An apology to the miners wrongly arrested on the picket line during the 1984 strike must only be the start, according to Richard Leonard.

The MSP and former leader of Scottish Labour is calling for compensation to the strikers who, because of their criminal conviction, lost redundancy payments, pensions and the chances of securing new jobs.

Proposed legislation to be discussed by MSPs at Holyrood next week would pardon the men but Leonard says that is not enough. He is campaigning on behalf of the 1,400 miners arrested, the 500 men convicted and 200 sacked for protesting against the pit closures and is calling on the Scottish Government to step up and compensate those who were unfairly endured the consequences of an unwarranted arrest.

The government has so far refused to consider paying compensation but Leonard asks: “If not the Scottish Parliament, who? There was a distinctive Scottish dimension to the way the miners’ strike was policed up here.

“Miners were arrested by Scottish police, prosecuted by Scottish procurator fiscals and sentenced by Scottish sheriffs in Scottish courts.

“This isn’t about employment law, it’s about the criminal law.

“Don’t let anyone tell you it is ‘for Westminster’ to resolve this. Scotland can and must right these wrongs, including with compensation, so we can hold our heads high and know we finally gave these families the full justice they have deserved for so long.”

Coal had been mined in Scotland for hundreds of years, and at its height the industry had almost 200,000 miners working in the pits. Until 1843, children as young as eight were put down the mines, with one life lost for every 70,000 tons brought up from the dank darkness.

By the time of the year-long 1984 strike, Scotland still had more than 100,000 miners but the industry did not survive the dispute, leaving accusations of wrongdoing on all sides.

The mines were privatised within a couple of years and one by one they eventually closed as Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government scrapped the National Coal Board in 1987.

The last active deep mine in Scotland was at Longannet, Fife, which closed in 2002 when major underground flooding left its owners facing receivership.

In 2020, the Scottish Government said it would pardon the miners arrested in 1984 after an independent review. Humza Yousaf, then Scottish justice secretary, said the planned legislation would deliver a collective and posthumous pardon to help provide closure to mining communities and the officers involved.

“This was a bitter and divisive dispute,” he told MSPs. “Although three decades have passed, scars from the experiences still run deep. In some areas of the country, the sense of being hurt and being wronged remains corrosive.”

The feeling of betrayal at how we were treated has never left us

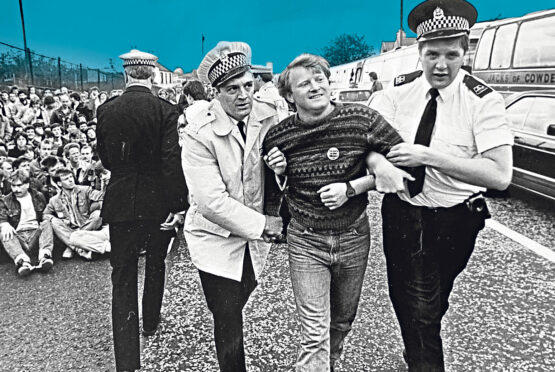

Two police officers are restraining him, others are ringing his fellow strikers sitting on the road behind him, a badge on his jersey promises Victory to the Miners, it’s May 10, 1984, and James Tierney is being arrested for the first time.

He would be arrested another three occasions before the seismic, year-long industrial dispute would end, with pits closed, communities in tatters and hundreds of strikers, like Tierney, facing the consequences of a criminal conviction.

Proposed legislation soon to be discussed by MSPs would formally pardon the 500 miners convicted of criminal offences linked to the strike. The Miners’ Strike (Pardons) (Scotland) Bill follows an independent review, led by John Scott QC, into the impact of policing on Scottish communities during the strike.

However, for many, a pardon is not enough for unfair convictions that cost them redundancy payments, pensions and, for some, the chance to work again.

Tierney, now 66, from Dunfermline, can still detail the day the photograph was taken after police stopped a bus full of strikers on the way from Fife to picket Ravenscraig steel works in Motherwell.

In a change in tactics, Strathclyde Police stopped the fleet of buses the day after the UK cabinet discussed the strike. The miners refused to say where they were going, spilling onto the A80, linking arms and sitting down in protest until, one by one, they were taken to the cells in Glasgow.

He said: “We didn’t know it then, but that day changed everything. We now know Maggie Thatcher and her cabinet were furious not enough arrests and punishments were being handed out. It’s always been believed orders were passed down the line to ramp things up.

“I was one of the strike organisers, bringing 300 miners from West Fife, Clackmannanshire and Stirlingshire to Ravenscraig Steel works in Motherwell to protest over imported coal being brought in to keep the plant working.

“It was an unprecedented move for the police, that day, when they stopped the strike buses at Stepps. It was a turning point, laying the foundation for what was to follow.”

