It was only four words. One sentence, in tiny, painstaking handwriting, in one diary entry.

But it was March 24, 1944, and when Alex Lees wrote “Eighty officers escaped tonight,” he was describing what was to become one of the most famous episodes of the Second World War.

The daring exit of 76 Allied officers from a German prisoner of war camp via a tunnel called Harry was to be celebrated for decades to come, inspiring the classic movie The Great Escape.

The film will return to cinemas next Sunday, the 75th anniversary of the escape, for a special screening hosted by historian Dan Snow.

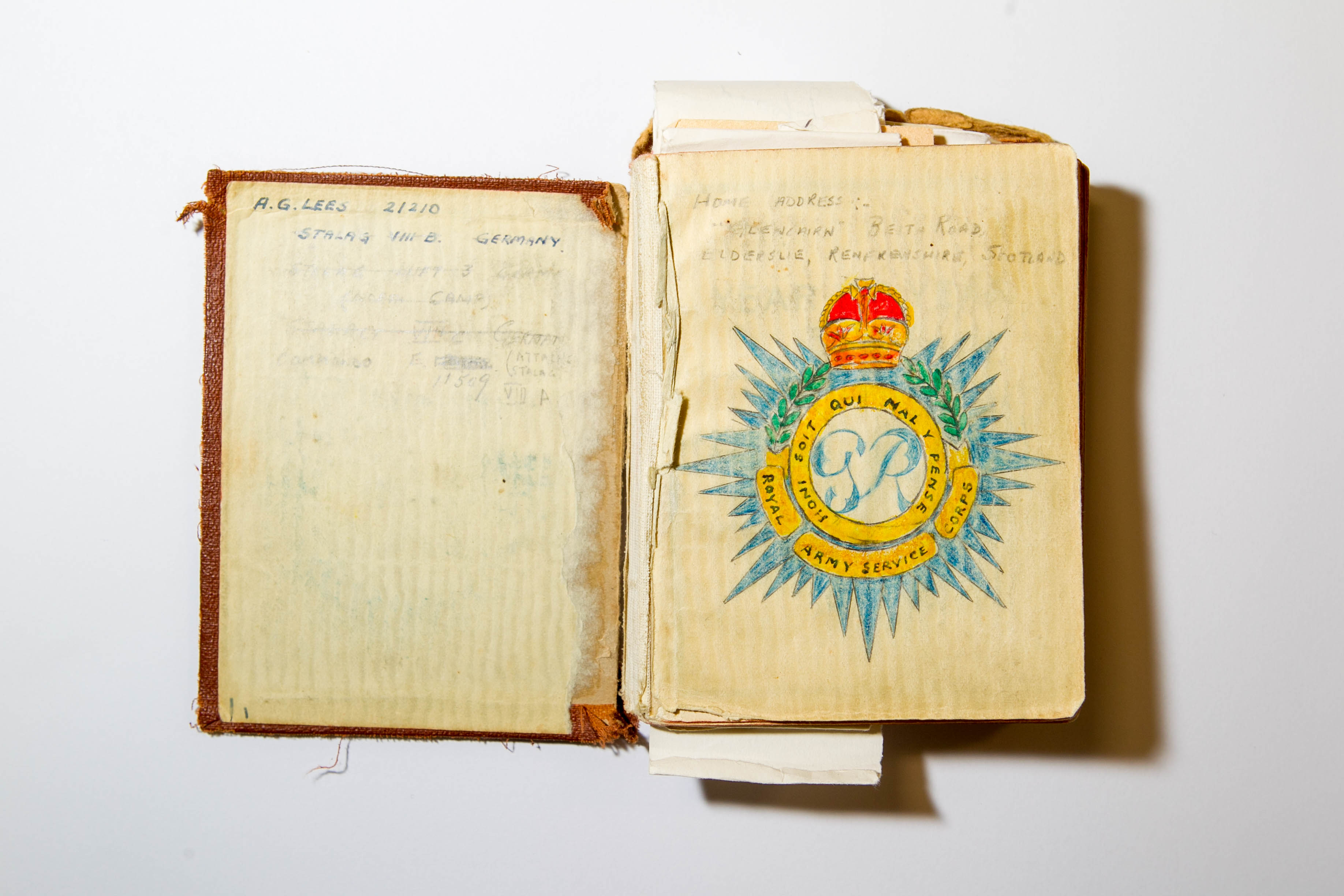

But the previously unseen war diary of soldier Alex Lees, who helped to dispose of the soil from the tunnel while imprisoned at Stalag Luft III, gives a first-person account of the escape.

The tattered notebook, which Alex used from 1942-45, is a fascinating insight into life in a war camp. The diary entry of March 24, 1944, gives scant information of the drama that was unfolding that evening nor of the months of planning that had preceded it.

“Eighty officers escaped tonight. Cloudy and rain. Air raid warning midnight,” was all Alex, from Paisley, wrote.

His daughter, Patricia, describes him as “canny, cautious and clever”…too smart to write anything in the diary that would give the game away.

The reality was that Alex was a “penguin”, prisoners so-called due to their gait as they used sacks hidden inside their trousers to dispose of soil from the tunnels into a vegetable patch he cultivated.

Alex, who died 10 years ago aged 97, was proud of his role in The Great Escape and commended the film for its realism.

