A Windrush victim has revealed his compensation – less than £3,000 for every year he was forced to wage a crushing, unsettling battle to stay in the UK where he has lived for 40 years.

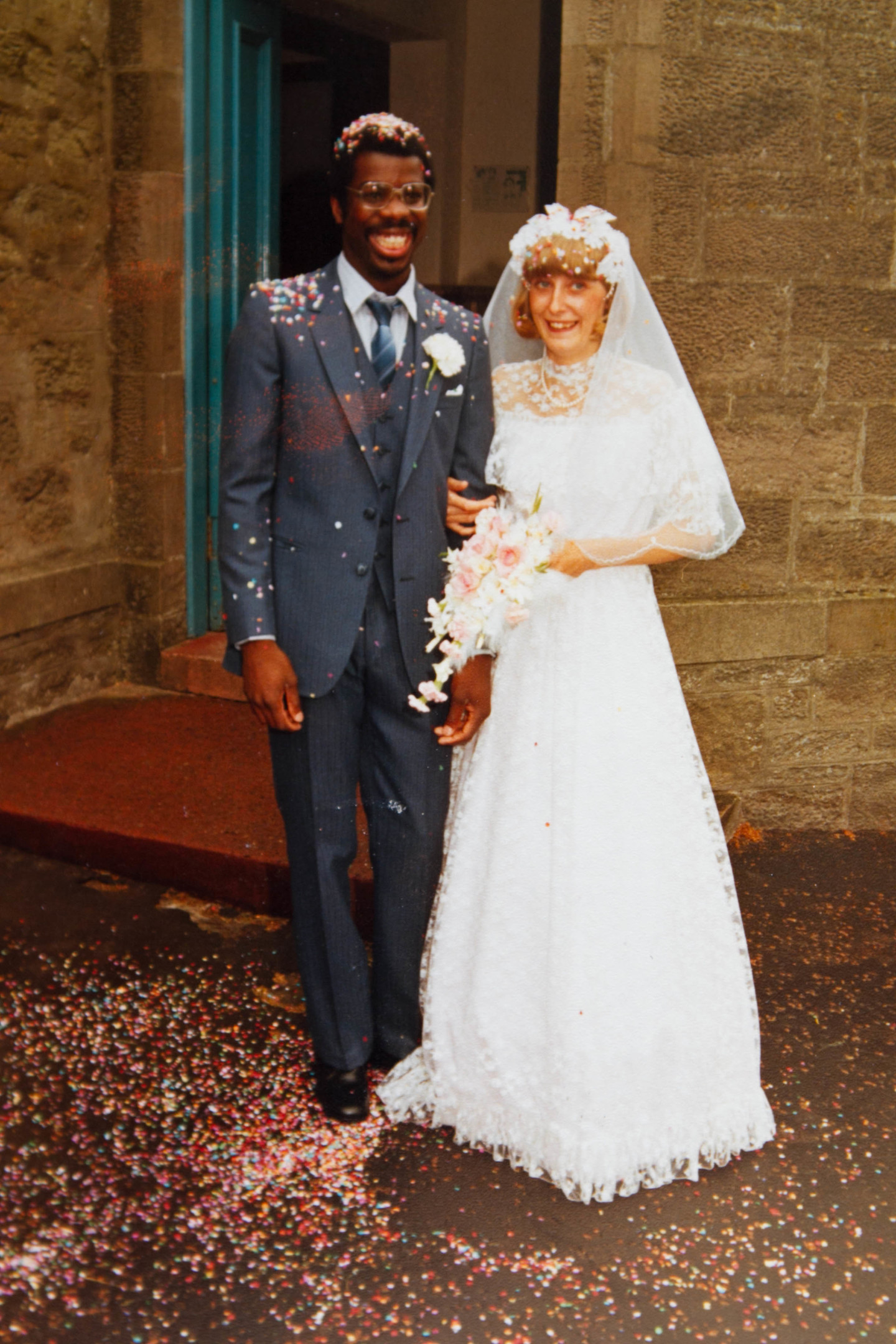

Paul Cudjoe, 65, originally from Grenada but settled in Dundee for four decades, says he has reluctantly accepted the £20,000 payment because he could not spend more years fighting for justice.

Cudjoe, who arrived in Britain as a schoolboy in the 1960s, was suddenly asked by the UK Government to prove he had the right to stay here under a policy designed to create a “hostile environment” for migrants.

The scandal exposed in 2018 involved men and women from the Caribbean who arrived in the UK in the 1950s and 60s being threatened with deportation. Many were members of the Windrush generation, named after the ship that brought one of the first groups of West Indian migrants to the UK in 1948.

Cudjoe and wife Frances were on a Caribbean cruise to celebrate their wedding anniversary in 2010 – the first time he had left the UK – when he heard his status was under official scrutiny and the dad of two was initially refused entry back to the UK.

That began a seven-year legal battle to prove he had the right to live here, during which time Cudjoe ran up lawyers’ bills of more than £3,000. His uncertain immigration status also meant he was unable to find work after being made redundant from his job with a demolition firm.

A compensation scheme was unveiled in 2019 and in December the Home Office announced a fast-tracked programme, with awards of between £10,000 and £100,000. Higher awards can be made in exceptional circumstances.

Cudjoe said: “I had to spend thousands on solicitors’ fees and lost job opportunities because I could not prove I had the right to stay in the UK.

“A good deal of my redundancy went on legal fees and my wife and children were upset and crying at the thought of me being deported back to Grenada, 7,000 miles away.

“Frances thought £20,000 was not enough considering all we had been through but we have to get on with our lives and, at 65, enjoy our lives.

“I worked for years in hard jobs, brought up two children and contributed to society. Being a hard-working family man was all I knew so I don’t know why I had to prove my place in society here. Others have not been so fortunate, been deported and died away from their families and I feel so sorry for them.”

Last month it emerged concern about how few people were applying to the Windrush compensation scheme had prompted eight leading law firms to join forces to offer free legal advice to applicants.

As of last month – two years after the scheme’s launch – only 1,996 claims had been made. Official estimates indicated more than 12,000 people may be eligible.

Originally, the UK Government estimated payouts would total between £200m and £500m. However, in November it emerged that fewer than five people had been awarded the maximum compensation figure, while by February just £6m had been paid to victims.

The Home Office said: “We are determined to right the wrongs of the Windrush generation and make sure they get the compensation they deserve for the injustices they faced. In December, we reformed the Windrush Compensation Scheme to ensure people received significantly more money more quickly and since April 2019 almost £18 million has been offered.

“Within six weeks of making the changes in December we had offered more than we had in the first 19 months of the scheme – since then, we have more than doubled the amount of compensation paid.”

It said 409 people had now received a payment with a further 703 people referred to the independent claimant assistance provider. The scheme has been extended to 2023 to allow people more time to claim.

The scandal

The Windrush scandal mainly affected UK citizens originally from the Caribbean.

Granted indefinite leave to remain in 1971, thousands were children who had travelled on their parents’ passports, so many were unable to prove they had the right to live in the country when “hostile environment” immigration policies – demanding the showing of documentation – began in 2012.

The Home Office kept no record of those granted leave to remain and issued no paperwork, making it hard for arrivals to prove they had a right to be in the UK.

In 2010, the Home Office destroyed landing cards belonging to Windrush migrants. People who lacked documents were told they needed evidence to continue working, get NHS treatment, or even to remain in the UK.

Changes to immigration law by successive governments left people fearful about their status and threatened with deportation. A review of historical cases found that at least 83 individuals who had arrived before 1973 had been removed from the country.

The name “Windrush” refers to the ship MV Empire Windrush, which docked in Tilbury in 1948, bringing workers from the Caribbean to help fill post-war labour shortages.

The influx ended with the 1971 Immigration Act, when Commonwealth citizens in the UK were given indefinite leave to remain. After this, an overseas-born British passport holder could only settle with a work permit and proof of a parent or grandparent being born in the UK.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© PA

© PA