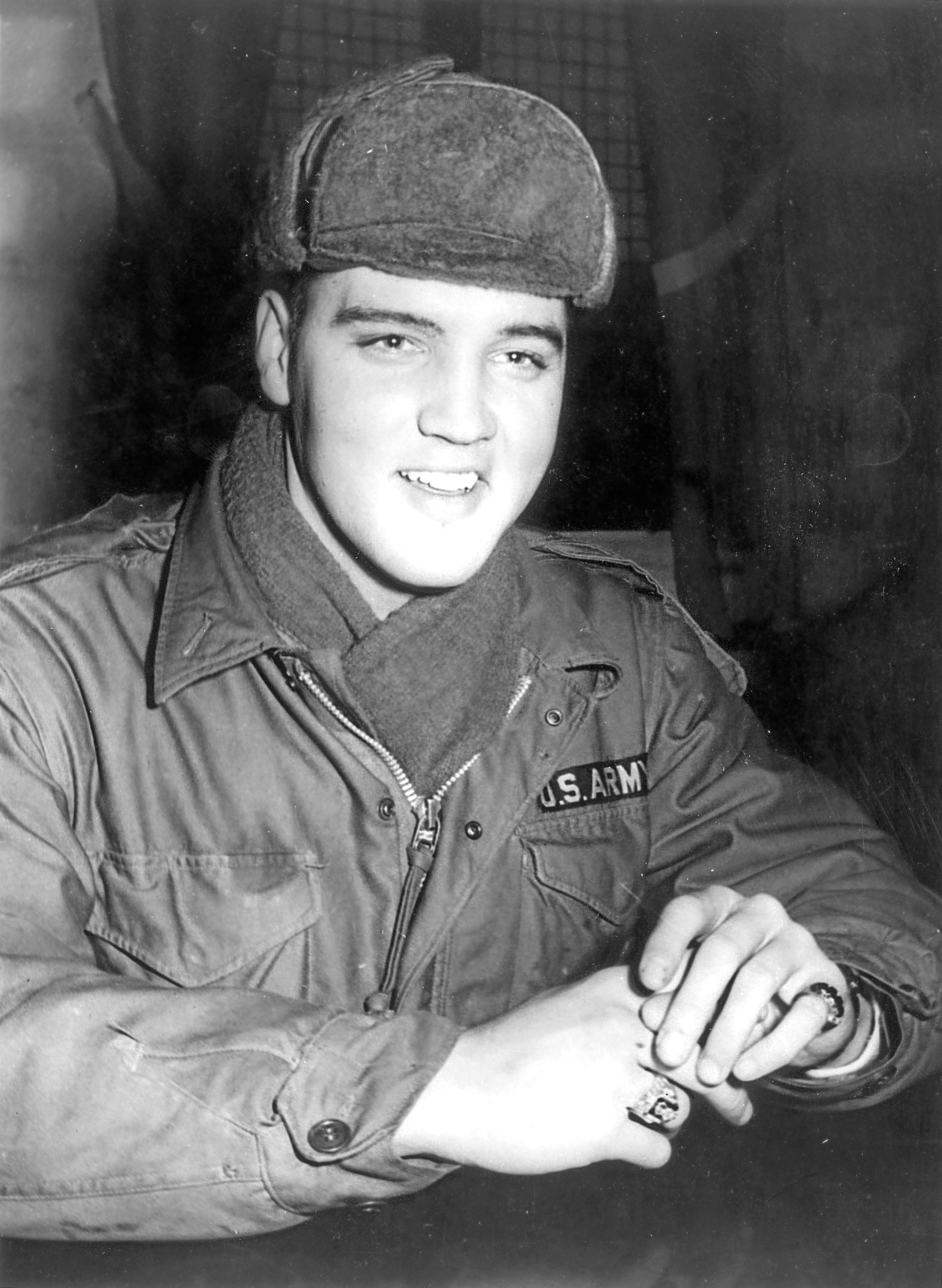

TO the US Army, he was service number 53310761. To his fans, he was simply “The King”.

It’s incredible that, at the height of his fame and the biggest name in the world of entertainment, Elvis Presley could be drafted and spend two years in uniform.