“When the film came out he started to think about it more, as it was in the public eye,” said Patricia.

“He thought maybe his story could complement what had already been said.

“My brother, Colin, and I used to love a bedtime story about the war when we were young.

“He always made them adventurous, never scary.

“Into his 90s, he would go around schools to talk to pupils about the war.

“It gave him a purpose towards the end, passing it on to the next generation.”

Patricia visited Stalag Luft III, which is now a museum, in Zagan, Poland, several years ago and donated a copy of the book her dad wrote about his war days.

“It was fascinating and we were made to feel very welcome when we told them about my dad,” added Patricia.

Stalag Luft III was one of many prisoner of war camps Alex spent time in after he was captured in Crete in June 1941 when the island surrendered.

He had only been in the Army for 10 months.

“I just couldn’t believe I was to become a POW and I felt a sense of foreboding,” he said later.

He fought dysentery – his 6ft 2in frame fell to eight stone – and later influenza, and was part of a chain gang, worked down a coal mine and fought frostbite over the next four years. He moved to the newly-opened Stalag Luft III on April 20, 1943, having responded to a notice in his previous camp requiring 100 men to work in an officers’ camp.

This camp for officers was in the hands of the Luftwaffe and was far removed from the previous conditions Alex had been part of, when he had to rake through bins for food.

“It turned out to be a wonderful camp for privileges, accommodation and comfort and there was absolutely no comparison to previous camps we’d been in,” he said.

“We slept between sheets, had pillows and blankets.

“Each hut had a large washroom, cold showers, washbasins and overnight dry toilets.

“It was nicknamed Heaven In The Pines.”

He was moved on from Stalag Luft III in July 1944, which he suspected was due in part to him pretending to be an escaped officer, Flight Lt Thompson, on the night of The Great Escape.

After being liberated on April 11, 1945, Alex returned to Britain a few days later and went back to his job in insurance after demobilisation.

He spent his final years at Erskine veterans’ home, where he was reunited with two men who were also Second World War prisoners at Stalag Luft III.

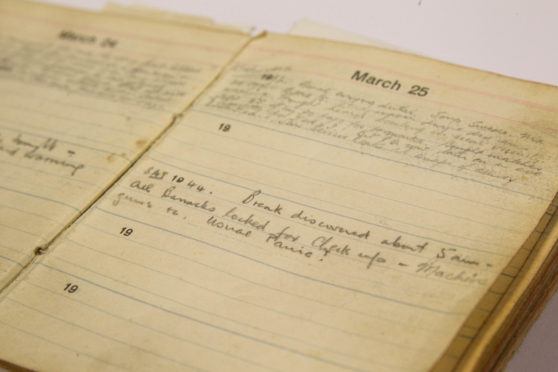

Entries from Alex Lees’ diary chronicle the hours before and after the daring escape from the POW camp in March, 1944

April 23, 1943

Two days at Stalag Luft III, what a change for the better, pretty scraggy after 48-hour train journey from Lansdorf in a cattle truck.

As well as orderly duties at Hut 122, Alex was offered the job of cultivating a plot of ground outside the rooms, using seeds from the Red Cross to grow tomatoes, lettuce, radish and cress.

The garden became the perfect place to dispose of the soil being dug from the tunnels.

Alex later wrote: “The tunnel sand was a different colour than the surface sand and those with garden plots used to assist by dropping the sand either in the bottom of a trench and covering it with the surface soil or raking it in well to disguise it.

“Quite often the security guards would admire the tomatoes, not realising that sand from the tunnel had been in the soil.

“I spent most of my time in Hut 122, but I moved to Hut 104 to be with my friend, Willie Macdonald, who had been a mate of mine at VIIIB.

“The entrance to the tunnel Harry from which the officers made the mass escape was below a heating stove in Hut 104, just a few feet from our room.

“One time, I went to take a shower and was amazed to see a figure emerging through the sump opening in the washhouse floor.”

March 25, 1944

Break discovered about 5am – all barracks locked for check info – machine guns out. Usual panic!

“Escape Committee decided on the morning of the 24th that it would happen that night.

“Moves took place after dark and I remember seeing in the darkness a figure approaching in civilian-like clothes wearing a dark overcoat, dark soft hat and carrying a small case making his way towards the doorway I was leaving. All movements were timed to avoid detection by the vigilant guards and sentries – cloak and dagger stuff alright!

“At 10pm, the first of the escapees went out of the tunnel. A little before midnight, all the lights in the camp went out and also in the tunnel, which was lit by electricity.

“Being plunged into darkness caused a lot of panic until candles on standby gave some light and let the escape continue.

“The all-clear sounded about 2am but the air raid had badly slowed down escape operations, although the darkness outside the tunnel mouth enabled escapers to dash for cover unnoticed.

“The two of us relaxed a bit, until 5am, when we heard a rifle shot. Oh God, the break had been discovered.

“You could hear pandemonium breaking out everywhere.

“We were herded to the main gate, passing Hut 104, where the officers waiting to escape were rounded up, stripped to their underwear and searched.

“Machine guns set up, guards waving revolvers, I thought, ‘Oh help, something is going to happen here.’

“After a big wait, we were told we could go back to our huts. Seventy six escaped, 50 shot, three got home, remainder back to camp.

“While the camp was delighted three got home safely, it was stunned by news of the shootings.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe