Locked down in London, author Shelley Klein escapes to the country every day – but only in her memory as she remembers growing up in one of Scotland’s most iconic homes.

She retreats in her imagination, to the Borders home where she grew up, nicknamed The See-Through House because of its open-plan design, lack of doors and glass panels set against a forest of trees.

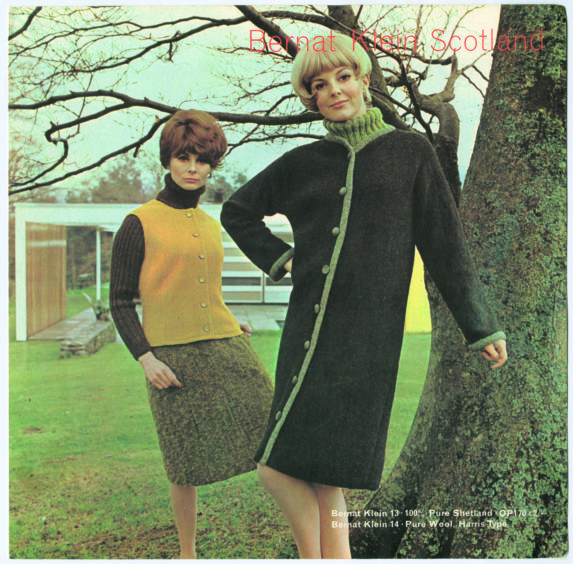

It was the vision of Shelley’s father, Bernat Klein, an acclaimed textile designer whose colourful creations were among the 60s and 70s must-have outfits.

The house named High Sunderland was built in Selkirk in 1957 for Bernat, a Yugoslav Jew whose mother was murdered in Auschwitz, and who – with a textiles factory in Galashiels – was to win a glittering array of fans including Coco Chanel, Yves St Laurent and Christian Dior.

The dream home Klein designed with architect Peter Womersley is lauded as one of Britain’s most iconic homes of the mid-20th Century, holding a rare Historic Environment Scotland Category A listing. But to the daughter who cared for Bernat in the last years of his life, it means much more.

Her memoir The See-Through House – out this week – is a touching and funny account of their lives in a “glasshouse” and a piercing portrait of the grief that followed his death in 2014, aged 91.

Shelley told The Sunday Post: “The house really was my dad. He put all his fabrics into the interior; the curtains, the upholstery fabrics, rugs, cushions. In my mind, I cannot separate the two. I don’t think I will ever get over having to sell it after his death. It is so full of memories. It was like losing part of myself, and my parents.

“There is not a day goes past where I am not ‘in’ the house. I walk through it in my mind. I can even remember inside the cupboards, the smells, the textures and the sounds. It is a very strong sense of being there and one that is at once comforting and painful.”

Klein transformed British textiles between the 1950s and 1990s and was worn by celebrities and royals like actress and model Jean Shrimpton and the late Princess Margaret. His numerous awards included a CBE and an honorary membership of The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland. RIAS secretary Neil Baxter said after his death that owning a Klein creation was “for a generation of Scottish women… an aspiration”.

Shelley, who was born in the house in the same month Coco Chanel featured her father’s mohair tweed in her spring 1963 collection, said: “What I tried to get over in the book was how a boy from a traditional Jewish background in a small town in northern Yugoslavia came to build a modernist house in Scotland.

“My father studied in Jerusalem during the war, and he came across quite a few modernist buildings there that really inspired him.”

But it was after leaving Leeds University where he studied textile design and met his wife Peggy, that he relocated to Scotland, eventually stumbling on the talent that was Womersley.

“My mum and dad were driving to Yorkshire on holiday when they came on a house designed by Peter for his brother. They stopped and knocked on the door.”

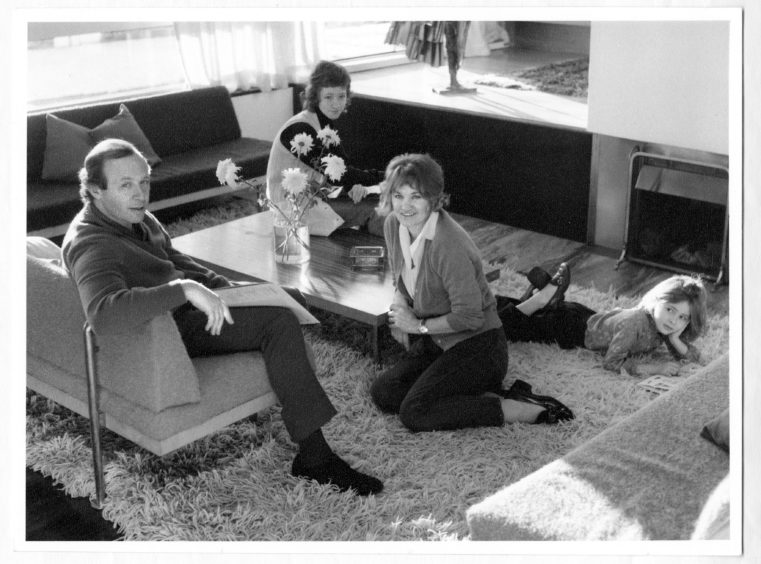

High Sunderland became Womersley’s first real commission. “It was a meeting of minds,” said Shelley. “Part of the remit was that dad could entertain business clients there, so the sitting room was sunk below the rest of the house with a walkway round three sides. All the big fashion editors would come up from London and sit in the sunken living room while models would walk round them wearing dad’s designs.

“As a very small child I would be allowed to peak from around the corner and could try the models’ wigs in the bathroom. It was fun but normal.”

Shelley, 57, who has an older brother and sister, added: “My mother created the knitted garments for dad and we all wore dad’s designs.

“When I got older I was much more inclined to wear Laura Ashley which my father was most distressed about. My sister would waft around in long floaty cheesecloth dresses and he would roll his eyes in despair. Growing up my friends’ houses seemed far more interesting to me than this glasshouse. There was nowhere to have a private phone conversation. I was a stroppy teenager but my bedroom didn’t have a door. I didn’t have anything to slam until I insisted my parents put one in.”

Shelley moved back to High Sunderland after her mum’s death in 2008. “Dad was getting very lonely and he missed my mother a lot – they had been married over 60 years,” she said. “He would never have survived going into a home. It would have been cruel to separate him from the house.

“We talked quite a bit about his own mother who died in Auschwitz. He adored her and told me how he used to love watching her brush her hair. His father survived – just. His younger brother also survived but there were lots of aunts, uncles and cousins all murdered. My father’s stoicism was extraordinary. He had a very strong sense of wanting to look forward never back. He painted up until the week he died from a heart attack. Almost immediately after, I wanted to get the house down on paper. It was a way of keeping close to my parents.

“I have a huge soft spot now for modernist buildings. They make me feel comfortable in a way that no other architecture does. I hate to say I live in a Victorian block of flats, but I have taken a lot of things from High Sunderland. My father’s paintings hang on the walls.”

The See-Through House by Shelley Klein, published by Chatto & Windus, is available now on Waterstones.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe