FOR four long years British Tommies had been telling each other: “Don’t worry, it’ll all be over by Christmas.”

However, as the war ground on that started to sound like a bad joke in the mud and trenches of the Western Front.

But 100 years ago, in 1918, it really was over by Christmas.

The Hundred Days Campaign had reversed the German gains of their Spring Offensive and that plus the arrival of the USA into the war and the naval blockade strangling Germany meant an armistice was declared and the guns fell silent.

But the end of the war didn’t mean Christmas at home, far from it.

The vast majority of the conscripted British forces had yet to be demobbed by the time December 25 1918 rolled around.

Rapidly realising that a one-way ticket back to Blighty wasn’t on the cards for a while yet, hundreds of thousands of soldiers, sailors and airmen went about trying to replicate the experience and the spirit they’d longed for but to a greater degree than had been possible for the previous four years.

A Christmas menu issued by the American Expeditionary Force’s Base Hospital 202 near Orleans promised hot cakes, fried bacon and apple sauce for breakfast, roast turkey, mashed potatoes and creamed carrots for dinner and, if the “Doughboys” could manage it, a light supper of “pickles, fried beef steak, hashed brown potatoes and corn fritters”.

Canadian John Law had spent five years overseas, first in the Army and then the Royal Flying Corps, and he wrote home to Canada: “In three days it will be Christmas. This is my fourth away from home and I am longing to be with you all again.

“It is such a relief to have come through these past years and be finished with it now. To look forward to the homecoming, the pleasure and real happiness of which, it is difficult to imagine.

“Although it will be past Christmas when this reaches you, my thoughts will be with you on that day.”

Another Canadian, Harold Simpson, found himself on garrison duty in Germany and wrote to his mother: “Thank you for your splendid Christmas parcels, four of which arrived during the week preceding Christmas, the first a splendid fruit cake, the next two chickens, butter etc. and the last that big iced cake on Christmas Day.

“I of course shared them with the boys and the people with whom we are staying. Our Christmas was filled with but one regret and that was in the knowledge that you would miss our presence at the Christmas table.”

Another member of the Allied occupation of Germany, Sergeant Charles Stevenson, was one of the American troops who raised a Christmas tree in Coblenz. He wrote back to Kansas: “Just a few feet from me are members of a typical German family, throwing up a tiny Christmas tree, decorating it thoroughly in accordance with all respect due to the famed Christmas tree.”

Others, having been the focus of their families’ concerns for so long, found themselves worried about those they’d left at home.

Robert Shortreed of the Canadian Field Artillery wrote: “We all expect that fighting has ceased for this war. It has all come very sudden and is hard to realise as I was expecting it would last most of next year.

“Have been watching reports on the Spanish Influenza with concern and sincerely trust you all escape it or at least with no ill effects. It spreads very quickly and Paris, London have just passed the worst of it although after thousands of deaths.”

Some soldiers who had been captured earlier in the conflict were still to be repatriated from their prison camps while others had already been deployed to other war zones such as northern Russia or to garrison far-flung outposts of the empire.

Indeed, British soldiers would fight and die trying to prop up the White Russians after the revolution until October 1919.

Back on what had been the Home Front, people were doing their damnedest to make it a Christmas to remember.

Rationing of sugar, butter, margarine and meat had been introduced in 1917 because of the U-Boat crisis when the Imperial German Navy had sunk fully a quarter of all merchantmen heading to the UK carrying food. So people might have dined on freshly-shot game such as rabbit or pheasant, while shops made a special effort to have favourite festive foods in stock for Christmas.

Obviously, with refrigeration rare, people had to pick up their turkey on December 23 or 24 to ensure freshness.

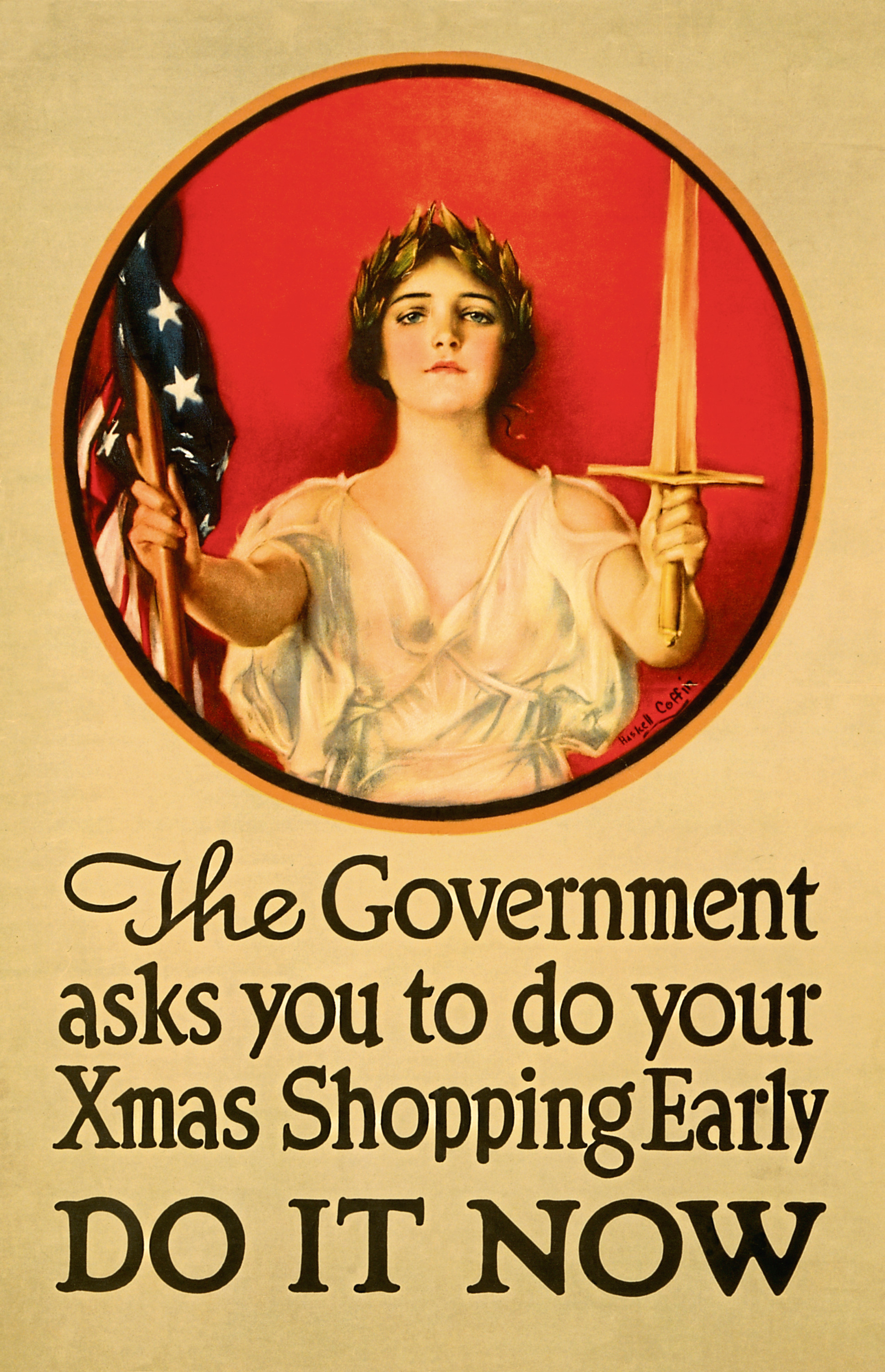

While those on civvy street didn’t have the nonsense of Black Friday, the recently-ended war effort had meant an early start to Christmas shopping.

In America, newspapers had run adverts as far back as October urging people to get their gifts and suchlike early because of the rules issued to retailers by the Council of National Defence.

These were designed to save on coal and petrol and also recognised the fact shops wouldn’t be able to hire as many seasonal employees to deal with demand, as the manpower and delivery vehicles had been deployed elsewhere.

Shops were urged not to increase their sales staff, nor extend opening hours, while the public was asked to buy only useful gifts – except for young children – and carry their packages wherever possible to reduce the need for deliveries.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe