Thursday March 13, 1941, had been a beautiful day in Clydebank – dry, sunny, the first bashful daffodils – and, after school, after their tea and till well after dusk, nine-year old Brendan Kelly played football on Jellicoe Street with his big pal, 13-year old Tommy Rocks.

But, bedtime beckoning, they abandoned their game and sat at the tenement door, marvelling as the great full moon rose over the town, illuminating every highway and the shimmering Clyde itself.

“God,” breathed Tommy. “Look at that moon. If Jerry comes tonight, he cannae miss…” Jerry did come, that very night; the Clydebank that had retired to sleep was all but obliterated – and, as he painfully recalled in 2011, little Brendan never saw Tommy Rocks again.

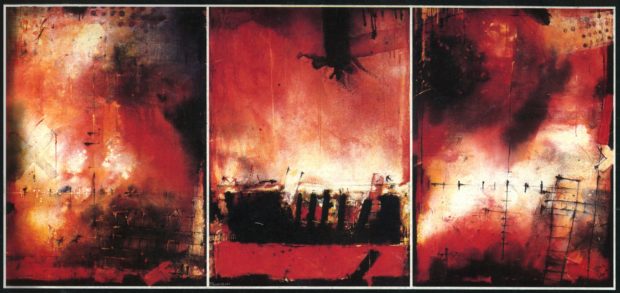

The Clydebank Blitz remains the single greatest disaster in modern Scottish history. Over two successive evenings, some 236 German planes subjected the town to pitiless saturation bombing. The attack was of such intensity that the explosions could be heard in distant Bridge of Allan; the glow in the night sky, as Clydebank burned, visible from Aberdeenshire, from the Inner Hebrides, and even from Ireland.

Officially, 528 people were killed – though, as one incredulous firefighter snapped, when advised of this, ‘On which street?’

To this day, many believe the death toll was far higher. Some 617 were seriously injured and, of 12,000 dwellings, only seven were entirely undamaged. A total of 4,000 homes were utterly destroyed; 4,500 were uninhabitable for months.

But that was academic because, by the evening of Friday, March 14, as the Luftwaffe returned with a second helping, only 2,000 folk remained.

More than 40,000 had fled, or been evacuated, most with no more than the clothes they stood in. Many would never return and, all those sundered bonds of community and neighbourhood apart, Clydebank was never properly rebuilt.

The bombers destroyed schools, shops, churches – Presbyterian and Catholic and Episcopalian. Clydebank had boasted a large Highland community, with Free Church and Free Presbyterian ministers holding regular Gaelic services: the little halls were reduced to rubble, and Gaelic was never preached again, for most of the Gaels fled, never to return.

And to this day – it is especially evident from a plane approaching Glasgow Airport – Clydebank, geographically and architecturally, is a town that does not make sense. Truncated Victorian tenements, scattered and ugly constructions from the 1960s and 70s, conspicuous gap-sites and nothing one could dignify as a thriving high street.

When Patrick Rocks sped home from his night shift in terror – it is said he actually swam across the Forth and Clyde Canal – to his tenement block at 78 Jellico Street, it was no longer there. Under a smouldering crater of Locharbriggs stone lay the remains of 31 people, slain by a single bomb.

And they included his wife, his mother-in-law, six of his sons, two of his daughters, and five of his grandchildren. Later, summoned to identify the bodies, he took one look at what the blast had done, and fainted.

There are things the sadly dwindling band of Clydebank Blitz survivors still cannot forget. The terrifying sounds of the attack; the rumble of still more incoming Junkers and Heinkels.

The smell – the taste – of dust and soot. The bodies, everywhere, disembowelled, limbless, mangled to obscenity. Folk screaming out of high windows in blazing buildings, moments before they disintegrated…

The difficulty, later, of getting away, of getting out, through streets choked with rubble, with burned-out tramcars. The lost, homeless, terrified dogs roaming everywhere; the men grimly recovering bodies – with baskets, for bits of bodies.

The inevitable looters, from Glasgow. And the squalid funeral, days later, at the vast mass-grave in Dalnottar cemetery, without even the dignity of cardboard coffins – corpses merely wrapped in sheets, knotted with string. Or the cellar beneath a Dalmuir pub, where dozens had taken fearful shelter – and then the pub took a direct hit.

The authorities did not even bother to recover those bodies, minced beyond any identification; they just poured in quicklime. For years afterwards, people were still happening on overlooked human remains.

Small boys, as late as the 1950s, found skeletons in the ruins of the Ben Bow Hotel. About 1962, an 11-year-old lad at play found one skeletal finger. It troubled him and, after much thought, he put it in a matchbox and gave it reverent burial.

When approached for television interview today, survivors – the mass of them, in 1941, just small children – still marvel how frequently they are asked to share photographs of the kin they lost in the Blitz; how such fatuous researchers still do not get it. There are no photographs of granny, or Dad, or Jim, or Agnes. Do people not understand that they lost everything in the bombing?

Clydebank, in hindsight, had always been an obvious target for the Germans. It was a vital industrial town – surely the only community in Britain actually named after a limited company, and raised by the Clyde Bank Ship Yard only in the 1870s. By 1941 it was home to a rake of shipyards and factories, many central to the war effort, and – critically – of densely packed population, the mass of folk living in tenement-canyons.

Many Clydebank folk would love to know why, in March 1941, the town was so poorly defended: why anti-aircraft guns nearby fast ran out of ammunition, why RAF fighters circling overhead were repeatedly denied permission to engage with the enemy.

And why, in contrast to many other bombed British towns, there was so little post-war reconstruction. One local enjoyed a holiday in Germany about 1964 and couldn’t get over it – the streets immaculate, folk obviously well-off, shops full of fine things, jewellery, leather goods – “and there we were back home in Clydebank, still sitting in the rubble”.

But most bewildering is the great forgetting. As Home Front historian John Calder bleakly recorded in 1969, Clydebank “had the honour of suffering the most nearly universal damage of any British town”. Yet few books about the Blitz even mention the town and its ordeal.

A big part of that, of course, is the tendency of so many who do not know the town to conflate Clydebank with the generic “Clydeside”, red or otherwise. But the Blitz iconography engraved in the national consciousness, too, is of the likes of London and Coventry – not least because, at the direction of the laughably named Minister of Information, their blasted streets and indefatigable citizenry were exploited for propaganda purposes.

But its panjandrums censored any mention of Clydebank – and certainly the scale of destruction and loss of life – from the newspapers.

There were but vague reports of some bombs on a town in the west of Scotland. A photograph of that mass-grave was cropped, at censors’ orders, so its sheer size was not apparent.

A detailed account of the attack by one survivor was intercepted by the authorities: his letter would not surface till 1971. Neither Prime Minister Winston Churchill nor any national figure came to console Clydebank: the future Queen Mother never had to look it in the face.

The decision in high places was deliberately to conceal the relative success of the raid – relative, because not one yard or factory was significantly damaged – from the Germans, lest they try again; and to keep Clydebank going as a workshop of the war.

Striking workers were lured back; temporary homes knocked up; extra sugar rations. Some young men even ambled in for their shift from tents in the Kilpatrick Hills.

But there were deeper, darker reasons. Whitehall and the Scottish Office had convinced themselves Clydebank was a hotbed of Communist sedition. And there was a real fear of igniting Scottish nationalism – and by no means unfounded: early in 1945, the SNP would win its first parliamentary seat.

So the government and the nation turned their back on Clydebank and its people – and, eight decades on, few have any idea what befell the risingest burgh in Scotland.

River of Fire: The Clydebank Blitz by John MacLeod, Birlinn, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied