ALASDAIR GRAY has been to hell and back after a fall that left him unable to walk but he insists he will complete an epic version of Dante’s Inferno.

The acclaimed artist and novelist, who has just celebrated his 83rd birthday, is working around the clock to finish his version of the 14th Century poem that described Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s journey through the mythical nine circles of hell.

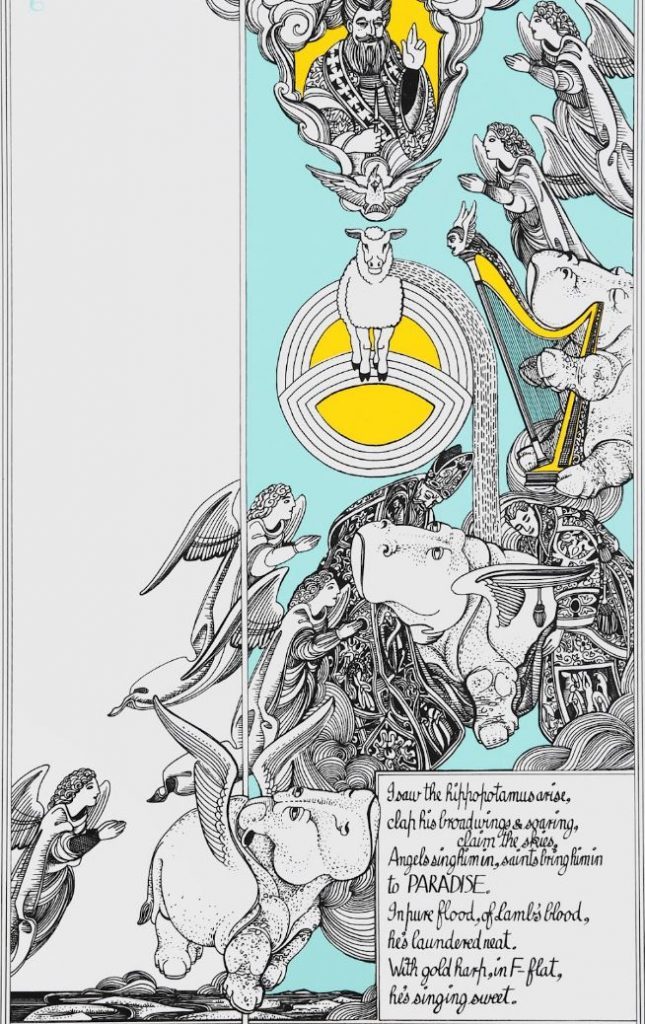

Gray’s English translation will be illustrated by his distinctive artwork but the task is all the more impressive as he has been wheelchair-bound since a fall in 2015.

Defiant Gray told The Sunday Post: “I’ve been lucky to finish a great many pictures and a great many books and there are still some to come.

“I’ve got more work to do. I’ll finish my translation or my English paraphrase of Dante, which will be coming out over the next three years when I finish the illustration elements.

“The words for it are finished.

“Canongate have applied to Creative Scotland to see about getting money to pay me to work upon the illustrations for the book, so that I don’t need to stop and work at other jobs. That’s the set-up.”

Gray, who was hospitalised for six months following his fall, is also battling back to fitness in order to take part in one of his largest projects, a mural for the exterior of the Scottish Parliament.

It is currently in the planning stages.

“I am working on sketches in connection with the mural for Holyrood that I am collaborating on with my good friend, the artist Nichol Wheatley,” he said.

“The mural will be a panoramic view of Scotland itself viewed from east to west.”

Last year, Gray held a rare retrospective exhibition of his artworks at Glasgow’s Hidden Lane Gallery, which provided him with an opportunity to look back on his life and career.

He is best known for his 1981 novel, Lanark, which has never been out of print, and has been described as a landmark in 20th Century fiction.

Yet he refuses to entertain suggestions that his debut literary work, which was recently adapted for the stage, is one of the greatest Scottish books of all time.

In fact, he doesn’t even think it is the finest Glasgow work, choosing an 1822 story by John Galt, The Entail.

“I would disagree with critics who say my book is the great Glasgow novel. I can see why a lot of folk might think Lanark is it, but there’s others,” said Gray. “The great Scottish novel of course, is Confessions Of A Justified Sinner, but there’s a hell of a lot of good Scottish writers.

“If you take into account that we have Robert Louis Stevenson and Walter Scott we punch as much weight as the Irish, but the English find it hard to believe.”

Gray began writing Lanark while studying at Glasgow School of Art, in 1954, and finished it in 1976.

“I was vain enough to think that one day it would be a book that the world would not willingly let die, but I did not think so many critics would speak approvingly of it so soon as they did,” he said.

“I was very pleased with the reaction.

“I thought it would take a while for the critics to appreciate it. One of the first editors who decided his publishing house would take it wasn’t sure if it would be a bestseller, but he thought it would be a cult success in the United States.

“I thought, aye, you’re probably right.

“It turned out not to be a best-seller, but it has been a seller for many years.”

Asked whether there were autobiographical aspects of the main character in Lanark, Gray joked: “Oh, yes. It uses bits of my life, but it’s not purely autobiographical.

“I was making notes about my life, whether at school or art school all the time and seeing ways to twist them towards the tragic.

“My hero fails his art school exams. He fails this, he fails that and actually I failed none of it.

“Unlike my main character I never went mad and committed suicide.

“I can only promise you that this is the case.”

He puts his achievements down to the success of the fledgling welfare state in place when he was a boy.

“I think I’ve been allowed to do a lot more and I was unusually lucky,” he said.

“I was born into the welfare state when it was in full working order.

“It was set up during the Second World War as a result of the Beveridge Report.

“As a result I belonged to a very lucky generation of Scottish artists who got further education.

“The poet Tom Leonard, the storywriter Jim Kelman, the poet Liz Lochhead; there were a hell of a lot of us who were lucky and I feel very sorry for the post-Thatcher lot, who were folk from working class backgrounds who came after a time when Scottish secondary education was superior in general to the English equivalent. It gave us a start in life.”

Reminders of his life’s work have added to his determination to get back on his feet in 2018. He has not quite given up hope of being able to walk again.

Gray insists he will not be held back as a result of the injuries sustained during the fall, though he admits he is a long way from a clean bill of health.

“I haven’t much recovered from the accident,” he said.

“I was going home one night and I can’t understand how it quite came about, but I left the taxi, climbed the stairs, put my key in the front door and found I had somehow fallen and broken lower vertebrae.

“What puzzles me is that I had kind of fallen backwards and was lying on the steps. I don’t understand how it happened.

“With physiotherapy, I might learn to at least hobble about with crutches, but I haven’t had that training.

“I rather think the National Health Service has given up on the idea of giving people to waste time on me.

“So I may have to pay money myself to get extra physiotherapy.

“I have written to my hospital consultant to ask if there’s a way of self-registering and he has responded with a questionnaire to fill in and tick boxes.

“I have every expectation of dying in working order and who can be luckier than that?”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe