The new Conservative Prime Minister claims the country is paralysed by a controversial Eurosceptic trade deal.

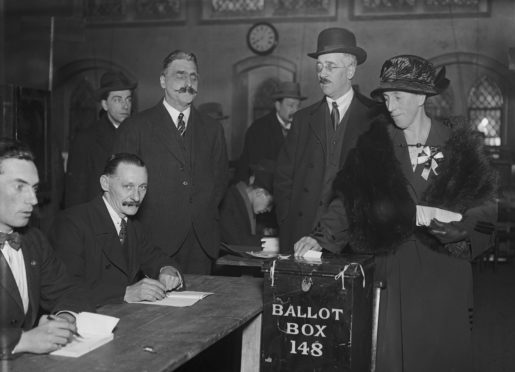

To solve the deadlock, he calls a rare winter General Election to fend off challenges from Labour and the Liberals.

The subsequent, bad-tempered campaign is marred by bitter threats of violence against candidates, and claims of Russian influence.

Welcome to the General Election of 1923.

The similarities between the political landscapes then and now has not escaped political historians.

Professor Martin Pugh, author of State and Society, A Social and Political History of Britain since 1870, believes both elections could have been avoided.

“There are parallels of various sorts. To start with the politics, 1923 was clearly an unnecessary General Election that the Prime Minister of the day called because he was trying to manage a very divided party.

“There was no reason to have it, as the Conservatives had won an election in 1922. The difference was they had a big majority – but the party was split about foreign tariffs. It was all about managing the party.

“The other similarity was that something occurred that might occur after this campaign. The Conservatives didn’t gain a majority but they were the largest party.

“Labour and the Liberals had to unite to throw Baldwin out – which they did. It is not too unlikely that something similar might also happen this time.”

The Conservatives’ decision to go to the polls in December almost a century ago was down to concerns about foreign countries and the effect on the British economy.

Dr Timothy Peacock, a lecturer in Modern History at Glasgow University, and author of The British Tradition of Minority Government, which examined the 1923 General Election, said: “Post-war unemployment and industrial action led to Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin wanting to introduce tariffs on imported goods to stimulate the economy.

“There were also fears of increased economic competition from other countries.

“Labour had also recently changed leader in 1922, and the Liberals continued to suffer from the splits within the Party.

“This suggested the political climate was favourable to the Conservatives – which echoes some of the comments on modern opinion polling.”

Although the election might not have been necessary, it proved similarly contentious – especially when it came to foreign trade.

“The 1923 campaign was divisive,” added Dr Peacock. “There was not that much time to prepare the political ground, causing splits between pro-free trade and pro-protectionist wings of his party.

“Even among newspapers supporting protectionism, there were differences of opinion over the form of tariffs, which only served to harm Conservative electoral support.”

The current campaign has seen Labour’s spending plans dismissed as extreme – a tactic deployed in the 1920s, too. “The Labour Party was steadily rising but large parts of the press painted them as having connections with the Communists,” added Professor Pugh.

“The ironic thing of course was that Ramsay MacDonald was doing his best to come across as moderate, they didn’t even have any socialist policies at that stage. So a lot of the propaganda then was a lot of hot air.

“Like Jeremy Corbyn, Ramsay MacDonald was often painted as a dangerous extremist. His role as an opponent of Britain entering the First World War was often raised against him but I’m not sure if that was damaging.

In fact, by 1923 his past record was almost an asset because by then the reaction against the war was really quite strong.

“And this gave MacDonald a lot of credibility. In many ways, it’s similar to Corbyn’s opposition to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which we now widely recognise as total blunders.

“Although it’s interesting that Corbyn perhaps doesn’t get similar credit as MacDonald did.”

Candidate safety has been an issue in the current election two years on from the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox and The Sunday Post reported on threats of violence from so-called “smasher gangs” who were disrupting hustings. They were, according to The Post, steered by “foreigners”, an apparent reference to Russian revolutionary influence on Red Clydeside.

Violence and threats towards politicians were relatively common, according to professor Pugh.

“In the Victorian period especially, they could be riotous, drunken affairs,” he added.

“Back then, No 10 Downing Street wasn’t fenced off so would occasionally be beset by crowds who would force their way in and give dignitaries and cabinet ministers a very rough time – verbally as well as physically.”

The outcome of the 1923 election saw the Conservatives emerge as the largest party, but Labour, with support of the Liberals, was able to form a government.

With the growth of smaller parties in modern times – such as the SNP in Scotland – a parliamentary majority is even more unlikely.

“When considering parallels with 2019, it is important to bear in mind the changed electoral arithmetic,” said Dr Peacock.

“After the 1923 election, all but eight of the seats were held by the Conservatives, Labour, or the Liberals.

“At the end of the recent parliament, more than 100 seats were held by seven parties and Independent MPs with different objectives. Gaining a parliamentary majority in modern times is even more challenging.”

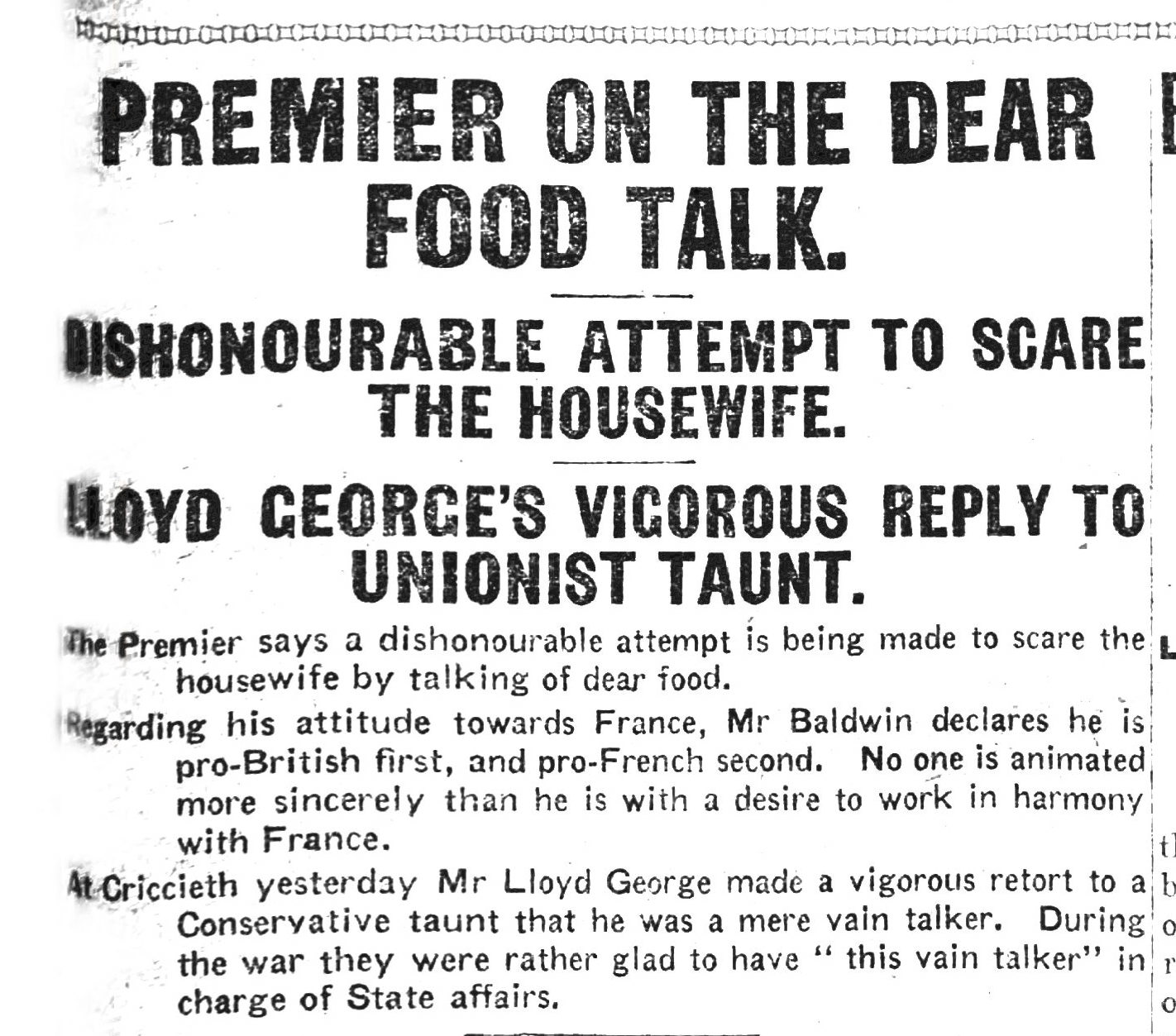

“The Premier says a dishonourable attempt is being to scare the housewife by talking of dear food,” it starts.

The report reveals Stanley Baldwin saying that the main breadwinner in a million homes is out of work, but when jobs are found, food will get cheaper not more expensive as opponents claim.

Meanwhile, Lloyd George hit back after a Conservative poster had called him a “vain talker.”

He concluded: “There is no party in the State which has less right to issue that poster than the Tory Party.”

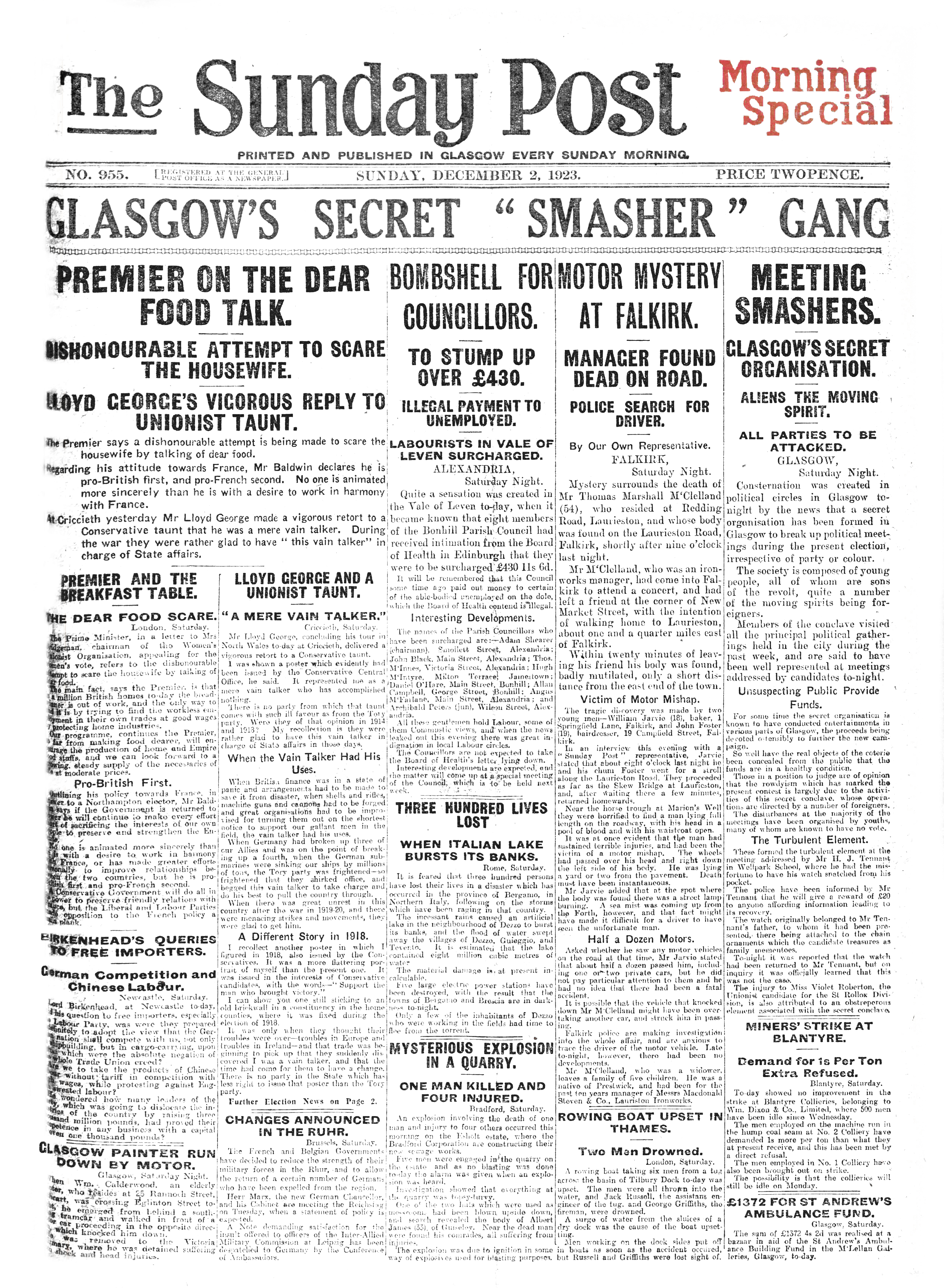

“Consternation was created in political circles in Glasgow tonight by the news that a secret organisation has been formed to break up political meetings during the present election, irrespective of party or colour.”

The story’s intro was to the point but the report goes on to suggest many of the “moving spirits” of these “sons of revolt” were foreigners, in an apparent reference to the Russian Revolution in 1917.

The youths being blamed for the trouble at hustings are accused of stealing a watch from one candidate and a Unionist candidate in St Rollox, Miss Violet Roberton, was injured by an “obstreperous element associated with the secret conclave.”

Bad blood on the hustings

“The Premier says a dishonourable attempt is being to scare the housewife by talking of dear food,” it starts.

The report reveals Stanley Baldwin saying that the main breadwinner in a million homes is out of work, but when jobs are found, food will get cheaper not more expensive as opponents claim.

Meanwhile, Lloyd George hit back after a Conservative poster had called him a “vain talker.”

He concluded: “There is no party in the State which has less right to issue that poster than the Tory Party.”

Smasher gangs’ Red links

“Consternation was created in political circles in Glasgow tonight by the news that a secret organisation has been formed to break up political meetings during the present election, irrespective of party or colour.”

The story’s intro was to the point but the report goes on to suggest many of the “moving spirits” of these “sons of revolt” were foreigners, in an apparent reference to the Russian Revolution in 1917.

The youths being blamed for the trouble at hustings are accused of stealing a watch from one candidate and a Unionist candidate in St Rollox, Miss Violet Roberton, was injured by an “obstreperous element associated with the secret conclave.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

© Topical Press Agency/Getty Images © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images