They were the so-called “painted people” and scourge of the Roman Empire who ruled Scotland over 2,000 years ago. However, it is only in the last 10 that archaeologists have understood the Picts.

Far from the semi-naked, tattooed, barbaric warrior tribes described by the Romans, leading experts now believe the Picts were sophisticated, traded with Europe, lived in large settlements and eventually laid the foundations for the kingdom of Alba and, eventually, Scotland.

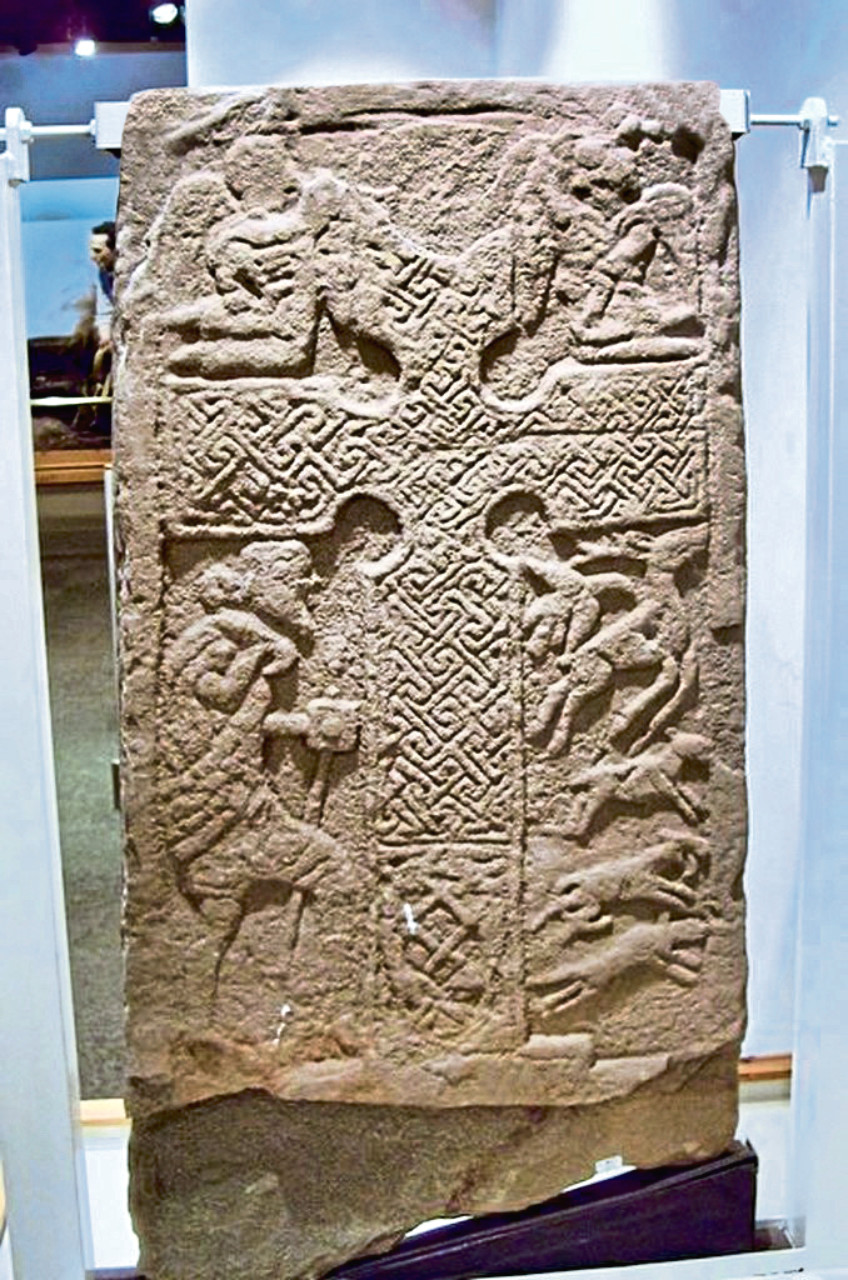

For years, the only historical evidence of the people who lived across northern Scotland from 300AD to 900AD were carved Pictish standing stones and a list of kings.

Now, with every pottery sherd, metal pin or bone fragment unearthed, a team of archaeologists led by the University of Aberdeen’s Gordon Noble are slowly piecing together how the Picts lived and ruled across Scotland.

“There is very limited historical information on the Picts so anything new that we find has come from the ground but one of the big mysteries has been the lack of archaeological sites from that period,” he said.

The Northern Picts project, led by Noble, has investigated a series of Pictish sites in northern Scotland most recently at Burghead on the Moray coast and Dunnicaer near Dunnottar Castle.

Yet it was starting at Rhynie, near Aberdeen, in 2011 that led to their first big breakthrough. A number of Pictish stones found around Rhynie village, including the standing Craw Stane and the famous Rhynie Man stone carved with a bearded man wielding an axe unearthed by a farmer in 1978, suggested the area was significant to the Picts. It turned out to be a royal epicentre that revealed the sophistication and scale of early Pictish society.

“The name Rhynie comes from an early Celtic word ‘rig’ for ‘king’ but it was only when we began excavating we found it was an extremely high status site for the time period of the 4th to 6th Century,” said Noble.

“We found materials suggesting elite status, such as very unusual imports from the Mediterranean, elite glass and pottery vessels and fine metalwork being produced at the site. At sites like Rhynie and Burghead, we found bronze and silver pins and brooches that also conferred wealth and status. These were made on-site, suggesting these were economic centres as well as power centres.”

He added: “We found sherds of pottery from amphora (vessels used primarily for storing wine), from the Mediterranean in the 5th and 6th Century, which were also found in other royal centres in Ireland and Britain. This suggests the Picts were well-connected over great distances and interacted with a much wider society.”

The later discovery of the hill fort Tap O’ North cemented the idea that the area was a large power base during the 4th to 6th Century. “The discovery of Tap O’ North, a large hill fort of the same period overlooking Rhynie, also suggests the scale of the Pictish society and what they were able to build,” added Noble. “It had 800 house platforms and is the second- largest hill fort in Scotland.

“There were probably many power centres in that period but Rhynie seems to be important as there are several high-status sites in that valley that could form one community.”

Another indicator to the wealth of the Picts is the St Ninian’s Isle treasure, discovered in Shetland in 1958, which included 28 silver and silver-gilt objects including broaches, feasting bowls and sword hilts. The items date to the 8th Century, suggesting they are Pictish, made in north-east Scotland, and may have been the accumulated wealth of a high-status family. Noble’s new book, Picts: Scourge Of Rome, Rulers Of The North, written with historian Nicholas Evans, who has researched Pictland through the University of Aberdeen’s Comparative Kingship project, explains how archaeology is helping paint a more accurate picture.

“As far as we know, the extent of the kingdom stretches all the way from modern day Fife up to the Shetland Isles and across the Western Isles, so it was a very extensive kingdom, which in itself was quite unusual for the time period,” he said.

“We’re now trying to identify more sites over that time period across Scotland, extending into Fife and Perthshire, which would have been home to southern Picts, to get a wider view of Pictish society.”

Further finds have also shed light on the significance of the enigmatic Pictish carved stones, 200 of which have been found across eastern and northern Scotland.

“At Rhynie we’re finding objects in the ground that look like the symbols or carvings you see on the Pictish stones,” said Noble.

“There are metalworking moulds for making little animal figurines that look just like the animals you see carved on the stones. We also found a little miniature axe pin for attaching clothing, that looks just like the axe that the Rhynie Man carries. It’s bringing the world of the Pictish stones to life, which is exciting.”

Pictish stones found across Scotland bear symbols depicting animals, people and warriors, or gods, sometimes mounted on horseback, objects like mirrors and combs, hammers, tongs and anvils and other abstract symbols.

Noble added: “Later stones have people carved on them next to symbols, suggesting it says something about that person, whether it’s their rank, or their name. You often get symbols in pairs that seem to work together.”

The name Picts comes from the Latin word picti, which means “painted,” since it’s believed from Roman sources that the Picts were either tattooed or painted their bodies for battle, yet there is no evidence this was the case.

However, Pictish imagery and unearthed fabric hints to how the Picts, who spoke Brittonic and initially worshipped Pagan gods before the introduction of Christianity in the 7th Century, dressed and lived. “We’ve found beautiful bone pins and bone combs at Burghead, leather shoes from Dundurn Hill Fort in Perthshire and a woollen shawl found in a bog on Orkney,” said Noble.

“Detailed carvings on the Pictish stones also show how people dressed in tunics with brooches and shoes and also the animals they kept, horses they rode and weaponry they used.”

Finds at Dunnicaer, a towering sea stack south of Aberdeen where a series of Pictish stones were found in the 19th Century, and other hill forts confirm Pictish clashes with the Romans.

“Places like Tap O’ North and Dunnicaer, which date third and fourth centuries have lots of Roman finds, whether that was booty from raiding or bribes from the Romans to buy off the natives to not cause havoc,” said Noble.

“The Picts resisted the Romans and even launched major attacks in Roman-occupied areas south of Pictland. They were a noted enemy of Rome in various Imperial sources, which gave them their Picti, painted people in Latin, nickname, which stuck.”

Unlike the Vikings, the Picts seem to have made less fanfare when burying their dead. Few objects have been found in Pictish graves, but Noble says the people marked their burials with barrows, raised mounds of soil or stone cairns, and later larger cists, a stone-built coffin-like box. Cairns could signify important burials, and female remains buried in such a way might also suggest women had some important standing within Pictish communities.

“We’re lacking historical sources we have uncovered a lot of female burials, which certainly suggests they had some status in society and, presumably, they were taking up some sort of leadership roles,” said Noble.

One of the big mysteries of the Picts is that they seem to vanish around 900AD, coinciding with the arrival of the Vikings. Yet, rather than being wiped out by Norse armies, Noble suggests the Picts’ disappearance was more nuanced and gradual as they assimilated into a new culture and power structures.

He said: “The Romans first mention them in the late third century and then they go on to become the most powerful kingdoms of Northern Britain. But in the 9th Century, early 10th they disappear from historical sources when they seem to merge with the Scots to create the Gaelic kingdom of Alba, essentially the forerunner of the kingdom of Scotland.

“The real political focus of Alba is in the Pictish territories, particularly Fife, Perthshire and Angus, which was the southern Pictish kingdom and cultural centre. It’s essentially the same polity with new leaders, so the Pictish kingdom essentially laid the foundations of Alba and later, Scotland, so they’re responsible for that process of nation building.”

Noble is determined to keep digging for more information.

He said. “On of the mysterious elements of the Picts has been the lack of archaeological sites. We’ve had success targeting sites where there are symbol stones, like Rhynie and Dunnicaer. Others have been pure luck, like Tap O’North, which was looking at other potential sites in the landscape near Rhynie.

“We didn’t think it would be from the same date so it was a huge surprise when carbon dating placed the fort in the Pictish period.

“We know the Picts lived across a large area of Northern Scotland so, through the Northern Picts project, we just need to keep trying to find new sites to dig into that time period and investigate on a big scale and understand more.”

Picts: Scourge Of Rome, Rulers Of The North is published by Birlinn, out now.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Cloud Nine/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Cloud Nine/Kobal/Shutterstock © Picasa 2.0

© Picasa 2.0