Scotland would record some of the highest arrest and conviction rates in the UK during the strike and a conviction meant a miner would be sacked, losing out on any redundancy or pension payments. Charged with various minor offences, none of the men arrested at Stepps, including Tierney, ever appeared in court, although the move ensured the names and addresses of strikers were taken for the record.

Seven months later, Castlehill Colliery miner Tierney was arrested again, and this time he was charged over an altercation with a bus taking strike-breaking miners to the pit.

It ended with him spending weeks in Barlinnie prison, losing his job, redundancy and pension as well as leaving him with a criminal record. He said: “The scab bus carrying strike breakers passed by five of us at 5.30am on November 26, 1984, while we were just sitting outside the Fishcross miner’s welfare waiting to go off to our picket lines.

“We did nothing, but some younger lads coming from Sauchie passed by the bus 100 yards further down the road and stones were thrown.

“I’d already been arrested three times before, and it was known I was a strike organiser, so even although I wasn’t near the scab bus, I was picked up along with the four others who were with me. We were taken to the cells and then to Alloa Sheriff Court for a trial which lasted five days.

“There were 15 witnesses including the working miners on that bus who all said none of us did anything, but two policemen stood up and said they saw us.

“Out of the five of us, only one was found not guilty.

“The judge took just 30 seconds to sentence us.

“I spent 26 days in Barlinnie and was fined around £600 which was a huge sum back then. Of course I was sacked, lost my pension and any redundancy money. It would be another six years before I was able to retrain and start working as a teacher, so it’s hard to put a financial value on all I lost.

“I was luckier than others as my wife was a trainee teacher and that kept us going. Many families were never the same again. The feeling of betrayal and anger at the way we were treated has never left the communities hit hardest. The strike wasn’t just about the miners.

“It was about the end of the trade unions, the end of the heavy industries which had been Scotland’s bread and butter for generations.” Tierney eventually became faculty head of maths and business at Grangemouth High School but he still burns with the injustice of what was done to the miners.

He said: “We knew once the government broke the miners, they would turn on all the other unions.

“It’s only now that people are beginning to understand this is how we’ve ended up with dreadful things such as zero-hour contracts and people working as carers for little more than minimum wage.”

Most arrests did not lead to charges and that would suggest the police had taken sides

by Professor Jim Phillips, senior lecturer in economic and social history

The miners’ strike in 1984 was a significant turning point in Scotland’s history, and that is one of the many reasons why we should be proud, as a country, to right the injustice so many suffered.

There is very limited confidence that the UK Government is at all interested in workers’ trade union rights in the here and now, never mind them revisiting injustices experienced by the miners almost 40 years ago.

We’ve got to do it here. We have our own parliament, and all the tools we need for Scotland to take the leading role and show the rest of Britain what should be done.

Indeed, the scope of the Miners’ Strike (Pardons) (Scotland) Bill should be expanded to include more miners who were arrested away from official picket lines and include an even wider range of offences than just breach of the peace, police obstruction or breach of bail.

Many miners were arrested in local communities, away from official picket lines or demonstrations. They should be included in any pardon. There shouldn’t be a hierarchy of justice.

Proportionately, Scotland suffered higher rates of arrests and convictions than other parts of the UK. Our miners were twice as likely to be arrested than miners in England, and three times more likely to be sacked.

They were arrested by police in Scotland and convicted in Scottish courts where our Sheriffs sentenced them. It’s only just that we do the right thing by them now.

Those who were sacked lost redundancy money and pensions which impacted on their future. They should be compensated.

Setting things right wouldn’t cost huge sums of money in the great scheme of things. But for those who suffered, it would mean everything.

It’s harder to measure the injustice many suffered after the strike, because of anti-trade union blacklists which hindered them getting jobs in the construction industry, in particular.

There is no doubt skullduggery went on, whoever was at the bottom of it. The miners and their families lost such a lot because of the way they were treated. They went from being the backbone of this country, to finding themselves stigmatised and facing an uncertain future. Some never recovered from what was done to them.

It should also be remembered that the closure of the mines wasn’t done to clean up industrial practices to save the planet. This wasn’t about any climate emergency, because those concerns didn’t exist in the 1980s. The whole thing was about money, tackling the unions and removing their power.

As many as 60% of arrests here did not lead to any criminal charge and that suggests the police and courts were not impartial guardians of justice but taking sides in a lawful industrial dispute between two parties, the miners and the National Coal Board.

The lasting effects of the Miners’ Strike led to attacks on other unionised workforces, and outcomes still felt today.

Very soon, we saw contacting out of public services, reduced wages and a huge shift in the balance of power both in society and workplaces, which is one reason so many are facing a cost of living crisis right now.

Righting the wrong done to those arrested in 1984 is an opportunity for Scotland not a burden, a chance to do the right thing.

We should take it.

Professor Jim Phillips is a senior lecturer on economic and social history at Glasgow University

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM