We have all learned to take our joy where we can find it during lockdown but even then, blindfolding your dad and driving him to The Gorbals seems an odd highlight.

For actress and playwright Eilidh Loan, however, it was the last step in a long journey that has forged a stronger relationship with her father Garry.

When his blindfold came off, the big reveal was of a poster on the city streets for his daughter’s play, Moorcroft, based on the stories of his youth.

It explores friendship, pain, love and what it means to be a “real man” in working-class Scotland, centred around a group of young men playing amateur football together.

Translating the stories to the stage saw Eilidh and her father get to know different sides to each other, including their shared experiences of struggles with mental health.

“My dad is my best friend,” she said. “He’s my hero. I grew up inspired by his music taste, our wardrobes are the same, we dance to Northern Soul together and I’ve always been inspired by the stories of him as a young man.

“As I went through my mental health journey, he opened up and shared his experiences and a lot of that filtered into the times he played football. We discussed this and there was a name of a team he played with, Moorcroft, that really stuck in my head.”

The play opens at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow this month, the latest milestone in a flourishing career. The 24-year-old has starred as Mary Shelley in a touring production of Frankenstein, as well as having a role in the most watched film on Netflix over the festive period, A Castle For Christmas.

It was on long drives from the family home in Erskine to drama school in Guildford that she would ask her dad about growing up in the ’80s, an age when men didn’t talk about their feelings. She took notes of the stories, characters and opinions and the play started to come to life.

She explained: “It follows the story of Garry at 50, delving back into his past and wanting to relive his youth in order to change past events or right wrongs, but also just enjoy the times and try to find the sense of purpose again.

“People can’t believe that a woman has written it as the boys can be quite masculine and laddy at times. Having been in the company of some of the boys the characters are inspired by I think they all are like 16-year-olds again when they’re together!”

One of Eilidh’s goals is to bring stories of working-class people to new platforms. “At no point do I want to paint the characters as these heroic figures because at points we don’t like them, we should disagree with them,” she said. “But through that, that’s what makes them so remarkable and that’s what makes them so important.

“My dad and the people the characters are based on, they find it so bizarre. They don’t think they did anything of value with their lives but the opinions that they’ve had in that timescale that have changed, that’s the remarkable thing about them.

“There are some dark moments. That’s something I didn’t want to shy away from. I don’t want to patronise people that come to the play. I want to have the grit and the real life on stage.

“My parents have had messages from friends saying they’d never been to the theatre but they’ve bought a ticket to come and see this.”

Loan is “unbelievably proud” of the man her father is today and will never take the relationship she has with him for granted.

“When I was a teenager, talking about mental health was still such a taboo,” she said. “If that’s how I felt, how did my dad feel back when he was a boy?

“What we’ve learned is that I can have an anxiety attack and be able to phone my dad and we can talk each other through that. It’s pretty remarkable the two of us speak openly about what we have experienced.”

Loan will be eternally grateful for the support her family have given her to help her in the pursuit of her dreams. They’re the first people she shares the news with when landing a role, or even just getting an audition.

“Anything I can do to make my mum and dad proud is amazing,” she said. “When you get a phone call to say you’ve got an acting job or your show’s been picked up and you get to share that with your parents who have sacrificed a lot, it’s the best feeling in the world. That beats doing the job.”

The whole family sat down in their pyjamas on the sofa to watch A Castle For Christmas, in which Loan played knitter Rhona alongside Cary Elwes and Brooke Shields.

“It’s quite a surreal experience, taking the bins out and then sitting down and watching yourself,” she said.

Living in lockdown and having lost family members, Loan said the opportunity to star in the rom-com came along at the perfect moment.

“It was the most rewarding and amazing experience to jump on to a set and make something really fun,” she said. “It would’ve been difficult to have done something a bit gritty or sad at a time where the world is sad and we as a family were grieving.

“We sat for a week learning to knit, and Brooke was like my fairy godmother. She was the most amazing woman to work with and such a huge inspiration. I learned so much from her.

“It was the best experience I’ve had on set. It was magical. Christmas for three or four months!”

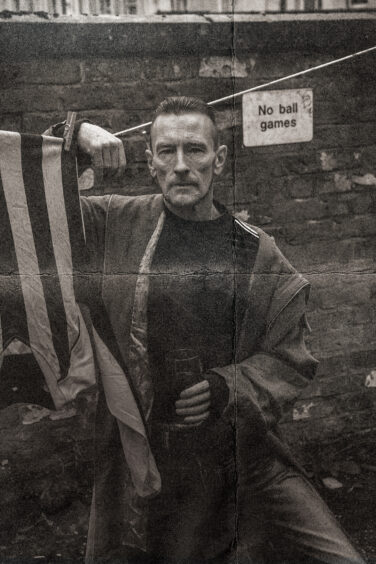

A father’s pride in a daughter whose writing cuts through to the other side of men’s lives

Watching Moorcroft come to life, Garry Loan couldn’t be prouder of his daughter’s work.

Alongside wife Karen and Eilidh’s younger sister, Erin, the 54-year-old is her biggest fan.

“Even when she phones us up to tell us that she’s got a self-tape audition to do, that still gets to me,” he said.

“It’s that proud moment that folk are interested in her. If she gets the part, even better. I always think she deserved it for the work she’s put in. I think it makes it better that it’s not just been handed to her.”

Loan, who works as a tiler, has been pivotal to his daughter’s play Moorcroft, which draws heavily from his own experiences growing up in Renfrew in ’80s.

He admits it’s a strange feeling for him and some of his football-playing friends to essentially be recreated and recast on stage with their vulnerable sides shining through via his daughter’s writing.

“She’s seen through to the other side of them,” he said. “They’re like this on the front but what are they like when they’re not in a group of people, in their own homes sitting on their own, having their own thoughts, not having to show off or to be the big man?

“You’ll know a character in that play that’s your uncle, your grandad, your brother, your best mate.

“The way these guys tell stories, it’s not like modern days where everything is on computers or all these devices, we’re in a circle telling stories when we get together and talk.

“There are these great storytellers. The stories sometimes aren’t that good, it’s just the way they tell them. This is what’s gone into Eilidh’s play – the way she tells the stories.”

Through the play, father and daughter have learned a lot about each other, particularly about their shared struggles with mental health.

Talking about it, Loan says, is the most important thing.

“When I was young you could never say anything like that,” he said. “You’d be laughed out the dressing room. It was a no-no, you’d be treated differently and you’d be out the team. So you bottled it all up.

“I learned from Eilidh that you can’t go through life like that. It wasn’t until probably my late 30s, early 40s, that I started telling anybody the way my mental health was.

“Even my close pals, some of the guys that are in the play, said they’d never have thought about it because back then you had to hide it that well.

“I’d go to the pub after a game, have three or four pints and be laughing and joking, but then go up the road and that would be me, couldn’t get out of bed for two days. But they didn’t know that.

“The play touches on that, being scared to say anything. Eventually I had a bit of a dark time in my life, and I had to say something to my friends. I think it was more of a relief for them than myself to know there was something wrong with me but it could be fixed, I’d get back to an even keel.

“We’d lost quite a few guys to cancer, drugs and drink already. They couldn’t be any more supportive.

“I don’t think I could have done it 20 years before that.

“I’ve learned from my kids and my wife that talking is the bit you need, it gets you through it.

“We’ve learned to keep talking. Most of it’s a load of rubbish but as long as you keep talking you’ll get through it.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM