To Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny they are a “modern-day Sherlock Holmes” for exposing how the Kremlin allegedly poisoned him.

To despots and dictators, they are a thorn in the flesh as their sleuthing reveals evidence of terrible crimes.

To supporters, however, the Bellingcat website investigators, led by founder Eliot Higgins, are shining a light on the world’s darkest corners.

Bellingcat, dubbed “an intelligence agency for the people,” have deployed open-source intelligence (OSI), information freely available on social media, smartphones and the web to expose everything from locating terrorist training camps to revealing state-sponsored crime and human rights atrocities. They even found a lost dog.

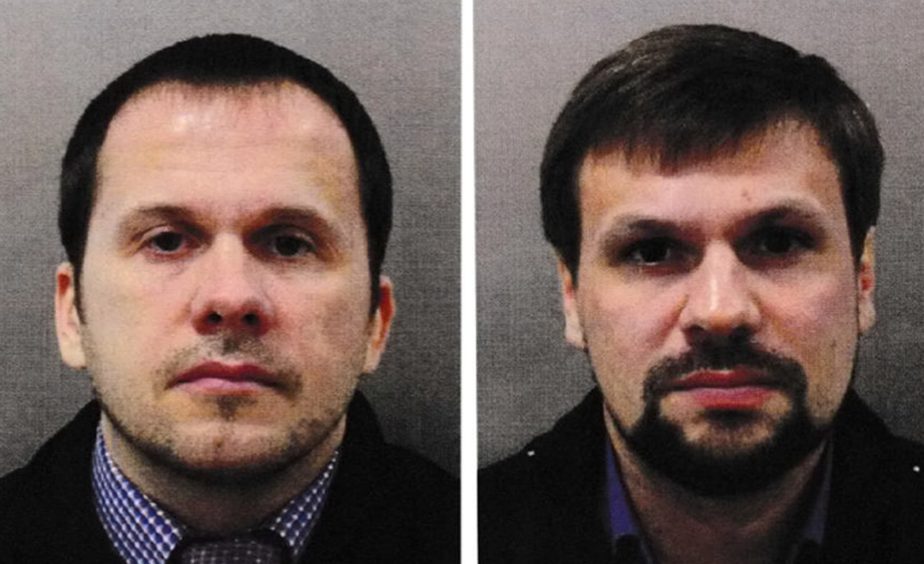

The site’s most spectacular successes include identifying the two Russian agents behind the Salisbury poisonings, detailing what happened to Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 and proving Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons on his own people.

Higgins has detailed the organisation’s work in a book, We Are Bellingcat. It charts the journey from his blog to an acclaimed investigative force, making enemies at the highest level of governments around the world.

“It’s about producing information that is based purely on evidence that can inform people about what’s happening in different parts of the world,” Higgins explains.

“We involve the people in the process itself and produce a product they can see and understand, not just a bunch of information being leaked out randomly or us saying we have a source and you can trust us.”

From a blog to a worldwide force

Bellingcat grew from Higgins’ obsession with current affairs, particularly during the Arab Spring in 2011. While working in admin, he was a regular blogger under the name Brown Moses, sharing information he’d found online.

“I was just a bit frustrated about how the conflict in Libya had been reported on when there was such a vast amount of OSI. I could see there was a use for it,” he said.

“I was always writing for myself, never for an audience, and was frustrated that the bloggers that were using this material were often using it for conspiracy theories, making huge leaps of logic.

“I accidentally stumbled into quite big stories. It grew, and I gained a fairly decent reputation among journalists and other people in the community and just wanted a site where I could have people host articles and also learn how to do investigations.

“It was always really about building a community of people who could research and investigate, rather than keeping it as my sort of special thing.”

That sense of collaboration has become core to Bellingcat, as well as their founding idea of “identify, verify and amplify.”

Higgins added: “It’s quite unusual to show exactly how you’re doing stuff and where all the information is. People like to have their secrets and their special sources, but we’re like: ‘Here’s everything.’”

Bellingcat’s work came to international attention following the downing of MH17 in 2014, in which 298 people died. They figured out that it had been hit by a Russian Buk missile by looking through images posted online and mapping. They also found its deployment involved senior Russian officials.

Higgins said: “It was a proud moment for us in 2016 when the team investigating MH17 gave a press conference.

“It was a scary moment as we were a bit worried they might disagree with us, but they agreed with everything we were saying. That was big for Bellingcat and OSI as a whole as it then led a lot more people to take it more seriously.

“They saw that our work had been validated by an official investigation, and that OSI was a real thing that worked and not just kind of a magic trick.”

Using similar methods, they unveiled the identity of one of the two suspects in the poisoning of the Skripals.

They also uncovered evidence showing Moscow’s FSB security service targeting Navalny, an anti-corruption activist and opponent of Vladimir Putin, who survived a Novichok poisoning.

All of these discoveries came from hours of pouring through information online. This could be finding connections between people on social media, sketching out a map of military movements seen on a YouTube clip, or matching satellite imagery to pictures posted to Twitter to determine an exact location and times.

Often, the material can be traumatic. The Bellingcat team were exposed to countless images and videos of chemical attacks in Syria, and Higgins recalled his distress at finding a toy his daughter has a version of in the wreckage of MH17.

“We’re always very aware of issues like vicarious trauma,” he said of looking out for his fellow investigators. “Syria has produced a lot of horrific material, we’re very careful that they’re not overexposed.

“It can sometimes be easy to see a link and click on it without really thinking about the impact it’s going to have on you.

“One of the worst cases I’ve had of that recently was of the Christchurch shooting where the guy livestreamed it. It was like a first person shooter video game but with real people. This guy was so callous about murdering all these people.

“You don’t need that in your brain. Once it’s in there, that’s the kind of stuff you don’t forget after you see.”

A positive difference

For Bellingcat, fighting falsehoods has become as vital as showing the facts.

A striking example of the power of misinformation manifested on January 6, as supporters of Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol.

“The events in Washington showed how dangerous it can be,” Higgins said. “It could be a fundamental threat to society if we don’t take it seriously. In the US, people got really into an 8chan forum post, built an entire alternative universe around it, and managed to convince thousands of people it was real.

“The Republican party started leaning into it and that’s the danger, where mainstream discourse starts using paranoid conspiracy theories looking for that extra bit of power, that extra vote. Once you abandon the truth in the pursuit of power, then we’re completely screwed as a society.”

Many buy into cyber-miserabilism, the theory that the internet has taken a sledgehammer to politics, debate, civility and created an unfixable mess.

But Higgins and Bellingcat hope that the “immense powers” given to us by technology can be marshalled and continue to make a positive difference.

“Sometimes when you live in a Western democracy it’s very easy just to lean back and think everything’s going to be fine and you don’t really have to play a proactive role in protecting democracy,” he explains.

“It’s too easy to think someone else will sort that out. And whilst you’re doing that, you’ve got a bunch of people on the internet convincing each other that the earth is flat, coronavirus is fake and Bill Gates is putting microchips in vaccines.

“The people who believe in the truth, democracy and evidence just kind of assume that that’s the natural state of things, but the internet is a place where what’s natural is social media platforms recommending you whatever they think you want to look at through an algorithm.

“If you click on a flat earth video and get recommended another one and another one, you end up getting drawn into alternative media ecosystems where you’re completely detached from reality.

“We need to be proactive about that, and that’s why at Bellingcat we try to build a community around our work and OSI because it’s one way to have a healthy community online.”

Part of Bellingcat’s work now is about archiving raw footage, social media posts and images from conflicts in Yemen and Syria in the hope that one day there will be a full set of data to draw from to bring those responsible for human rights breaches to justice.

Video clips from Syria, Higgins said, are of equal value to World War Two diaries in that regard.

“We’ve been working to develop a process around archiving and investigation so we can put together case files that are effectively things we can just hand over to any kind of court or judicial process which needs information on the incident we’re investigating, so they know it’s been done in a systematic fashion.

“We’re doing mock trials to see how this stuff can be challenged in court so we can at least develop a minimum standard for a way of working that allows this material from conflict zones to be preserved and used in a useful way.

“It makes that information a lot more useable and accessible to all the kinds of bodies who might want to use it, not just legal proceedings but policy makers, researchers and other people.”

Personal safety

With all that Bellingcat has uncovered and the powerful forces involved, Higgins has received countless anonymous threats online, and the group have experienced a number of cyberattacks.

But, at home in Leicester, he remains unfazed, more worried about the potential actions of an individual rather than a state, and taking Russian interference in their work as a compliment.

“It shows it does matter to them that we’re doing this stuff. They might say we’re working for the CIA or MI5 but ultimately, they’re worried about what we’re doing. It’s the best advertising when Russia Today, Sputnik or some official has a go at us. It shows we’re doing something right in most people’s eyes.

“The police talk to us about our own safety. I know that’s the risk of our work. I know the positive impact our work is having and that there are some things that are bigger than your own personal fears and safety.

“It’s not great, but there are more important things in the world and you do sometimes have to make a choice to stand up to things. If you can’t stand up you’re sitting doing nothing.”

And the work is not always about big conspiracies and Russian hit squads. “You can have influence big and small,” Higgins said. “Last year I helped find a dog that was stolen, using a number plate analysis technique we’d previously used in murders. It was a few hours work, a nice thing to do.

“On the other side of the scale we’ve got a huge amount of work on Russian assassinations. We were told by journalists on the ground in Russia that protestors were on the streets as a direct consequence of our investigation into the poisoning of Navalny.

“It’s nice to help people who have had their dogs stolen, it’s a positive impact.

“This is why when I talk about building communities, it’s not just about hunting Russian spies, it’s about having a positive impact on a more personal level sometimes. That counts for something.”

We Are Bellingcat by Eliot Higgins, is published by Bloomsbury

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock

© Shutterstock © Supplied by Bloomsbury

© Supplied by Bloomsbury

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock © Lev Radin/Pacific Press/Shutterstock

© Lev Radin/Pacific Press/Shutterstock © ANDY RAIN/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

© ANDY RAIN/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock © Babuskinsky District Court Press Service via AP

© Babuskinsky District Court Press Service via AP