But that’s what happened 60 years ago, in March, 1958.

Elvis’s time in the Army turned out to be two of the most pivotal years in his life.

Parents played huge role in shaping Army Private Elvis Presley

His beloved mother, Gladys, died before he was sent to Germany, and while he was there, he met future wife Priscilla, and developed a dependence on stimulants and barbiturates that would lead to divorce and untimely death aged just 42.

That said, on his release from serving Uncle Sam, he found new older fans thanks in part to his Army career.

It all started on January 8, 1956, when Elvis turned 21 and became eligible to be drafted.

His manager, Colonel Tom Parker, knew two years out of the public eye could end his client’s career. He wrote to the Pentagon requesting Elvis be considered for Special Services, which would allow him to do just six weeks basic training, then get back to showbiz — albeit with the expectation he did several shows a year for the armed forces.

These would be unpaid performances, which the Army would film and record for sale to TV stations around the world.

And that was a problem.

There was no way Parker, an inveterate con man and shyster, would let anyone profit from his golden goose apart from himself.

So Parker led Elvis to believe he’d avoid the draft, while himself believing that, after 12 months marred by negative publicity — with parents branding Presley a “menace to society” because of his hip-swinging brand of the Devil’s music — a spell in the military would change public perceptions of his star.

Elvis was livid, but a medical on January 4, 1957, passed him 1-A and he was told he’d receive his draft notice on December 16.

Even then, he had escape routes. The Navy said they’d create a special “Elvis Presley Company” made up of his pals from Memphis, and offered him the chance to perform in Vegas and have private quarters.

The Army said he could visit bases to improve morale and encourage young men to enlist, while the Pentagon indeed offered a chance to join Special Services, known to enlisted men as “the celebrity wimp-out”.

Elvis discussed it with Parker, but was persuaded that “taking any of these deals will make millions of Americans angry”.

What the Colonel didn’t say was that he thought a stint in the service would lengthen his career by showing him to be a normal young man, and would cure Elvis of rebelling against his guidance.

Parker also didn’t want the authorities to take a closer look at his own service record.

He wasn’t a Colonel. He was an illegal Dutch immigrant whose time in uniform had ended with being charged with desertion and discharged due to a psychosis developed while in solitary.

Presley was due to be inducted on January 20, 1958, but got a deferment to complete King Creole. Worried rock and roll was a passing fad, he wanted to make this his best picture so that, after two years out of the limelight, he could return as a dramatic actor.

Parker made sure he had enough material and merchandise stockpiled to keep Presley’s name in the public arena. He’d have 10 Top 40 hits during his two-year hitch, including One Night.

On March 24, Elvis was sworn in, made leader of his group and, in front of news crews from around the world — thanks to the Colonel — said his goodbyes and set off by bus to Fort Chaffee, Arkansas.

Four days later, he was transferred to Fort Hood in Texas and assigned to Company A of the Third Armored Division’s 1st Medium Tank Regiment.

He became a pistol sharpshooter and said he enjoyed the “rough and tumble” of the tank obstacle course.

But to those who knew him best, he confided he was homesick and would often break down in tears during calls home.

Elvis’s mum died shortly before he was assigned to the Third Armored Division in Friedberg, West Germany. His leave after basic training was extended on compassionate grounds.

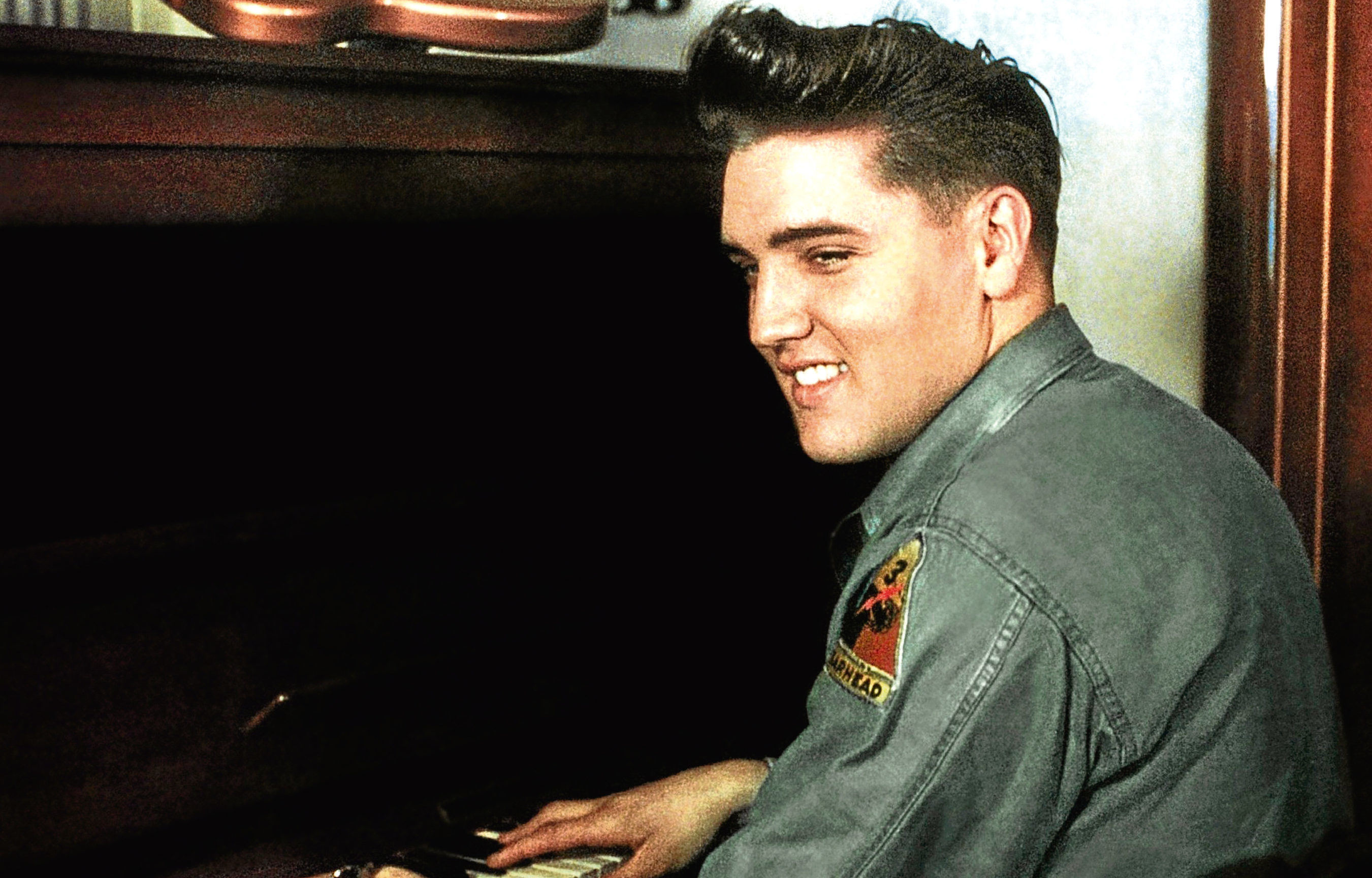

In Europe, he again refused to join Special Services, so was assigned duties driving for a reconnaissance platoon sergeant.

Elvis was keen to be seen as an ordinary soldier, and was very generous to his fellows, donating his pay to charity, buying TV sets for the base and an extra set of fatigues for each man in his outfit.

But he was allowed to live off the base and moved his family into the elegant Hotel Grunewald, with Parker having to dispel rumours of wild parties.

Parker wrote to Elvis every day as he was very busy, making deals for records and movies, with Paramount agreeing to pay $175,000 to make what would become G.I. Blues after his return.

The Army introduced their new recruit to karate, which became a lifelong obsession, but they also introduced him to amphetamines which Presley praised for energy, strength and weight loss.

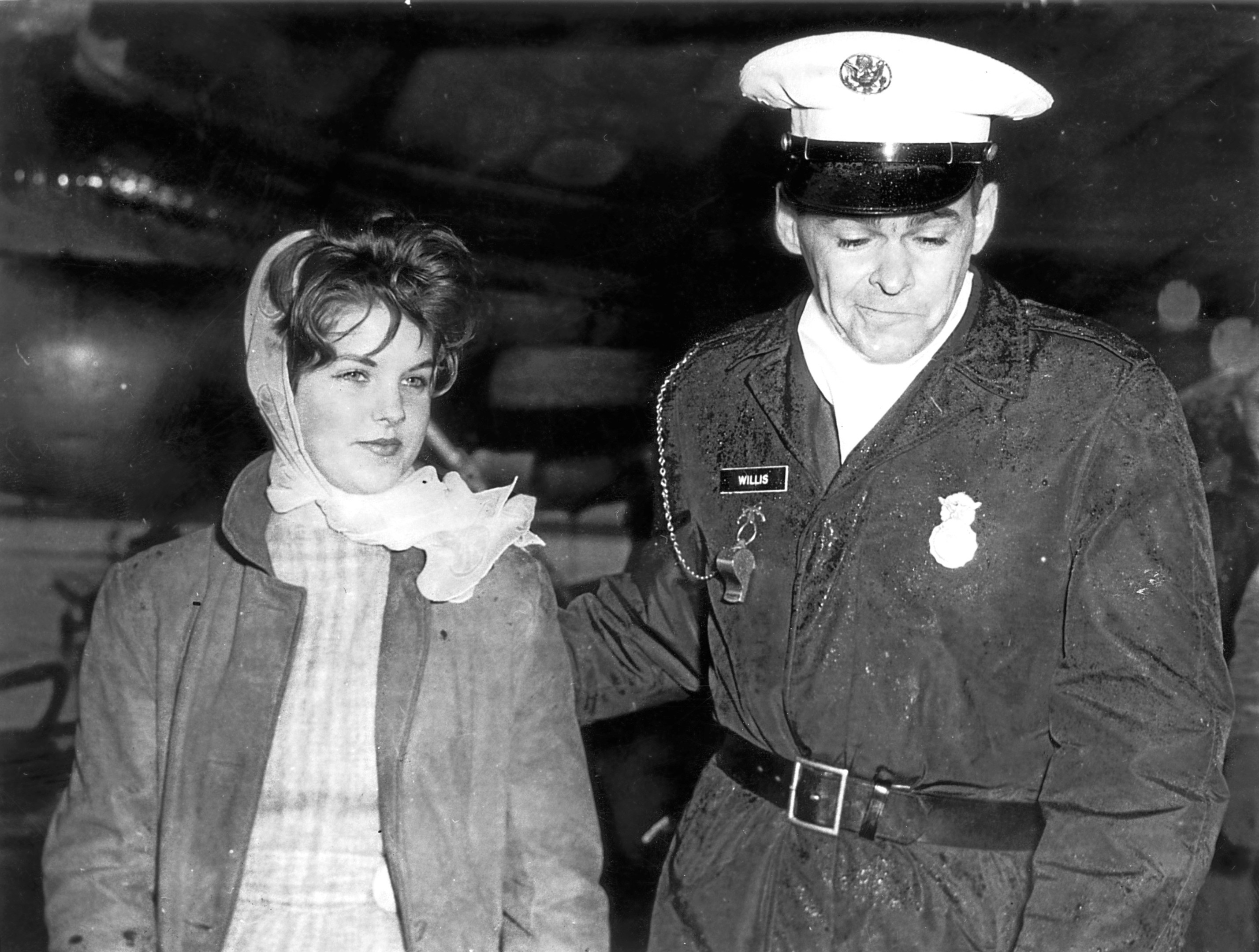

Speaking of introductions, on September 13, 1959, he was introduced to Priscilla Beaulieu, then 14, at a party. They became inseparable and would marry seven and a half years later.

On March 1 the following year, the Army held a press conference as the newly-promoted Sergeant Presley prepared to return home.

He said: “People were expecting me to mess up, they thought I couldn’t take it. But I was determined to go to my limits to prove otherwise.”

And so Elvis flew home, setting foot in the UK for the only time when his transport refuelled at Prestwick in Scotland, and on March 5 he was officially discharged from active duty.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe