Elizabeth David did more than anyone else to change the way we eat, cook, and think about food.

In a 2012 poll for the Diamond Jubilee, Radio 4 listeners voted her one of the top 60 Britons to have lived in the current reign. A year later, the Royal Mail exalted her with a first-class stamp.

Since 2016, her Chelsea home has boasted an English Heritage Blue Plaque while the likes of Julia Child, Prue Leith, Simon Hopkinson, Nigella Lawson, Nigel Slater and the late Jane Grigson have called her their biggest influence.

Yet, of all David’s prizes – a 1976 OBE, the CBE a decade later, two honorary doctorates, and French anointing as a Chevalier du Mérite Agricole – she most cherished the 1982 day when she became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

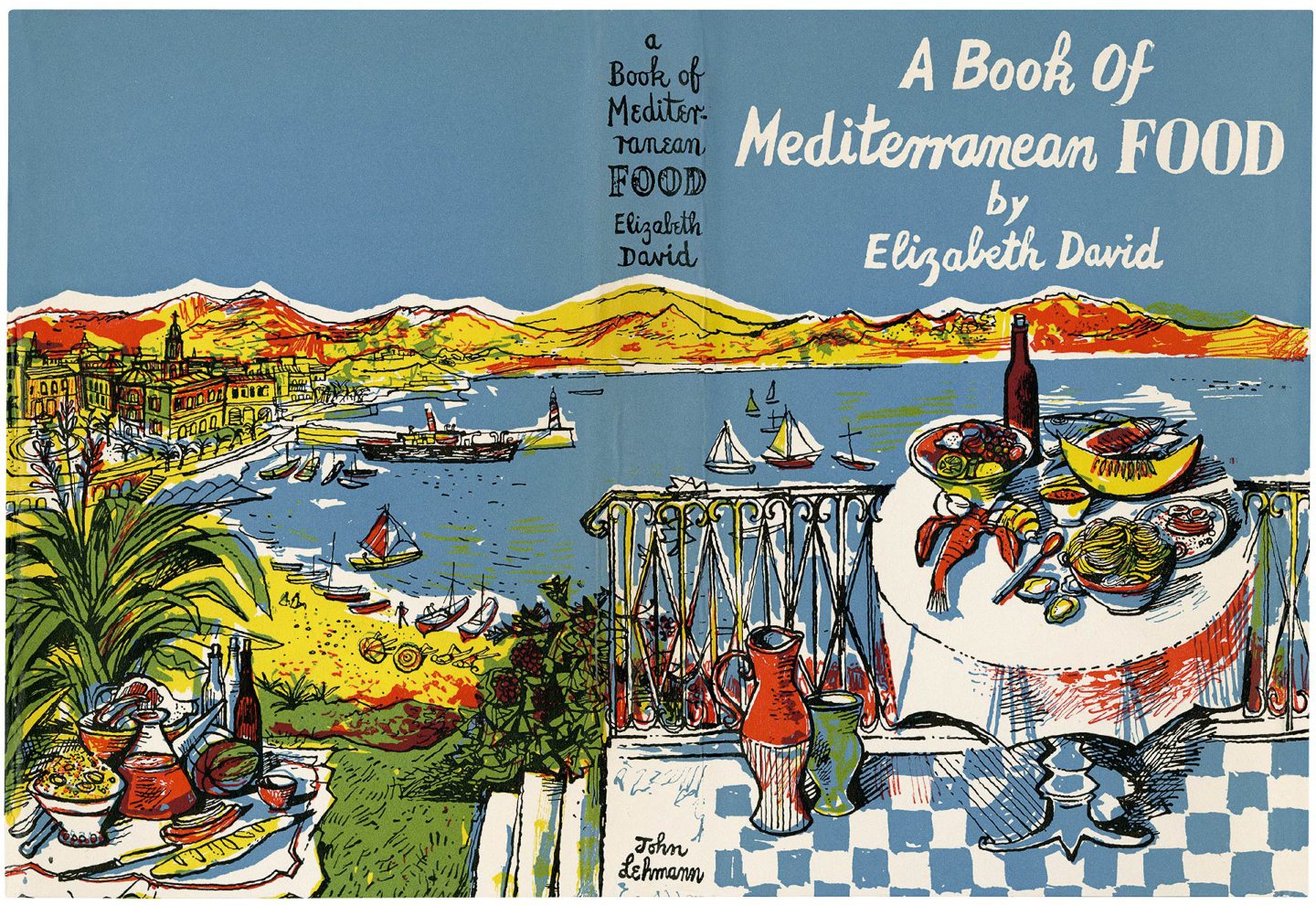

Justly, for from the first page of her first book – Mediterranean Food, which burst upon drab, drear Britain like a thunderbolt – she simply painted with words.

“The ever-recurring elements in the food throughout these countries are the oil, the saffron, the garlic, the pungent local wines; the aromatic perfume of rosemary, wild marjoram and basil drying in the kitchens; the brilliance of the market stalls piled high with pimentos, aubergines, tomatoes, olives, melons, figs and limes; the great heaps of shiny fish, silver, vermilion or tiger-striped, and those long needle fish whose bones so mysteriously turn out to be green…”

Looking back, 30 years after her death, her career seems even more unlikely. She only once ever appeared on television, in 1989 (it was a disaster). Her only radio interview, with Derek Cooper in 1982, was…fraught. Jealous of her privacy, she simply refused to play the “celeb”, or pose for the Sunday supplements with a large, dripping spoon.

And her books are books – plain prose that sparkles and fizzes, with minimal line-drawings; not the lavishly photographed gastroporn de rigeur today.

And, while they sold most respectably, and sell still, Jamie’s 30-Minute Meals – published in 2006, and the fastest-selling non-fiction book in history – has alone shifted far more copies than Elizabeth David’s entire prose.

David was, from the start and to this day, a food writer for the educated and thoughtful. Sir Terence Conran, founder of the celebrated Habitat chain, was an early fan – and yet even those who knew her well admit she was a very difficult woman.

Well into middle-age she was noted for intrigues and affairs. She drank more than was wise. Mocked close friends behind their backs. She had uneasy relations with her publishers and detested editors.

Anyone who crossed her was cut. She particularly loathed Robert Carrier, arguably Britain’s first celebrity chef – for he had once passed off a David recipe as his own. But behind all this lay much that was sad.

All who knew David attest to her elegance. The slightly severe suits, the perfectly tilted hat, the way she glided into a room or took her seat, taking in the scene with vast, cat-like eyes.

Elizabeth Gwynne was born on Boxing Day 1913 in Wootton Manor, East Sussex – daughter of Rupert Gwynne, Tory MP for Eastbourne, and his wife Stella, daughter of the 1st Viscount Ridley. Into a world of flowered hats, domestic servants and gentle suppers with Nanny. And there were Scots antecedents too – doughty iron-foundry types in Lanarkshire.

For many summers, she would enjoy a little holiday north of the border, with a particular fondness for a borrowed bungalow in Gairloch. “Rain drumming on the corrugated iron roof makes a stimulating background rhythm for my work on the index of a book about Italian cooking,” she reflected in 1962. “In what other climate could one do three months’ work during a fortnight’s holiday?”

The sudden death of her father, in 1924, was a dreadful blow for her and her three sisters. She was of a class that expected but a basic education for young women, finishing-school, time abroad to polish at least one modern language, and then the securing of a respectable husband.

At 16, she was duly sent to Paris; and, after 18 months of France and the French, went on similar ends to Munich. But she already dreamed of being an artist and, still worse, upon her 1932 return to Britain now determined to become an actress.

She joined various companies, had the odd small part, meanwhile tried to teach herself to cook – and began untold entanglements with mostly unsuitable men.

The most significant was one Charles Gibson Cowan, who bought them a boat, dumped his wife, and sailed off with David on a voyage to the isle of Aegean by way of the canals of France – optimistic, in July 1939. They had reached Marseilles when Hitler invaded Poland, and so wintered at Antibes, where she struck up an unlikely friendship with the crusty Norman Douglas – writer, scholar, of Deeside gentry.

And a predator, unable from 1917 to return to Britain after abusing young boys. She probably never knew that but was hugely influenced by him in other respects. Douglas was immune to any sense of sin: “Always do what you damn well like, and let everyone else go to hell.”

He cherished privacy, that of others as much as his own – “I like to taste my friends, not eat them.” And he had fierce views on food – that basil should be torn, not chopped; that a man “who is stingy with the saffron is capable of seducing his own grandmother”.

As David’s authorised biographer, Artemis Cooper, pointed out in 2007: “He taught her a kind of authenticity – know when something is second-rate, and don’t accept it.”

To make a long story boring, Elizabeth and Charles’s passion did not long survive internment in Italy, confiscation of their boat, near-penniless exile on a Greek island and final flight as the Germans advanced – first to Crete (it was promptly bombed) and then to Cairo.

She got rid of him, spent the rest of the war in Egypt – working for our Ministry of Information – and married, in August 1944, Lt Col Anthony David. Within two years she could no longer stand yet another afternoon watching her husband play polo.

She returned to England, on her own, in August 1946 and, though there were spasmodic attempts to try again – they would not formally divorce till 1960 – their marriage was now effectively over.

Yet, like Muriel Spark – with whom she had much in common – David discarded an ill-judged husband while astutely keeping his surname. Through that dreadful winter – Britain’s hardest last century – she took a room in a Ross-on-Wye hotel. It boasted roaring fires and hot-water bottles. But its appalling food made her a writer.

“It was worse than unpardonable,” she recalled in 1963, “even for those days of desperation; and, oddly, considering the kindly efforts made in other respects, produced with a kind of bleak triumph which amounted almost to a hatred of humanity and humanity’s needs.

“There was flour and water soup seasoned solely with pepper; bread and gristle rissoles; dehydrated onions and carrots; corned beef toad-in-the-hole. I need not go on. We all know that kind of cooking. It still exists.”

So, one day, she lifted her pen: “Even to write words like apricot, olives and butter, rice and lemons, oil and almonds, produced assuagement. Later I came to realise that in the England of 1947, those were dirty words.”

Harper’s Bazaar gladly published her wistful articles: by 1950, she had enough material for a book. By the time it reached John Lehman, who loved it, A Book Of Mediterranean Food had been spurned by every publishing-house in London. She began each chapter with a literary anecdote or allusion.

Lehman added evocative illustrations by John Minton. Mediterranean Food sold well, and won warm reviews. After all, it was not so much about cooking as longing. This was a Britain where meat, butter, eggs and fats would be rationed till 1954.

Throughout the war, the production of cream had been forbidden. Lemons, tomatoes and even onions were still hard to obtain, and olive oil was something available only in very small bottles, usually from the chemist and for relieving earache.

David never looked back. French Country Cooking followed in 1951. An extensive tour of Italy begot Italian Food, in 1954: Evelyn Waugh pronounced it one of his two favourite books that year. Summer Cooking came out in 1955 – the first to display her impressive grasp of the best British dishes – and, in 1960, French Provincial Cooking, widely thought her greatest work.

But the ’60s were unkind. Elizabeth’s heart was broken in 1963 when her last great love, Peter Higgins, finished with her. After an ill-judged Moroccan holiday – and she was still not 50 – she had a stroke, and her sense of taste was never the same again.

She launched a cookware shop in Pimlico, bankrolled by some friends. But they wanted profits – she refused, for instance, to sell garlic presses, convinced they were utterly useless objects – and she was soon ousted from the enterprise.

It yet traded under her name, and there was nothing she could do about it. She resumed writing – Spices, Salts And Aromatics In The English Kitchen (1970) and English Bread And Yeast Cookery (1977).

That same year she survived a car crash but never fully recovered. Many cherish her collected journalism, An Omelette And A Glass Of Wine (1984); Harvest Of The Cold Months: The Social History Of Ice And Ices was published posthumously.

Her last meal was some caviar and Chablis. She died that night – May 22, 1992 – and was buried at St Peter’s, Folkington, where she had been christened. She had her foibles. To the amusement of her friends, she loved Roka cheese biscuits, and never met coffee she thought as good as Nescafé.

But she insisted on utter kitchen integrity. Foods eaten in season. Fresh herbs. Freshly ground pepper. Authentic regional recipes. Taste, taste, and taste again. She had an entire horror of fussy garnishes, cutlet frills and so on, and her favourite repast was simple: that omelette and a glass of wine. Perhaps some home-made pâté to begin; afterwards, some fresh salad, and a few figs or strawberries.

Her legacy is enduring. Once, mused Jane Grigson, “Basil was no more than the name of bachelor uncles, courgette was printed in italics as an alien word, and few of us knew how to eat spaghetti or pick a globe artichoke to pieces…

Then came Elizabeth David like sunshine, writing with brief elegance about good food, that is, about food well contrived, well cooked. She made us understand that we could do better with what we had.”

Like his father, Auberon Waugh had no doubts. Elizabeth David, he said, was “the single person most responsible for most improving British life in the 20th Century.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock / Olga Popova

© Shutterstock / Olga Popova © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM