IT was only one week, a few summer days spent at an outdoors camp in the Perthshire countryside.

But, fifty years on, Bill Jones has never forgotten his time at Cultybraggan or the feeling of a haunting darkness he found there. He doesn’t think he ever will.

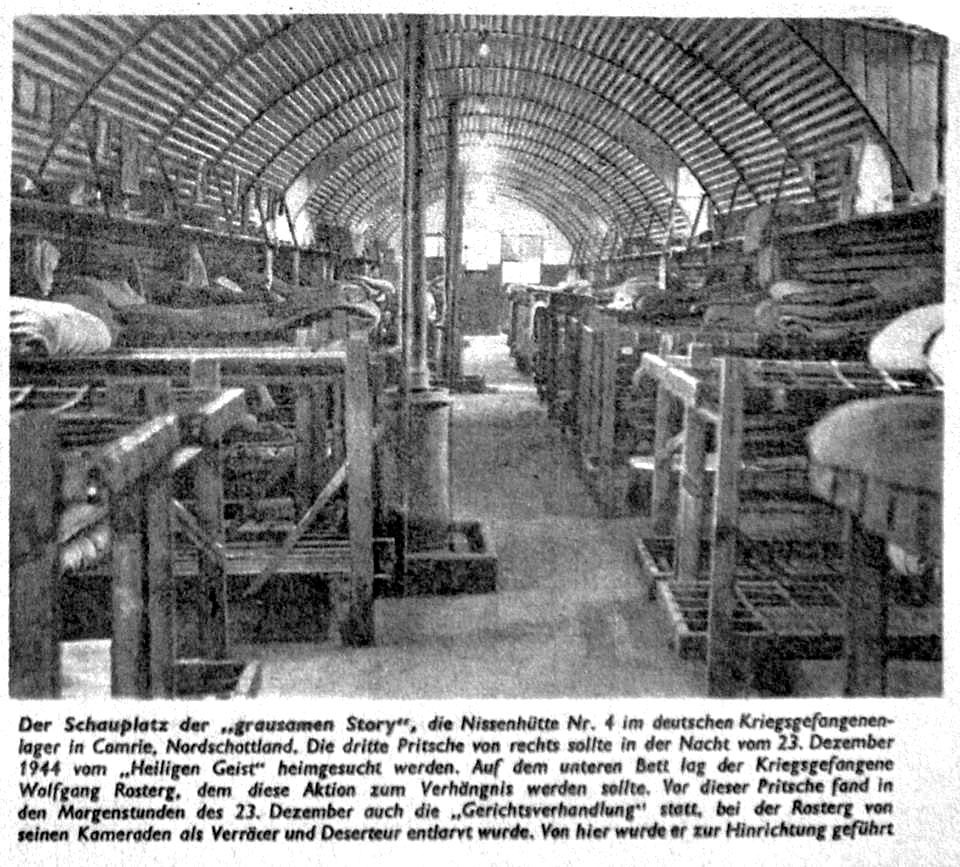

He was one of thousands of children to bunk up in the camp’s Nissen huts in the decades after the Second World War, years after the huts had housed Nazi prisoners of war, soldiers notorious for their fanatical loyalty to Hitler.

Now, Bill’s time at the camp in Comrie, Perthshire as a 14-year-old schoolboy in 1968 has inspired his novel, Black Camp 21. The award-winning writer, who revisited the camp to unearth one of its darkest secrets, said: “I remember it vividly. We spent the days running around, getting lost in the mountains and nights gathered round the campfire with the transistor radio, listening to The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Aretha Franklin.

“We slept in bunks in one of the huts. It was fun, but the camp was a bit creepy. We all felt it and were a bit uncomfortable. It was as if it was haunted. We asked about the history but nobody told us. When the week was over, none of us was sorry to leave. Now I know why.”

A few years ago, Bill, 64, came across a picture of Cultybraggan and the memories came flooding back.

Still keen to find out about it, he started researching. And what he found out about Camp 21 – its official name during the Second World War – was shocking.

Few people today are aware of the huge number of German prisoners housed in more than 600 ad hoc camps across the country from 1944 onwards.

By the end of the war, it is thought up to 400,000 soldiers had been shipped across the Channel to see out the war in Britain.

Among them were 70,000 category “black” prisoners – the diehards sworn to fight for the Fuhrer until the death. Camp 21 housed 4,000 of the most dangerous veterans of the SS, soldiers refusing to believe Hitler’s awful dream was over.

In December 1944, one of them, German officer, Wolfgang Rosterg, was beaten to death in Hut No 4.

The following year, five of his fellow prisoners were hanged for his murder at Pentonville Prison.

Intrigued by the story and why it happened, Bill spent three years researching Rosterg and Camp 21.

He said: “It was one of the most horrific non-combat stories of the war – and a completely unknown part of it.

“And if I’d known all about it when I was 14, I wouldn’t have slept for a week. Or maybe a year.” For the former journalist turned TV documentary maker, finding the basic information was easy.

Digesting it was a little more difficult.

He uncovered original letters, records of the trial and found transcripts of secret interviews taped with soldiers – the lost voices of the German troops.

In fact, Bill was so disturbed by the death of Rosterg that he went to find his grave in Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery in the East Midlands.

“It’s where all the German servicemen who died in Britain but weren’t taken home were buried,” he said. “Nobody seems to know much about that either.”

Next to Rosterg’s grave was that of another Camp 21 casualty, Oberleutnant Willy Thorman, who’d been found hanging from a tree just a week before Rosterg’s killing.

“It was a pretty brutal place,” Bill said. “Really the blackest of the black camps.

“For any writer, nothing beats the sensation that one is covering new ground, or covering old ground very differently. Tell almost anyone that more than 400,000 German prisoners lived in Britain for up to four years, and they will be amazed.

“Tell them there was probably a POW camp in their town and they probably won’t believe you.

“It felt like the book I had to write, something I was destined to do, the story I was meant to tell.”

Bill, from North Yorkshire, discovered lots about Rosterg – but struggled to understand why he had been killed.

“We know he was older than his fellow prisoners, was well travelled, spoke numerous languages, was a successful businessman, and his job – which links him to the manufacturers of Zyklon B, a chemical which was used in the gas chambers – marked him as an outsider.

“It’s easy to imagine him being dangerously vulnerable to the paranoia of his fellow prisoners.

“The fact that he wasn’t SS, took a doubtful view of Hitler’s war and an openly sceptical one which would certainly have contributed to his unpopularity and that his skill in languages granted him privileged access to senior German and British officers, could have raised suspicion that he was a mole.

“Whether he was or not will forever remain unknown.”

The mystery formed the basis of Black Camp 21, which tells the story of real people, alongside fictional protagonist Max Hartmann, who is categorised as a “black” prisoner and shipped off to a place where he can do no more damage.

Bill, who has already published two biographies, added: “Writing my first novel has been a challenge, and it’s a bit of a waiting game to see how it will be received.

“At least with a documentary, it goes out at 9pm, and by 10pm you know how many millions watched it.

“With books, it’s different. There’s not that same adrenaline rush – but I hope it’s one people want to read.”

Most of the POW camps in Britain were demolished – but Camp 21 still stands the same as it did in 1944.

“If you close your eyes, you can hear the German voices and the gunfire,” Bill said.

“It’s one of the most amazing relics I’ve ever come across and is now a listed building. With any luck, my book will inspire people to come and see it for themselves.

“There is a gripping tale behind it – but that’s what makes it such an amazing place.”

Black Camp 21, published by Polygon, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe