Trying to gesture with what remains of her arms, the woman, a mother of six, tries to describe what caused such terrible injuries: her husband shooting her with a shotgun.

Across the city, a former TV news reporter struggles to hold up her head, falters over simple words and weeps every time she sees a mother and child on television.

Just two of the women filmed by producer Sinead Kirwan and her team after they began investigating femicide in Turkey for new film Dying To Divorce. They were left stunned by the women they met, the horrors they’d survived, and their determination to win justice.

The issue of domestic violence in Turkey has reached crisis point, with spiralling numbers and lenient sentences for perpetrators leading to mass protests and campaigns against a system women say is failing victims.

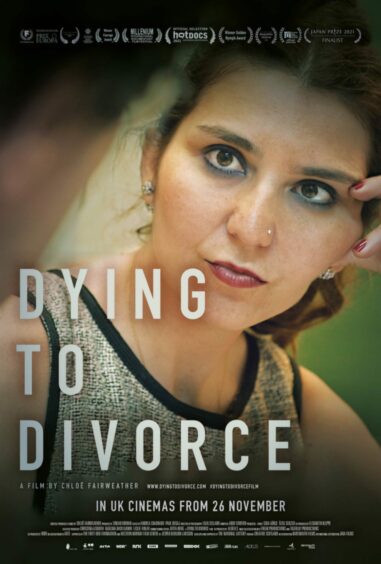

Kirwan and director Chloe Fairweather spent five years making the film – which has just become the UK’s official entry in the foreign features category at the Oscars – inspired by the survivor stories like that of mum-of-six Arzu.

When she asked her cheating husband for a divorce, he blasted her legs with a shotgun at close range, then fired at her arms because he wanted to make her “crawl” and leave her unable to hold her children.

Kirwan said: “The first person the team met was Arzu and were just so amazed at her dignity and her determination, in the face of very extreme violence, to just get on with her life. She really, really wanted the world to know her story.

“She is the most amazing woman. She’s incredible and has this indomitable human spirit. She was in an arranged marriage at 14, had six kids and a number of children who had died.

“She is so self-possessed, determined and dignified, and she is a really quite strong driver of why we felt we wanted to make the film.

“It seemed that this wasn’t something people were talking about. I’m sure people thought it was probably worse than the UK but I don’t think people thought about it being such a big problem. Also, we felt there was a very powerful women’s movement in Turkey fighting back against these horrible crimes and exhibiting such audacity and bravery and outrage, and that fed our outrage and was a really strong motivation to make the film. Their spirit inspired us.

“In the film, someone says, ‘We’re tired of being sad – now we’re angry’. That’s how a lot of women all over the world are thinking – ‘we’ve been sad, we’ve asked for protection and now we’re just getting really angry’.”

The documentary reports that more than one in three Turkish women have experienced domestic violence, the highest proportion in economically developed nations.

Activists say the problem is being worsened by political rhetoric from the Turkish government, with president Recep Tayyip Erdogan commenting that men and women are not equals, and steps like withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention on combating domestic violence.

Protests and marches have been met with police opposition and tear gas, all set against a volatile political climate which featured an attempted coup followed by mass imprisoning of lawyers, a referendum granting increased presidential powers, and anger that the legal system fails to get justice for victims and survivors.

Kirwan, who is based in Edinburgh, said: “There is a culture that comes from the top that feeds down into the problem of domestic violence. And I think that you can see that in a lot of different countries. The attitudes towards women and who you play to in the crowd are important. I don’t think any world leader would say ‘yeah, we’re in favour of domestic violence’.

“But they are also attacking the people who are trying to fight against it and their rhetoric does have an impact on what people think is acceptable.”

The rate of femicide – defined as the murder of women and girls, mainly motivated by their gender – is rising. The estimated number of deaths in the past year ranges from 300 to 409 but the real figure could be even higher.

Survivors include TV news reporter Kubra Eken, who worked for business network Bloomberg and, at 28, married a fellow journalist. Two days after she gave birth to their daughter, he battered her skull four times, leaving her in a coma for two months, with a haemorrhage and brain damage.

While she was in a coma, her husband took custody of the child. She had to undergo years of intensive therapy to learn to speak or even sit up, but finally was able to testify against him in court and got her daughter back after seven years.

He was convicted of the attack but sentenced to just 15 months, with time off for good behaviour.

Kirwan revealed: “So far he’s not served any time. There’s this idea that you could get a reduction in sentencing because you could say ‘she made me do it’ or there was provocation.

“In the end Kubra’s husband didn’t argue that, but he still got a reduction for good behaviour even though he kidnapped his daughter and she didn’t see her from when she was two days old until she was about three or four.

“Kubra’s family have peace now. They have her daughter back, which is the real victory, and wouldn’t have been able to do that without first proving she had been assaulted.”

Personal victories like Kubra’s custody of her daughter and Arzu’s ability to live and work despite losing both legs and most functionality of her arms, are beacons of hope and feature alongside the tireless work of campaigning lawyer Ipek Bozkurt, who represented them both.

Bozkurt, who will attend special screenings of the film in Scotland over the next two weeks, is a leading figure in the fight against femicide and domestic violence.

In the film, she describes her fight to change Turkey, saying: “This is a country that is protecting murderers who want to punish their wives, their daughters, and their girlfriends for wanting different things than before.”

Kirwan said: “Ipek is such a charismatic person, a really hard-working lawyer and a very relatable character. She’s a feisty, great woman to work with, and she has that anger that we fed into as well.

“She is representative of a lot of women in Turkey. She was able to explain to us on a very nuanced level, rather than just being ‘why did this guy hit this woman?’, why this society is having this problem and she’s incredibly eloquent at explaining that in a way we never could.”

Dying To Divorce has been lauded at festivals and nominated for a British Independent Film Award. And it will fly the flag for the UK in the best international feature film category at the Academy Awards. Of the Oscar entry, Kirwan said: “That was amazing for us considering we’re a team of about five people. It was tough going to get the film made and it’s kind of crazy this is happening.

“I feel like it’s also so good for the women involved. It’s a long haul making this film for them, and we kept going back to them saying ‘Please make time for us’, and we were saying ‘It’s gonna be great and people are inspired.’ But it’s good that it’s all paid off.”

We are not sad any more, we are angry: Producer on why women all around the world have had enough

The turbulent political events and the acute nature of the domestic violence and murder in Turkey are at the centre of Dying To Divorce.

But producer Sinead Kirwan said the UK also had more to do to protect women, following several high-profile murders and major increases in domestic violence figures during lockdown.

She said: “The last few years have seen massive cuts to domestic violence services in the UK and Covid has really highlighted that if you don’t put money and support services in place, more women die.

“You can’t always change individual behaviour but there are concrete things you can do that can dampen the effects of the violence, like funding women’s services and police taking women seriously when they complain about violence.”

She was shocked by the scenes in London earlier this year when protesters at a vigil for murder victim Sarah Everard accused the Metropolitan Police of heavy-handed tactics.

“We did a preview screening for cast and crew in March and in the film you see the women’s day protests being attacked with tear gas and literally a week or two later you had the vigil for Sarah Everard, and the parallels were really chilling.

“That’s what we mean by you have to keep your guard up, because things can slip quite quickly.”

Kirwan added: “In the film that’s where you see the connection between domestic violence and problems with the state, when you literally see the state attacking people who are protesting for women’s rights in Turkey.”

Dying To Divorce is in cinemas now. There are special Q&A screenings in Inverness, Glasgow, Dundee and Edinburgh, from Tuesday. Details at dyingtodivorce.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM