“I think a lot of actors become actors because they want to hide,” admits Emily Watson, star of Gosford Park and Chernobyl. “I don’t know if I’m necessarily that, but I’m not comfortable with the spotlight on me, Emily”

“That’s not why I do it,” she continues. “I love the sense of creating and inhabiting something; that feeling of making it feel magically real. That’s the addiction.”

In her case it’s a good addiction to have. The twice Oscar-nominated, five-time Bafta-nominated, one-time Bafta-winning actor (in 2011 for her role in the TV series Appropriate Adult) has been a regular presence on our film and TV screens since she made her remarkable debut in the controversial director Lars von Trier’s 1996 film Breaking The Waves.

Her name on a cast list is itself a marker of quality. She is, if you like, the Faberge of contemporary actors, turning out glittering performances time after time.

Soon we will get to see her in the fantasy adventure The Legend Of Ochi and she is involved in the TV spin-off of Dune, The Sisterhood.

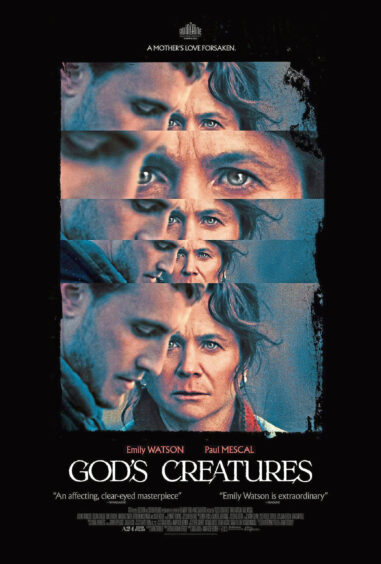

“I’m on the Dune train,” she says. “I’m in the Dune universe which is pretty thrilling, a bit of a departure for me. There is the possibility that it goes beyond a series, so that’s not anything I’ve ever done before.” But before any of that there is the new Irish film God’s Creatures, where Watson gets to play Paul Mescal’s mum.

The movie is the reason that Watson is edging reluctantly into the spotlight today. She is in Scotland for its UK premiere at Glasgow Film Festival. It is a couple of hours before her red-carpet moment and she is in a city hotel talking to broadcasters and journalists doing her bit to promote a film she is clearly very proud of.

And no wonder. She is, as ever, remarkable in it. Played out against brooding skies and huge seas, God’s Creatures is set in a remote Irish fishing village. Normal People actor Mescal plays the prodigal son returning home, much to the joy of his mother. But when he is accused of sexual assault she has to weigh up how far a mother’s love can go.

Set in a pre-mobile phone Ireland, it’s an elemental story about smalltown conservatism. If you took out the cars you could imagine it taking place in the 19th Century. Watson would go back further.

“It read to me like a Greek tragedy,” she suggests. “There’s an impending doom in it. It’s like a series of bombs going off.”

The film was shot in Donegal at the height of Covid. “We were on the coast in total lockdown,” Watson recalls.

“Because I was British I’d had one jab but none of the Irish cast or crew had any. And so there was a sense of threat, definitely. But the producer was incredibly scrupulous. There were testing circles around us which meant it never came anywhere near us. We were very protected. It was amazing, actually.

“We were all staying in our little cottages in isolation. I was on the coast of Donegal on my own for a week which was a very intense experience, rehearsing on Zoom. And then, when we were finally sprung and all got together as a company, just the energy, the physical kinetic sense of ‘let’s do this,’ was really great.”

It’s a film that is told through Watson’s eyes; from the light in them when her character first sees her son return to the very different look in the final scene itself.

It’s a film about maternal love and the danger inherent in that. She has two teenage children herself. Did being a mum help her play the part?

“Obviously there are aspects of my experience,” she says. “That sense you could lift up a car, feeling that you are an animal and you will defend your young…That sense of your range as a person just being expanded by having children.

“But it’s an actor’s job that for those things that are not in your lived experience you go off and imagine them. Otherwise, I’d only be playing nice middle-class English girls.”

She could never be accused of that. To play the cellist Jacqueline du Pre in the film Hilary And Jackie, Watson spent three months learning to play the cello, practising so much that her fingers bled.

And she made her name at 29 in Breaking The Waves as a naive young woman in a repressive Scottish community who marries a Danish oil rig worker, played by Stellan Skarsgard. When he breaks his neck in an accident at work he asks her to take other lovers, much to the horror of her friends and the disapproval of the community.

It is a remarkable film but also a very difficult, painful one. I’ve never been able to watch it a second time, I say.

“That’s a good plan,” she says smiling. Watson’s performance is raw and powerful but it’s worth remembering it’s exactly that. A performance.

“You’re very lucky if you have the knack of just landing in something in a way that doesn’t feel effortful,” she suggests.“It’s all about your collaborators really.

“As an actor you’re nothing without all the other people in the room. And if you get the right combination of all of that then you can rock up in a way that it feels like, ‘Oh, you are that person,’ rather than trying to force it in any way.”

It was a Lars von Trier film but she didn’t know what that meant at the time. She says: “A lot of people didn’t know what that meant. It was a very fresh experience for an audience as well.”

There is an intensity to Watson on screen so it’s maybe not a surprise to know that she once said: “Acting, if you’re doing it right, you’re traumatising yourself.”

Does she really think that? She insists: “In a sense, yes, because you’re treading the neural pathways that your character is going through. Obviously it’s not real and you’re not having that actual experience but your body doesn’t know the difference, necessarily. So, you have to be quite careful about making sure it’s very clear this isn’t real and let it go.”

Watson was brought up as a nice middle-class girl in north London. Her mum was a teacher and her dad an architect. But she attended the School of Economic Science which she has described in the past as a “kind of religious set-up” and admitted she saw incidents of cruelty there.

“I was raised as a guilty soul,” she once said of the experience.

There was no TV in the family home, but there were books. Stories were a way to escape. She says: “Oh, massively, escaping out of the proscribed ‘this is how things are’ sense of what my childhood was like and riding on other people’s magic carpets off God knows where. Yeah, huge.”

Is the woman she has become shaped by that childhood? She says: “Oh yeah, very definitely. It was quite strong and quite intense but I survived it…I’m probably the stronger for it.”

These days Watson is 56, married to Jack Waters after they met while both acting at the Royal Shakespeare Company.

In her 40s she told a newspaper she wasn’t happy about getting older. I wonder how she feels now? She says: “Oh, I’ve totally given up on that one. But actually I’ve been very fortunate to be on just the right side of the curve. When you hit your 50s roles start being really interesting and actually when you stop bothering about all that stuff it’s very liberating.”

In the wake of arguments over the gender pay gap and the #MeToo movement, the position of female actors has been part of the cultural conversation in recent years. Does she get a sense things are finally beginning to change?

She says: “Very much so. When I did a job a few years ago my lawyer went back to the company and asked, ‘Is she getting paid the same as the men?’ And they came back and my salary increased by a third, which was a really shocking moment because I realised I had always assumed I would never get paid the same. It was just how it worked. It was just baked in. And that’s really a wonderful sense of feeling valued.

“People have worked furiously to change the culture around potential abuses within the way a film set works, the way a company is put together. They’ve worked hard to make that no longer a thing and you can really sense that on sets. It feels safer.”

Not that things are perfect. “There’s still a long way to go in terms of behind-the-camera equality and diversity and all those things,” she points out before returning to the reason we’re here, God’s Creatures, a film that takes in toxic masculinity and the lack of female agency.

Both, she points out, are still very evident in the wider world. She says: “You look at the Metropolitan Police, you look at the online influencers that young people are following.”

But not everything is a council for despair. The other way her industry is changing is in the growing demand for women’s stories to be told on our screens. Female experience is finally being valued.

The Angela’s Ashes and Punch-Drunk Love actress says: “It has been for the last five six seven years and I’ve really felt the benefit of that. With the change in the way that media is consumed – there are all these different platforms and masses and masses of choice and 50% of the audience are women.

“And a lot of them are probably in charge of the buttons.”

God’s Creatures is in cinemas from March 31.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM