba who had also been brought up in the Roman court after the death of his father, the King of Numidia, who had lost in a war against Julius Caesar.

“It seems they had a good partnership where they worked together,” said Draycott. “It was unusual for it to be acknowledged that wives had an equal say in matters and as much power as their husbands. But Cleopatra Selene had the more prestigious ancestry and the more important relations.

“She was the one who was really providing the prestige, authority and power in the relationship. There were a lot of things she did in the kingdom that we don’t usually see women of that period doing. For example, she issued her own coinage. She was quite a trailblazer.”

They ruled for almost two decades until Cleopatra Selene’s early death at the age of 35 which, according to a poem written by Crinagoras of Mytilene, coincided with a lunar eclipse, which would place it on or around March 23, 5 BC.

Juba ruled for the rest of his life with the son of his first marriage, Ptolemy, who in turn ruled for around 20 years until his murder by order of his cousin, the then Roman emperor Caius Caesar, known as Caligula.

Cleopatra’s Daughter: Egyptian Princess, Prisoner, African Queen is published by Head of Zeus

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Hollywood Photo Archive/Mediapun

© Hollywood Photo Archive/Mediapun