It has been a year of trials, errors and success, of two tentative steps forward and one hurried pace back.

Most of all, for our health professionals, our scientists and our political leaders it has been a year of discovery and of lessons learned the hardest, most heartbreakingly way imaginable.

Here, PETER SWINDON asks leading experts in their field to identify the most important lesson.

It’s not about blame but an accountability and a willingness to learn from mistakes.

Brian Wilson

Commentator

A year ago, we had just returned from holiday in Thailand where temperature screening in public places and wearing masks were the order of the day, without any sense of abnormality or panic.

Today, Thailand has had fewer than 100 deaths from Covid-19 in a population of 70 million. As with so much else, it is inescapable to wonder why it took so long to learn from what was already developing around the world.

When I say “we”, it doesn’t really matter if it is Scotland or the UK as a whole, for the outcomes are similar. With more than 9,000 deaths, an economy in paralysis and an unquantifiable toll of damage to education and mental health, it has been a litany of gloom. As always, the poor suffered most.

One error everyone should avoid is wisdom after the event – if you didn’t say it then, don’t say it now. On that basis, I can point to my view from the outset that this was an opportunity for Scotland to use our devolved powers in a distinctive way.

Long before the Scottish Parliament existed – since 1948 in fact – the NHS in Scotland has been devolved, with the right to do things differently. Not in competition with the rest of the UK, but in recognition of our own distinct geography and demography.

With a small population, we should have used these powers to stick with the World Health Organisation mantra of test, test, test. There were experts in the early days pleading for that approach and I don’t know why they were sidelined.

By early March, it was scarcely news that care homes were vulnerable. Shocking images from Madrid and Milan were there for all to see. It remains incomprehensible that patients here continued to be discharged from hospitals untested – or even when positive – into care homes. Time must not diminish the need for all that to be answered for.

The same goes for the Nike conference outbreak in Edinburgh which only became public knowledge months later. At that point, the Scottish Government should have put their hands up and admitted it was a huge mistake not to reveal the outbreak at the time, in which case there would undoubtedly have been an earlier lockdown throughout the UK, with many lives saved.

My take on that is that two weeks after the outbreak just along the road, I was in an Edinburgh pub with French rugby supporters. That should not have been possible and would not have happened if the significance of the outbreak had been made public.

No one should be interested in blame-fixing but we are entitled to expect accountability and, above all, lessons learned. That is the least we owe to the NHS and all who have been in the front line to protect us.

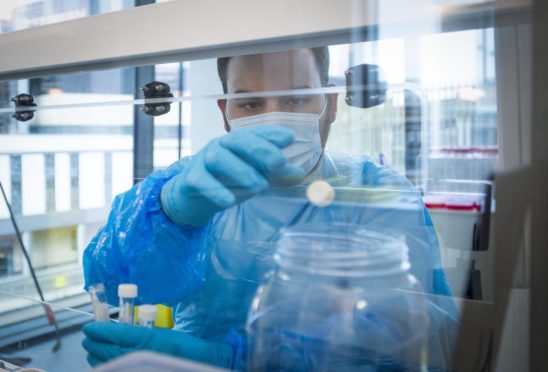

We must invest in our diagnostic labs and IT connectivity

Alan Wilson

President of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences

If we had a better diagnostics industry and testing infrastructure that had not been pared back we could have delivered testing at the beginning of the pandemic that might have allowed us to limit the deaths.

We just did not have the capacity to identify those that were positive to try to isolate them and stop the spread.

The comparison is with the investment in the pharmaceutical industry, which is well supported by government and other agencies.

If you look at what we have done with vaccinations, it’s because we have that pharma base. If we had a similar base for diagnostics then we would not have had the death rate we have experienced. This has also opened the lid on laboratories and testing. To the vast majority of people, we are just a little box where the sample goes in and results come out and no one really thinks about the complexities.

The other thing we’ve learned is the importance of connecting IT systems to get the results to the people who need to act on them.

We know the importance of that in the NHS but I don’t think the UK Government picked up on it and the Lighthouse lab did not link up IT at the beginning. We are getting that data now, now that politicians have learned the importance of IT in testing and diagnostics.

We must value our key workers

Roz Foyer

STUC General Secretary

Bad work kills. There are sectors where people are in precarious work with zero-hours contracts. They haven’t been able to self-isolate when they have shown symptoms of the virus.

They have had a terrible choice to make between putting food on the table or following government guidelines. We have no doubt this has helped spread the virus.

The pandemic has really shone a light on the problems in our labour market and magnified them. Our essential key workers – the majority of whom are women – have put themselves and their families at risk but are on poverty pay and their work has been undervalued. We need to make sure that those workers who carry out essential work are paid appropriately.

Another issue is statutory sick pay of less than £100 a week, one of the worst levels in the western world. People just cannot live on that so we are asking for it to be raised to £300 a week for those who don’t have a gold-plated employment contract.

We can’t ask people to comply with public safety measures if there is nothing to rely on for financial support.

Our care homes are designed to care, not control infection

Donald MacAskill

Scotland Care chief executive

One of the better pieces of learning is the understanding of the uniqueness of a care home environment compared to other environments when we are trying to control an infection.

A care home is essentially collective living; it is not an infection control unit. It is an environment where individuals, many living with the distress of dementia, cannot be easily isolated.

At times during the pandemic, we failed to get the balance right between infection control and care management.

How to do infection control during a pandemic is one of the biggest questions that has been raised and something we’re still learning about.

Also, we needed, and we still need, better integration between primary care health and social care.

At times during the pandemic, social care staff felt they were fighting a virus on their own. Whilst there was excellent collaborative working with palliative care and pharmacy colleagues, that was not the same with GPs. We need to get a lot better at general practice support for care homes.

Our hospitals need hundreds of beds

John Thomson

Vice-president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine Scotland

Pre-Covid, having a crowded emergency department was the norm. We’d have patients in cubicles and in the corridors waiting to be seen.

In the first wave the ability to move patients to a ward in a timely fashion – what we would call exit block – disappeared because all non-critical services stopped. Exit block is now back, despite the fact that we’re not back at pre-Covid numbers. This is because there is not enough capacity in the system.

Prior to Covid there weren’t enough beds and perversely, due to the need for physical distancing in wards, we have lost more beds. We’re not clear how many beds have been lost in Scotland but prior to Covid we were short of 639 beds. We’re probably short of around 1,000 now.

That has to be addressed because it has manifested itself in ambulance stacking – when ambulances are unable to transfer patients to the emergency department because patients can’t be put on trollies in corridors. Infection prevention and control means corridor care is no longer acceptable – and it never should have been.

At some hospitals, patients can now wait in the back of ambulances for hours.

We should never underestimate people’s desire to do the right thing

Stephen Reicher

Professor of social psychology at University of St Andrews

At the beginning it was feared the public would be the weak point in the pandemic.

However, we’ve seen extremely high levels of compliance with restrictions. In many ways the public has been our best resource.

So, there has been a change in the thinking about the public psychology as fragile.

In future, we would do far better starting from the presumption that people want to do the right thing, and think how to support them in the best possible way.

We could still do more. The first thing is to get people to self-isolate. Without self-isolation testing is pointless. Therefore, it’s a matter of offering practical support to self-isolate. That’s a key issue.

Secondly, the way in which we have been thinking about lockdown restrictions is unhelpful as lockdown implies people have done something wrong.

We should think more in terms of support measures in areas where there are outbreaks, so that people can endure restrictions.

There was controversy about local restrictions not because people were against them, but because they saw them as punitive and there wasn’t support to help them go along with them.

Scotland’s poor health made more people vulnerable

Linda Bauld

Professor of public health at University of Edinburgh

We had deprioritised and disinvested in public health for some time and we were just not ready for a pandemic.

In Scotland, public health is part of the NHS but it sits as departments. They are really quite small teams.

We did not have a contact tracing infrastructure ready to go. We did not recognise that we would need a testing infrastructure early enough.

We have deprioritised public health generally, compared to nice hospital equipment and hospital buildings.

We have also learned that we have a population that is vulnerable because of lots of chronic disease such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes.

There is speculation that one of the reasons the UK’s excess mortality is so high compared to our European neighbours is because of non-communicable diseases.

We just have poor health in this country, particularly in Scotland.

In future, communicable diseases such as Covid and non-communicable diseases need to be regarded as equally important.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM