On a hot and hazy summer’s day in August 1906, 13-year-old John Burdon Sanderson Haldane slipped on an ill-fitting diving suit, helmet and hefty metal boots, and dropped into the water off the coast of Rothesay.

Touching down on mud at 36 feet, the teenager plodded along the soft floor, ignoring the cold water trickling in through the gaps in his oversized outfit. He was hypothermic by the time he was wrenched back onto the HMS Spanker, but his larger-than-life father, John Scott Haldane, fed him a nip of whisky and the youngster soon warmed up.

Young Haldane’s dive came on the 10th and final day of intense and dangerous experiments as a small team of respiratory researchers – led by Haldane Sr – attempted to solve the mysteries of undersea survival through decompression science and gas physiology. The strides made in the waters off the west-coast seaside town were significant, so much so that John Scott Haldane was offered a knighthood for the work – a title he declined as he could see no practical use for it.

JBS Haldane, who had proved himself a scientific genius from a remarkably young age, carried on the research of his father in the years after, and it was for this reason he was to be found, more than 30 years later, awkwardly squeezed inside a steel tube 4ft in diameter, housed inside a cold warehouse in London as the Second World War raged in the city.

Looking to the sea

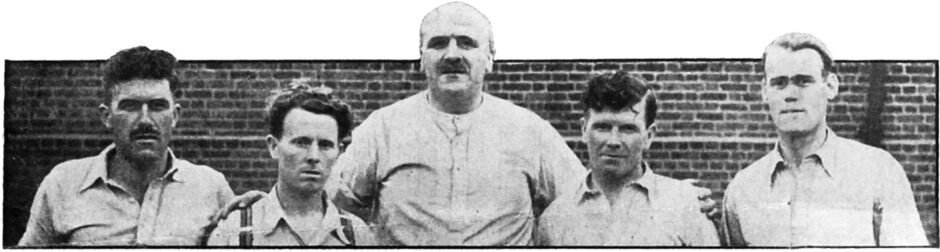

As the Blitz stormed above, it wasn’t to the skies where Haldane focused, but to the ocean depths. Alongside Dr Helen Spurway, he led a maverick team of scientists as they endured painful and potentially fatal experiments while fearlessly pioneering advances in underwater reconnaissance.

It was their discoveries that led to the safe use of miniature submarines and breathing apparatus that proved pivotal to the Allies taking the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Without their scientific breakthrough, the events of June 6, 1944, would not have played out as they did.

Released on the 80th anniversary of D-Day, a new book connects the lines between the science, the military manoeuvres, and the Haldanes for the first time. Chamber Divers is written by Dr Rachel Lance, a biomedical engineer at Duke University in North Carolina, who specialises in the physiology of human survival in extreme environments.

The relevant military records had been declassified long after the scientific records were released, so no one had taken the time to study and link the two. When Rachel began to dig into the files, she was surprised to find JBS Haldane was central to the story.

“It was a surprise to me how pivotal he had been,” she said. “It took me some time to figure out what he had been doing and what he was applying it to, even though I do this same type of science as a professional researcher. He was good at handling classified information so it wasn’t obvious what he was doing. Once I worked it out, I realised this was the book.

“As I read more and more of the government documents showing how the science was used, I discovered how key his lab work, which is kept at the National Library of Scotland, had been.”

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane was born in 1892 to John Scott Haldane, a famous scientist born in Edinburgh.

“John Scott Haldane lived there most of his adult life but eventually moved to Oxford with his wife Louisa to be a professor and it was there that JBS, who strongly identified as Scottish, was born,” Rachel explained. “JBS’ sister would later become a prolific Scottish novelist as Naomi Mitchison.

“They were a family of geniuses who had enough financial resources and enough social clout to do whatever they liked doing without much external suppression. For them, that meant science. The kids grew up doing all this crazy science in their home. I think a lot of it was facilitated by wealth and social stature because they were able to create their own world.”

Suffering for science

Carved into the stonework of the house was a family motto that would encapsulate what they were each willing to do for the sake of science: Suffer.

There were makeshift labs in the basement and attic. The siblings had 300 guinea pigs in cages, carrying out genetic testing on the rodents. At three years old, Haldane was a blood donor for his father’s experiments and a year later he was riding on the London underground with his dad collecting air samples in a jar. They discovered carbon monoxide levels so high that the council decided to electrify the lines.

He was still four when he was down the mines with Haldane Sr as the physician tried to make the air supplies safer for the workers. The use of canaries to detect dangerous gases was the idea of John Scott Haldane.

“One of the more famous stories is when JBS’ dad essentially tricked him into knocking himself unconscious in a mine that had been contaminated with unbreathable gas, so this was a family very open to self-experimentation and the idea that their bodies were one of the most accurate tools in an era before we had computers and sensors. Today, I would use a mass spectrometer for a lot of this stuff, linking everything to my data acquisition computer; they didn’t have that technology, so they were using the most reliable sensor they could think of, which was themselves,” Rachel explained.

During the First World War, Haldane Jr joined the Black Watch and found himself deep in the trenches. He would describe a month of non-stop bombing as one of the happiest months of his life and described the war itself as a very enjoyable experience, despite, as Lance notes in the book, being twice torn apart by shrapnel.

While John Scott Haldane was too old to be drafted, he contributed to the effort by addressing the toxic gases that had been choking soldiers in the trenches. He locked himself inside his home gas chamber with material designed to absorb carbon dioxide inside enclosed spaces like submarines to test its performance. He also asked for samples of the poisonous gases being used on the frontline, helping to identify chlorine as one of the gases.

Rachel continued: “JBS was teaching explosives on the frontline, but his father used his contacts to pull him from the trenches and put him in the gas chamber to expose him to chlorine gas. The family, including Louisa and Naomi, became collectively responsible for gas mask designs. It was the wildest life!”

That sense of selflessness is why Haldane found himself in the 4ft-diameter steel cylinder in 1942, pushing his body to the limits alongside other dedicated scientists. The need for their mission to succeed had been brought into sharp focus on August 19, 1942, when a storming of the beaches at Dieppe, France, ended in utter devastation for the Allied forces. The operation was woefully ill-prepared. In fact, the collective militaries’ only knowledge of the composition of the beaches came from a holiday photograph someone had taken years before. Tanks had been sent in a hope-for-the-best scenario that saw only a few of the 6,000 troops survive, with Canadians making up the bulk of the fatalities.

“So many people died because strategies were being used that we now know do not work,” Rachel said. “In the First World War, the strategy was usually to put more people on the front line. But, between the wars, you started to see things like advanced munitions and advanced ordnance. They no longer had to be good at aiming; they could just unleash hell, and that’s exactly what happened.

“It became clear the old strategies were no longer going to work, even if they were willing to sacrifice huge numbers of soldiers, so they had to rely on something new, and that’s what this lab group was working on. It was underwater stealth, underwater scouting. It gave them the ability to use intelligence instead of brute force.”

The experiments

Over 284 days, up to January 28, 1944, Haldane’s team conducted 611 experiments on themselves, with Haldane and Spurway participating in 438 of them.

“They were at risk from a lot of things, and they experienced almost all of them at some point,” Rachel explained. “They all had cases of decompression sickness, otherwise known as the bends. The most dangerous thing was the seizures, which looked different for each person.

“JBS had a massive seizure where he ended up partially conscious and broke a bone in his lower back. He registered for disability after the war and was considered disabled for the rest of his life – which ended in India in 1964, aged 72 – due to the ongoing back injury which never quite healed.

“When Spurway had a seizure, she tended to dislocate her jaw. There was one experiment where she dislocated it at least five times. The person in the chamber with her had a medical degree but had never practised medicine, so he had to figure out how to reset her jaw in this incredibly isolated environment.

“Another member of the group broke a bone in her thoracic vertebrae, which is the lower neck/upper back. She was at risk of paralysis during that injury, but thankfully it didn’t happen.”

To make the D-Day Landings successful, underwater warriors were required to place markers and beacons in advance, to know the positions of guns, the slopes of shores, the type of ground, and the locations of obstacles. The work of Haldane’s team helped to make this a reality.

“In my opinion, the resulting contrasts between the different beaches of D-Day can be traced at least in part to Haldane and this group,” Rachel said. “Omaha, one of the American beaches, was considered to be the worst because they essentially missed their landing target. As a result, they had many of the same things happen that happened at Dieppe. They were subject to a huge fire storm of munitions, which they had to overcome, and did. But the casualties were higher at Omaha than anywhere else.

“In contrast, Sword beach, while you can’t say the day went perfectly, it went comparatively smoothly, and they had the X-craft guiding them in. They had the divers out there quickly working on the underwater obstacles and working on the ordnance. They were immediately using this amphibious capability that came out of the ability to breathe underwater and they were using it a lot more diligently, and I think that’s responsible for some of the contrast in the outcome.”

Rachel will be in the UK this week to launch her book, which she dedicated to her grandfather, Earl Strawbridge Lance, who passed away while she was in high school. It was only after Rachel had earned her PhD in underwater explosives and was working with the US Navy that she discovered her grandpa had also worked in underwater explosives during the Second World War.

“His specialities were underwater explosives and rocket launchers – which is the coolest business card in history. He was one of those who couldn’t talk about his experiences in the war, so we didn’t know.

“I wanted to include the dedication in the book because he was one of the people who certainly would have benefited from the work that Haldane and his team did.

“I mixed together his military work with my memories of him, which weren’t as a war fighter but as an incredibly kind man who took care of me, as I wanted to make the point that D-Day did not happen because of these scientists, but that more people – like my grandfather – got to come home and live entire lives because of these scientists.”

Chamber Divers: The Untold Story Of The D-Day Scientists Who Changed Special Operations Forever by Rachel Lance is published on Thursday by Bedford Square

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Shutterstock / Everett Collection

© Shutterstock / Everett Collection © The National Archives

© The National Archives