Throughout history, it has been one of the most important weapons in our wardrobe. Used to subvert and shock, protest and portray personality, how we wear colour can often be just as powerful as words or actions.

Today, in particular, says author and fashion expert Caroline Young, is a time of bold choices, not least because our clothing can be used to subtly comment on world affairs or show unity with political causes.

“When I was watching Joe Biden’s inauguration, it was quite noticeable the bold colours of coats and the symbolism they represented,” explained Young, who has previously explored the history of fashion with her books Classic Hollywood Style and Style Tribes. “The Democrats, like Michelle Obama, for example, were wearing purple because it’s red and blue together, creating an idea of unity.”

Inspired by the colourful outfits worn by women while Biden took the oath of office, Young’s new book delves into the power of colour, and why it has been woven into the history of not just fashion and films, but society and politics, too.

Exploring how pigments and dyes can mean so much more than meets the eye, The Colour Of Fashion uncovers our decades-long shared obsession with colourful clothing through 10 shades starting with, perhaps controversially, black. Young said: “It’s kind of a blank canvas. Black takes on all these different meanings. You can wear it with different colours, it goes with everything, and it’s considered to be slimming. Plus, you can wear it to blend in or to stand out – it’s really adaptable. That’s why it’s so popular.”

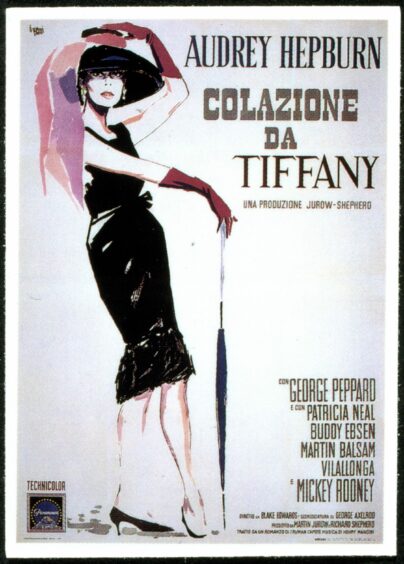

She explains that “true black is the absence of colour” and outlines how the Gothic shade, considered the world’s oldest pigment, has been used throughout history to represent everything from suffering – as it was during the Middle Ages when the Black Death swept throughout Europe – to the puritan religious values of the 17th Century. Then, of course, there is the classic sophistication of the Little Black Dress, as worn by Audrey Hepburn in 1961’s Breakfast At Tiffany’s.

Black, she found during her extensive research, has always been one of the most compelling colours. Young continued: “In Renaissance portraits, black was one of the powerful colours that people would wear. It was a symbol of virtuosity, so a lot of religious figures would wear black, too.

“Colour in portraits was hugely important because, while you couldn’t always tell what the fabric was, you could tell the colour of what people are wearing.

“Some people wear black because it is a serious, sombre colour so it’s a powerful tool when you’re making a political statement as well.”

The varying symbolism of colour, whether depicting emotions or allegiances, wealth or status, is perhaps most apparent in Young’s research into green – her favourite chapter of the book. Simultaneously able to convey nature, sexuality, luxury and even poison, the natural shade has been evocative since as far back as the Egyptians and Romans, whose Latin word for green, viridis, translates to “young”, “fresh”, “lively” or “youthful”.

However, it is the use of green in Hollywood that most interested Young. She explained: “Through my research, I found there was a lot of symbolism in green. In the book, I talk in particular about what green means in films, and how it can represent dreams and hopes – like in The Great Gatsby, which sees the character always looking at that green light.

“In films that deal with the pursuit of stardom, green light or green dresses and green costumes are often used as indicators, as it is in La La Land. In Singin’ In The Rain, too, Cyd Charisse wears this really absinth-coloured green dress when she is trying to lure Gene Kelly, while also being this unattainable vamp as well.

“Green has symbolism, from health and environment to being poisonous and toxicity. It’s so interesting just how many different meanings one colour can have.”

Ultimately, Young argues, colour has always been used to tell a story, particularly our own.

“When we do choose clothing, often we’re just picking out something comfortable or something that’s already in our wardrobe,” she said. “We don’t often think about making a political statement. But colour can be used to deliver a message, and it does that subliminally as well. If you go for an all-pink outfit, for instance, people are going to have a certain opinion of you or if you’re wearing orange, it’s really going to attract attention.

“It can seem frivolous at the moment, given what’s happening in the world. But wearing colours is also simply a way of lifting mood and trying to be positive.”

From the book: If pink is for little girls, it wasn’t always

Prior to the 20th Century, infants had worn simple white gowns for practical reasons – they were cheap, and could easily be boiled and bleached. Gender-coding of pink and blue didn’t become popular until the post-Second World War baby boom, writes Caroline Young in The Colour Of Fashion.

In Little Women, Louisa May Alcott writes: “Amy put a blue ribbon on the boy and a pink on the girl, French fashion, so you can always tell.” This suggests that the classification of pink for girls was a French innovation, yet the origins are unclear. By 1890, this concept still hadn’t travelled across the Atlantic. That year, Ladies’ Home Journal noted: “Pure white is used for all babies. Blue is for girls and pink is for boys, when a colour is wished.”

Similarly, in an article on baby clothes in the New York Times in July 1893, readers were advised to “always give pink to a boy and blue to a girl” because “the boy’s outlook is so much more roseate than the girl’s…that it is enough to make a girl baby blue to think of living a woman’s life in the world.”

In her 2012 study of the clothing of children in the United States up to the age of about six or seven, Jo Paoletti identified when girls were assigned pink, and boys were assigned blue. She noted that Sigmund Freud introduced the idea that very early experiences unconsciously shaped our adult natures, particularly our sexual desires. With the publication of further psychological studies on the subject of sexual identity in child development, this led to the belief that a child’s gender should be reinforced as early as possible.

By the late 1940s, feminine details were purged from the clothing of little boys, particularly pink. This was because there was a belief that masculinity in baby boys should be protected and reinforced to ensure they were not harmed by being mistaken for a girl which, so the thinking went, would lead to “dangerous” homosexuality.

In 1941, Dr Leslie B Hohman wrote of the dangers of “Girlish Boys and Boyish Girls”, as his article was entitled, in Ladies’ Home Journal. He gave the example of a 12-year-old boy whose mother was concerned he was displaying too much “girlishness”. Hohman sent the boy to military school to retrain him as “a normal manly youth”. Blamed for this excessive femininity was his mother’s “admiring notice at 18 months when he stroked with apparent delight a pink satin dress she wore”.

Similarly, girls were given pink to ensure they were sufficiently feminine, in order to fulfil roles as wives and mothers.

Second-wave feminists in the 1970s targeted pink as a colour that pigeonholed girls and stymied their potential, and instead promoted unisex clothing for children, in gender-neutral green and orange. However, this led to a backlash.

During the 1980s, pink was reinforced as a girls’ colour for both clothing and toys and this was enhanced by new prenatal technologies. Ultrasounds revealed to parents the sex of their child during pregnancy and they could shop for, and be gifted, the appropriate colour.

The Colour Of Fashion: The Story of Clothes In 10 Colours, Welbeck

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe