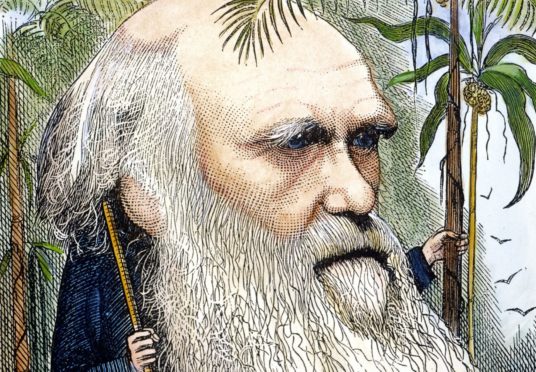

As one of the world’s most celebrated scientists, Charles Darwin no doubt knew the value of a second opinion.

So, when the father of evolution was struck down by a mystery stomach disorder at the height of his fame he sought an expert perspective.

Now researchers have discovered how Darwin turned to brilliant Scots anatomist John Goodsir in his search for a cure – and how Goodsir suggested he try creosote.

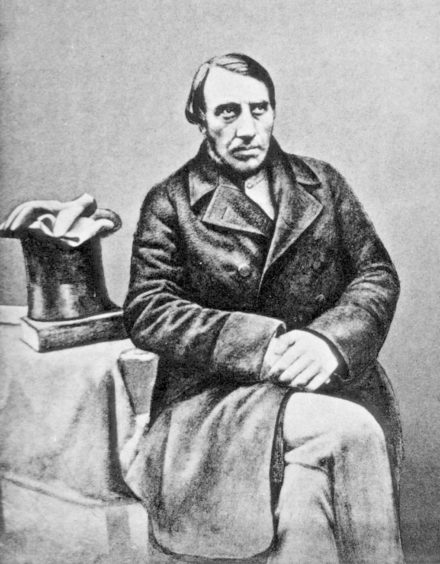

As well as Darwin’s desperate quest for good health it throws new light on the relatively unknown Goodsir.

Professor Ken Donaldson, senior research fellow at Surgeons’ Hall Museums, Edinburgh, discovered the correspondence when undertaking other research.

He said: “I’m very interested in Darwin and evolution and this conversation between these two great men, Goodsir and Darwin, is a dream for someone doing this kind of research.” Professor Donaldson’s research, published online by the Scottish Medical Journal, tells how in 1842 Goodsir published a paper that was“remarkable for its prescience and attracted the attention of Charles Darwin”.

Goodsir described a 19-year-old man who had suffered a stomach complaint for four months. He discovered what is now known as a bacterium (which he believed to be a plant) which he named Sarcina ventriculi and considered it the cause of the teenager’s illness. Goodsir prescribed creosote, then used to treat tuberculosis and pneumonia, later declaring it a “complete success”.

Darwin set out his famous theory of evolution in his work On The Origin Of Species in 1859, based on insights gained during his time on HMS Beagle. It profoundly changed the understanding of human life.

The paper said: “On returning from the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin suffered severe and ongoing health problems that plagued him for the rest of his life.

“[Darwin] read Goodsir’s paper and contacted him and asked if he could send some vomitus samples to Edinburgh in the hope Goodsir might find Sarcina in it and solve the mystery of his debilitating stomach symptoms and perhaps cure them.”

Goodsir agreed, adding: “If your medical adviser has no objection, you might try creosote.”

It’s unclear whether Darwin actually took the creosote but Goodsir subsequently found no trace of Sarcina, a type of bacteria, and Darwin’s ill-health continued.

Prof Donaldson believes Goodsir “can arguably be considered amongst the first to link a specific micro-organism with a disease” – decades before celebrated microbiologists Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. He said: “At that time, people suffered all sort of strange diseases and sicknesses and vomiting, but nobody thought to pin it down to any particular thing. The golden age of microbiology, when all that was put together, was the late-1800s and we’re talking here about really 1840.

“Goodsir was decades ahead of his time in doing that and actually treating it. It wasn’t as subtle as an antibiotic, creosote; it might sound pretty awful but it was really just two or three drops in a volume of water. Of course, if the bug grows in your stomach and you put the creosote into your stomach it will certainly kill the bug.

“Goodsir was a brilliant teacher and a brilliant anatomist but he didn’t churn out papers that might have got him much more widespread recognition. Who knows what he might have got to if he’d not decided to confine himself pretty much to teaching?

“It was an amazing concatenation of ideas between discovering it, treating it and then Darwin contacting him. Such a great story.”

Goodsir was born in Fife and went to St Andrews University at just 13. Just three years later he was apprenticed to the surgeon Robert Nasmyth, who was Queen Victoria’s official dentist in Scotland.

He was held in such high esteem by his peers that Rudolf Virchow, dubbed the father of modern pathology, dedicated the English language edition of his ground-breaking book Cellular Pathology to Goodsir.

Darwin, himself, had significant links with Scotland, going to the University of Edinburgh, aged 16, to study medicine. Although he didn’t complete his degree, he helped the marine biologist and sponge expert Robert Grant in his studies of marine life on the Firth of Forth.

Darwin returned to Scotland in 1838 for a three-week field trip to Glen Roy’s “parallel roads”, markings on the hills left by Ice Age lochs. He said: “Here I enjoyed five days of the most beautiful weather, with gorgeous sunsets, and all nature looking as happy, as I felt.

“I wandered over the mountains in all directions and examined that most extraordinary district. I think without any exception, not even the first volcanic island, the first elevated beach, or the passage of the Cordillera, was so interesting to me, as this week. It is far the most remarkable area I ever examined.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe