ALTHOUGH most of us are only too grateful for the chance to vote in political elections, millions still pass up on the opportunity to have a say in how our country is run.

This choice has a huge knock-on effect in determining the outcome of the polls.

The fact that so many of us skip our votes would have the suffragettes spinning in their graves.

They, of course, fought for women to be given the right to vote, and would be horrified that some people don’t seize the opportunity to do so.

It was 100 years ago that women were given the right to vote for the first time — albeit dependent on them having to fulfil certain criteria, such as being older than 30 and being a property owner, or married to one.

Whatever people’s reasons for not using their vote — and there are several — it was not a freedom that was always afforded to us.

In the 18th century, it was thought that women did not need their vote.

The assumption was — as it had always been — that their husbands would take any political responsibility, so there was simply no need for women to be politically engaged and vote.

While many women were to resent this point of view, by and large, the woman’s place was seen to be in the home, cooking for the husband and rearing any children they might have together.

The industrial revolution was set to change this way of thinking, however, when circumstances saw many women working full-time.

At their place of work, women were able to discuss politics and any social issues of the day with the other female workers, and this increased women’s desire to have a voice to influence the way in which the country was being run.

By 1866, females were beginning to campaign for women’s suffrage, and they were able to vote in local elections within a couple of years.

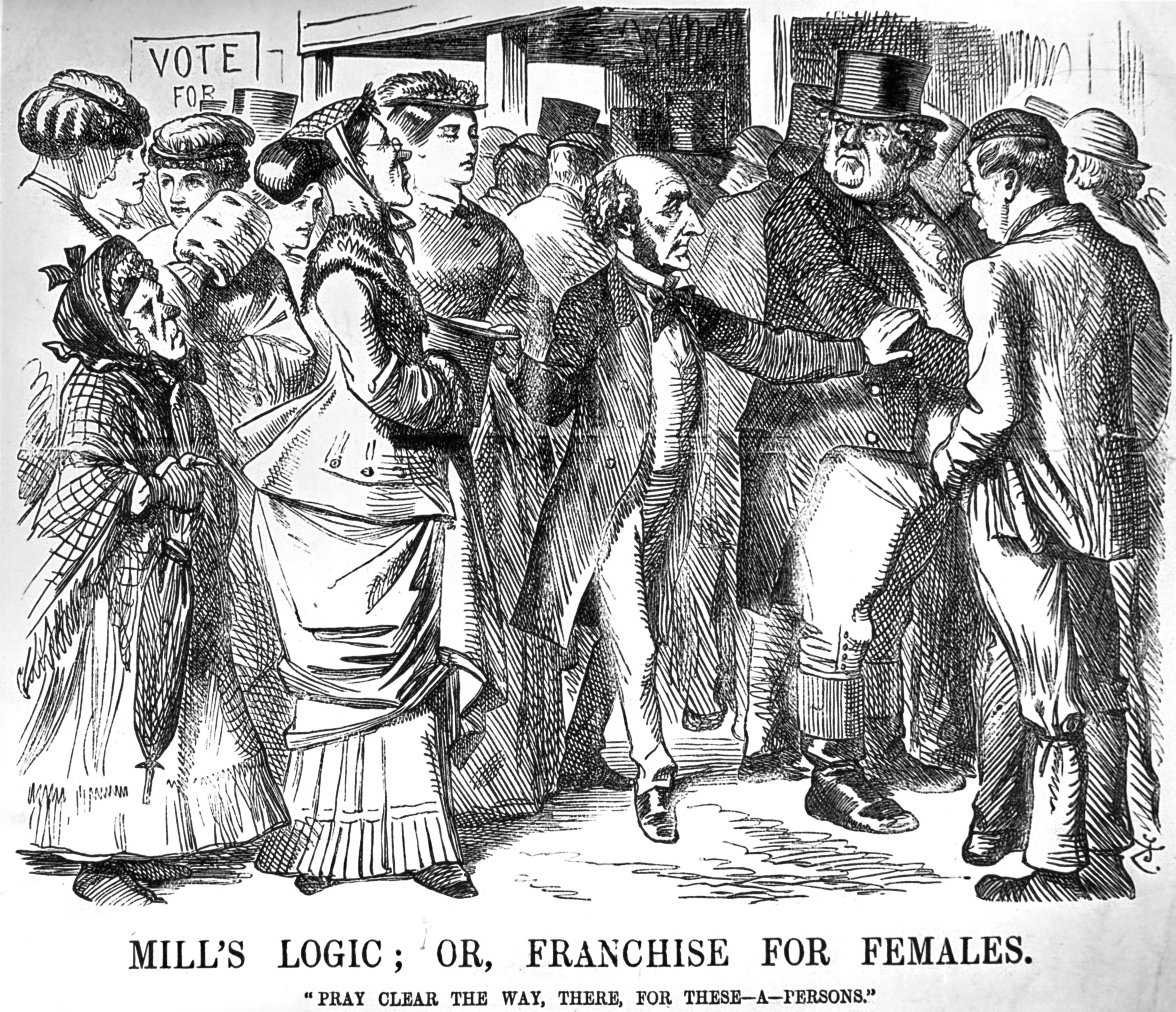

In 1867, John Stuart Mill proposed an amendment which would give women the same voting terms as men, but it was rejected by 194 to 73 votes.

As a result, the campaign for equality picked up pace.

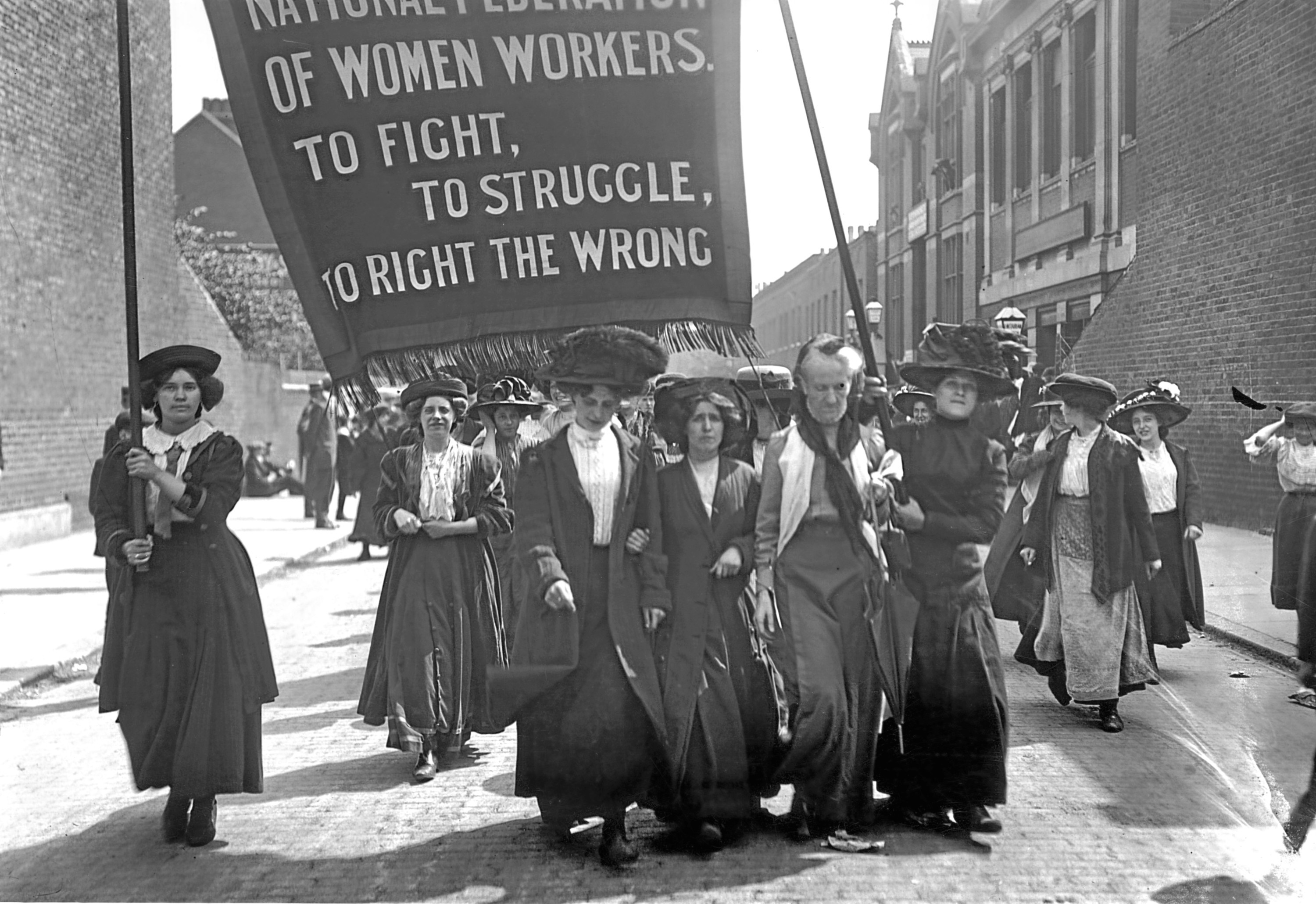

There were two wings involved in this struggle — suffragists and suffragettes.

The former’s origins can be traced back to the mid-19th century, while the suffragette movement began in 1903.

In 1897, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed by Millicent Fawcett, who wanted to win the vote by using non-militant tactics — non-violent demonstrations, petitions and lobbying of MPs were the kinds of things she had in mind.

As Millicent reasoned, if a group of people could present themselves as intelligent, polite and law-abiding citizens, the chances of their being successful were increased.

By 1900, many MPs were coming around to the suffragists’ way of thinking, and several bills in favour of women’s suffrage were very well supported, though not passed.

By the time 1903 arrived, frustrated at the lack of change in Government, one suffragist, Emmeline Pankhurst, decided more-forceful methods were required, and broke away from the middle-class respectable group she had formerly been involved with to create the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) or the suffragettes.

While the suffragists erred on the side of caution, Emmeline decided that actions speak louder than words, leading to the WSPU’s motto of “Deeds not words”, and young working-class women of the group resorted to violence and even hunger strikes to get their point across.

On July 5, 1909, imprisoned suffragette Marion Wallace Dunlop went on hunger strike in Holloway Prison as a protest against the authorities refusing to see her as a political prisoner — inmates of this category were supposed to be entitled to more “luxuries” than others.

According to Marion, the hunger strike was: “A matter of principle, not only for my own sake, but for the sake of others who may come after me . . . refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

She was released three days later, but when she inspired other suffragettes to do the same, it led to the introduction of forcible feeding.

This cruel tactic was initially branded as “ordinary hospital treatment”, to prevent the suffragettes from dying of hunger.

In reality, though, it was life threatening and was carried out by holding the prisoner down on a bed or tying them to a chair which would then be tipped back.

A rubber tube would then be forced either up the nose or down the throat and into the stomach.

When the throat method was opted for, a steel gap would be opened up, once in place, as widely as possible, causing extreme amounts of pain, tearing the tissue in the nose and throat.

There were also occasions where the tube was accidentally put into the windpipe, leading to food entering the lungs, and putting the prisoners at risk of death.

Some suffragettes were forcibly fed more than 200 times.

And so began the Cat and Mouse Act of 1913, which saw hunger-striking suffragettes released from prison to recuperate, to be rearrested later when they were healthy enough again for prison.

This would often drag out the prison sentence longer, due to the stop-start nature of the prisoners’ routine.

Forcible feeding was stopped in 1914 at the outbreak of the Great War when the WSPU called a suspension to violent forms of protest — arguing that the world had bigger issues to contend with — and the Government granted an amnesty to all suffrage prisoners.

It seemed that not even all suffragettes could agree on their methods that they should use, however, with Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel having broken away from the group in 1907 to form the Women’s Freedom League.

Though the various women’s rights groups may have disagreed in their approach to the problem, their end goal was the same, and the public supported the suffragettes, taking pity on them being subjected to such barbaric treatment in prison.

Some women — notably Emily Davison, who was trampled by King George V’s horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby — died for their cause.

There was a shift for the better in 1918 with the implementation of the Representation of the People Act, yet this still did not put women on an equal footing as men.

The act was mainly required to resolve the issue of soldiers returning from the Great War who were not entitled to vote as they didn’t meet existing property qualifications.

The upshot of the act was that all property qualifications for men over 21 were abolished, and women over 30 were entitled to vote — provided they met minimum property qualifications or were married to a man who did.

The age difference between male and female voters was to prevent women from becoming the majority voters, and after the act was passed, women made up 43% of voters.

It wasn’t until July 2, 1928, that the Second Representation of the People Act was passed into law.

This time, women were, at long last, given the same rights as men.

Tragically, Emmeline Pankhurst died just 18 days before full suffrage for women was granted, and never survived to see her vision come true.

These days, many people — male and female — still don’t use their chance to vote.

Perhaps were these people to live in the days before it was a standard entitlement, they would be use their privilege.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe