Say the word cuckoo and it evokes the idea of temporary insanity or a fantasy land.

Now the bird that has inspired myth and metaphor is the subject of a new book.

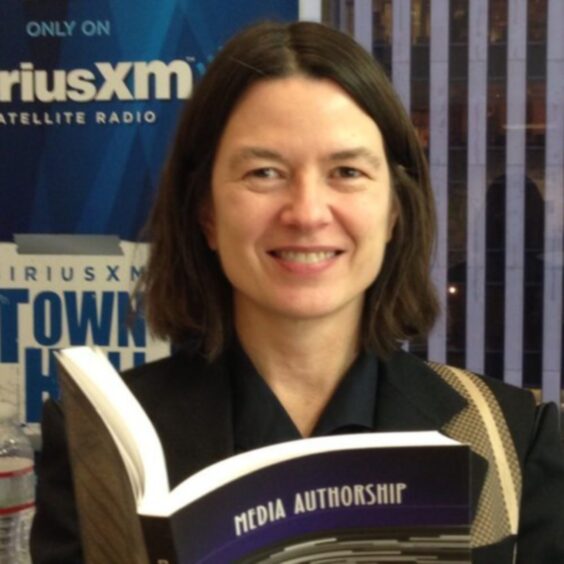

Here, author and media culture professor Cynthia Chris, tells Sally McDonald the all about the cuckoo.

Why was it important to write a book about the cuckoo?

In a world of escalating climate change, acidifying oceans, habitat loss, and other threats, I think it’s important to share animal histories and stories. The work of writers that I admire like Ed Yong, Lulu Miller, and Sabrina Imbler vibrate with joy at finding that we co-exist on this planet with beings that may seem so different from ourselves, but with whom we share an evolutionary history. Philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith and ornithologist Mark E Hauber have also written popular books that are scientifically rigorous but that also convey to readers the beauty and intelligence of non-human animal life.

The passion of these writers is contagious. If we can share our knowledge, and our sense of wonder, with others, that’s a good day’s work. And the cuckoo or “gow”’, as the bird is known in Scotland, seems a good fit for such work.

How long did the research take and where did it take you to?

I worked off and on for a couple of years. The most important “field trip” I undertook for this book was a delight: friends in a little village called Wivenhoe, in Essex, made sure I got to hear the famous two-note call of the male common cuckoo, which is a pretty frequent sound during their breeding season, though the birds themselves are notoriously very hard to spot. I also got to explore behind-the-scenes collections of some major natural history museums. Just as importantly, my research took me deep into the literature and other works of art where the cuckoo plays a role, from Aesop’s Fables to Ken Kesey’s harrowing novel One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, which was famously remade as a film by Miloš Forman.

The cuckoo seems to have a bad press, why?

You don’t have to dig far into the cultural history of the cuckoo to find its reproductive behaviours can alarm humans. Even Charles Darwin couldn’t help himself: he declared the cuckoo’s ways “strange and odious”. Some cuckoo species are brood parasites. They don’t pair up for more than the momentary act of mating; they don’t build nests, and — this is what seems to upset people — they don’t raise their own offspring.

In late spring, the common European cuckoo female lays her egg in the nest of another bird and goes on her way, laying prolifically, a dozen or more eggs each season, before heading back to wintering grounds in Central Africa. The host is typically a much smaller species, like warblers or pipits, birds that do pair bond, which is good news for the voracious baby cuckoo, who will have not one but two foster parents supplying it with food.

Meanwhile, because the cuckoo hatchling tosses its hosts’ eggs from the nest, the songbird loses an opportunity to raise its own young.

How has this impacted cultural media?

This curious behaviour has inspired many a myth and metaphor and has given us the figure of the “cuckold” who appears in literature of Scottish and English bards Robert Burns and Shakespeare, and in Ulysses by James Joyce to science-fiction thrillers. The cuckold is a man whose wife has strayed, impregnated by a man who is not her husband. It’s a humiliating role, often broadly comic.

The horror genre takes another angle, calling on the cuckoo to inspire tales of grotesque, mysterious pregnancies and preternaturally fast-growing babies forced on couples or individuals who have no intention of reproducing. The 1957 novel The Midwich Cuckoos, by John Wyndham, and its film adaptations under the title Village Of The Damned are classics, and more recent movies like Vivarium (2019) and Cuckoo (2024) reimagine these tropes.

How many varieties of cuckoo are there and where can they be found?

There are more than 140 different members of the family Cuculidae, which includes the couas, coucals, malkohas, anis, and guiras, to name a few. They are widely distributed – you can find some kind of cuckoo kin just about anywhere other than Antarctica. The book focuses mostly on the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus).

Have their numbers declined or grown in recent years?

The common cuckoo is still common, but there is cause for concern. Populations of some of the songbirds who are their favoured hosts are declining.

Climate change is making their migratory route more arduous, as it can be more difficult for them to find food for long stretches of the Sahara. Fortunately, groups like the British Trust for Ornithology are doing an amazing job gathering new knowledge about these birds. They tagged five birds on the banks of Loch Katrine for research. The organisation states that while cuckoo population is showing a long-term decline south of the border, in Scotland numbers have fluctuated but have shown overall stability since the start of the Breeding Bird Survey in the mid-1990s.

Cuckoo by Cynthia Chris is published by Reaktion Books.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe