The towering trees swayed slightly in the breeze as they moved slowly up Leith Walk.

In a parade of carts drawn by horses, as residents stood in wonder, the greenery was being moved to a new home as what would become one of Edinburgh’s most popular landmarks took root.

The arresting scene opens Sara Sheridan’s latest novel, The Fair Botanists, set in 1822 when the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh was being painstakingly moved, plant by plant, from Leith to Inverleith.

“The technique of transporting these huge trees by cart was invented by the head gardener, William McNab, who is one of the characters in the book,” said Sheridan, who lives near the famous gardens.

McNab, who was appointed in 1810, was eager to develop the garden and pressed for it to be moved from its cramped five-acre site near Leith Walk with its dilapidated glasshouses to the current 70-acre plot.

He was backed by the new regius keeper Robert Graham, who was appointed in 1820.

Graham, who is also a character in the novel, negotiated for a new site at Rocheid Estate at Inverleith and the massive undertaking began to transplant the entire garden, including trees and shrubs, some of them more than 100 years old.

McNab, formerly of Kew Gardens, was an expert in moving evergreen trees and shrubs, and used what became known as “McNab’s transplanting machine” during the three-year upheaval.

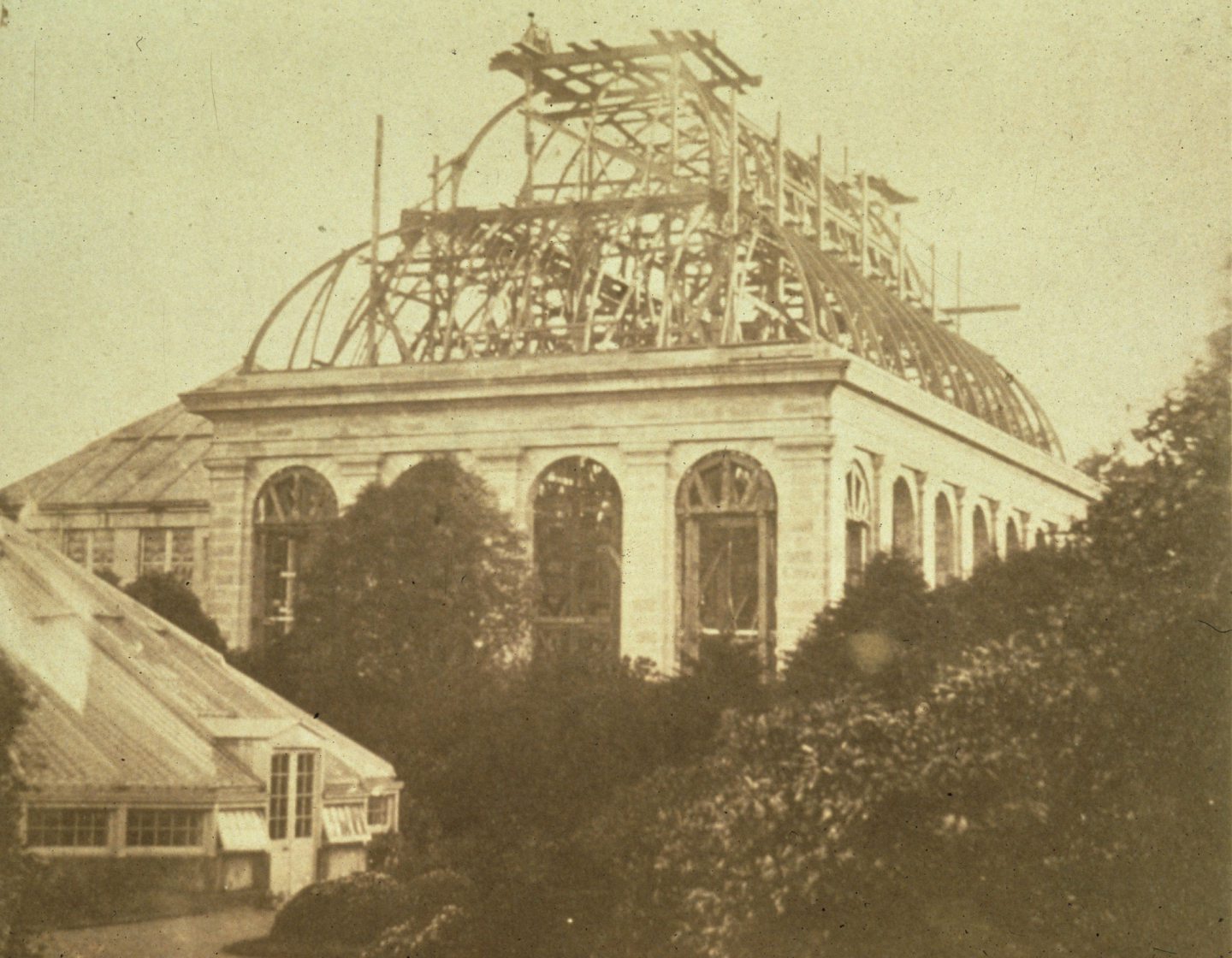

The new garden was a wonder, with glass and palm houses that allowed exotic plants to flourish.

Plants arrived from all over the world and the Edinburgh attraction also supplied other botanic gardens and individuals. In 1826, the tsar of Russia sent McNab a diamond ring to thank him for his help in the acquisition of plants for the imperial botanic garden at St Petersburg.

“Robert McNab’s notebooks are in the archives and make fascinating reading as he details his pioneering method of transplanting 40ft alders and more than 5,000 plants with 10 horses and six men,” said Sheridan.

“The book is like a time machine, taking you back to the Georgian period, when the wealthy moved out of the Old Town and into the New Town, which was quite flash with people dressed in colourful clothes – one of my male characters drives a purple carriage and wears a bright red jacket.

“There were no railways so people arrived by boat at Leith, and tea, coffee and chocolate were expensive and exotic luxuries.”

The Fair Botanists transports readers back to the year when King George IV visited the city, an event that coincided with the botanic garden’s move to the outskirts of the fashionable New Town, which was still being built.

The plot centres on botanical espionage, with various people, including Graham, trying to steal the flowers and seeds of the rare “Century Plant”, Agave Americana, that was rumoured to bloom once every 100 years.

“Industrial espionage was rife in the 19th Century as there was a lot of competition between horticulturalists,” said Simon Milne, the 16th regius keeper in the 351-year history of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

“We still have the same Agave Americana plant and have to remove a pane of glass in the roof when it blooms, which is more like every 30 years in reality,” added Milne.

Another remarkable plant in the garden’s tropical glasshouse is the Corpse Flower, a rare endangered specimen from West Sumatra. Since its arrival in 2003 expert nurturing has enabled it to flower three times since.

“The flower emits a foul stench while in full bloom to attract pollinating insects, and each flowering allows our botanists to further develop their knowledge of this remarkable plant, aiding long-term conservation efforts,” said Milne.

Today, the Royal Edinburgh Botanic Garden welcomes more than a million visitors a year and plays a vital role in the study and conservation of plants – the herbarium collection has more than three million specimens, representing about two-thirds of the world’s flora.

In 2019, work began on the Edinburgh Biomes, which will help secure the future of the garden as a world leader in plant science and horticulture.

The seven-year, £80 million project will protect the garden’s 13,500 plant species, and includes refurbishment of the glasshouses, the construction of a new glasshouse, and new research facilities.

Inverleith House, formerly an art gallery, will become Climate House, which will highlight the global risk to biodiversity through an immersive installation created in collaboration with Australian artist Keg de Souza.

“The garden has never been so relevant as it is today. Life depends on plants, for food, shelter, medicine and to mitigate climate change, but 40% of plant species are threatened with extinction due to changing land use, the impact of climate change and biodiversity loss,” said Milne.

“By studying plants’ DNA sequence, we are building up a better knowledge of plants, which underpins conservation, and are working in partnership with 40 countries around the world. We also propagate and plant vulnerable species back in the wild to save them from extinction.

“Every plant has its role to play in the ecosystem.

“While everyone knows about the conservation and repopulation of charismatic animals such as the beaver and lynx, we are quietly getting on with saving plants that are just as vital to the natural cycle.”

Edinburgh Botanics’ colourful history

Over the last 351 years, the Botanic Garden has moved four times and has grown from a small physic garden, used for growing medicinal plants, to a world-leading conservation, teaching and research centre with rare plants from more than 150 countries – some of them extinct in the wild.

It began in 1670 as the Royal Physic Garden near the Palace of Holyrood. It moved to Trinity Hospital, now the home of Waverley Station, in 1675 and to Leith Walk in 1763 and Inverleith in 1820.

The purpose of the garden was to supply fresh plants for medical prescriptions and to help teach medical botany to students.

The garden was an essential part of any doctor’s training, and one of the more unusual alumni was James Barry, who qualified in 1812.

Born a woman, Barry lived her life as a man, studying medicine at Edinburgh University before a distinguished career as a British Army surgeon. Her true identity was only discovered after her death.

Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, studied medicine in 1877 at Edinburgh University and botany at the botanic garden. Doyle has Dr Watson say of Holmes: “Knowledge of Botany: variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening.”

Women, too, have played their part in the scientific study of rare plants there. In 1916 Lilian Snelling was appointed botanic artist.

Her work captured microscopic differences between species of plants. In acknowledgement of her expertise, Snelling was awarded the Victoria Medal of Honour

in 1955, the highest horticultural award in Britain.

Memorable moments include a Spitfire crash in 1941. Tragically, the pilot died when his parachute failed to open in time.

A recent excavation of the site uncovered parts of the plane.

In 1968 a huge storm caused massive damage to one of the glasshouses and the tropical palm house.

An ancient tree, the Sutherland Yew, which was moved to Leith Walk in 1763 and to Inverleith in 1822, was blown completely to the ground.

Nine years ago, 100mph winds destroyed 500 panes of glass and 40 rare trees were blown over, some of them more than 100 years old.

The Fair Botanists by Sara Sheridan, Hodder & Stoughton, is out now.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Lynsey Wilson

© Lynsey Wilson © Karol Kozlowski/imageBROKER/Shutterstock

© Karol Kozlowski/imageBROKER/Shutterstock © Supplied

© Supplied © Bao/imageBROKER/Shutterstock

© Bao/imageBROKER/Shutterstock