The scientist leading the world’s largest plankton monitoring programme fears climate change is already impacting on the microscopic marine life essential to the planet’s future.

The tiny sea creatures vital for life on Earth are moving north in search of colder conditions as the oceans are starting to heat up, according to David Johns, head of the Plymouth-based Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey (CPR). He fears the consequences if climate change continues to warm oceans and plankton cannot reach colder water in years to come.

Last week, we reported fears of Scots researchers after their sampling suggested plankton levels may have fallen by 90% in parts of the Atlantic and their warning that the decline may be seen more generally within 25 years.

Dr Howard Dryden’s team at the Global Oceanic Environmental Survey (Goes) near Edinburgh sounded the alarm after spending two years gathering water samples in the equatorial Atlantic. If replicated, the results would suggest the first link of the ocean’s food chain is in peril, with subsequent impact on other marine life including fish, dolphins and whales.

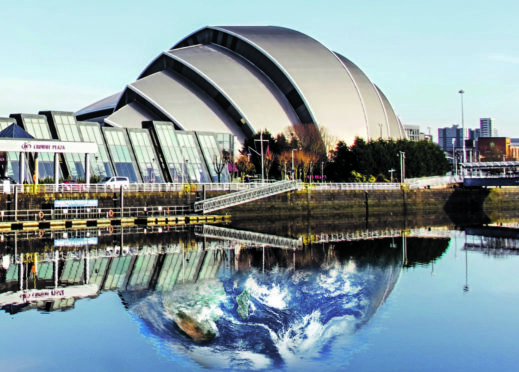

Our report triggered a global debate among marine biologists and environmental campaigners, including experts at the CPR, which has been studying plankton in the north Atlantic for 70 years with its results informing international policy makers.

Johns does not believe oceans are as close to a tipping point as the Goes data suggests but believes we ignore plankton at our peril. The CPR’s work on behalf of UK, European and North American governments shows plankton populations facing evolving challenges posed by climate change as CO2 both warms the oceans and turns them more acidic.

Off Britain’s coastline, many types of plankton have headed towards the Arctic in search of colder temperatures. Johns said: “Most of the time, what’s happened is they’ve just simply moved northwards, which is fine for them for the moment because there’s somewhere for them to go. But if the water warms much more there will be problems.”

He added: “In UK waters, there have been some winners and some losers. Some of the critically important plankton, they like cold water so they’ve shifted northwards. But other species have shifted in from the south to replace them, though not always in the same numbers.

“Are we in a situation that requires mitigation as a matter of urgency? Yes, I would say so. If they carry on moving north and run out of water, if the seas become too warm, then we’ll lose a lot of those types of plankton that are critically important for fish species and marine mammals.”

Goes identified the loss of plankton as an existential threat as, without it, the oceans’ food chain would collapse. Dryden suggested the tipping point could arrive within 25 years unless there is action to curtail the toxins dumped into the seas from plastics, chemicals and farm fertilisers.

But Johns, who has offered to collaborate with Goes on its future data collection, suggested the conclusions of the recent research were excessively pessimistic: “It presented a doom-and-gloom picture, almost like it was too late to do anything, and that’s not true. There is a large group of scientists and governments involved in studying plankton and nobody could ignore such a drop. From the results we’re finding, we’re not at that point at the moment and won’t be for a while.

“But what needs to be done to change the long-term trend? That’s the million-dollar question. That’s the work we’re all involved with.

“Temperature rises associated with climate change is the big one. I’d definitely focus on reducing CO2. The take-home message is that people should really care about what’s going on in the sea, particularly plankton.”

The CPR has plankton-monitoring equipment being towed across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by up to 30 vessels at any one time, generating 5,000 detailed samples every year.

Goes welcomed the chance to collaborate with the CPR and Diane Duncan, a co-author of Dryden’s report, said: “We need to bring forward policies that would see ocean pollution dramatically reduced through investment in green chemistry and waste water treatment around the world. For all our sakes, let’s hope we can now get on and clean up our oceans and let them be rewilded.”

Setting out from Scotland, the crew of Goes’ yacht Copepod sailed along the French and Portuguese coasts before crossing the ocean and continuing work in the West Indies. In addition to its own samples, Goes provided equipment to other sailing boats so they could perform the same trawls and report back with their results.

The team has compiled and analysed information from 13 vessels and more than 500 data points. Now they have alerted the scientific community to their analysis and are appealing for others to carry out their own tests to bolster the research.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe