The world is in turmoil and huge, urgent challenges are hurtling towards a new Labour government and its nervous, untested ministers.

Abroad, the devastation left by war and revolution is everywhere. At home, the economy, industrial unrest and a housing crisis demand immediate attention while the future of Scotland is a fractious, relentless debate.

Coping with a hostile press and internal divisions, the inexperienced administration will endure a torrent of unforeseeable events and scandals, from fears of Russian intervention in UK elections and fake news to claims of cash for honours and scrutiny of the prime minister’s personal finances.

On January 22, 1924, Britain’s first Labour government took charge and an authoritative new account of its 10 hectic months in office is likely to give Sir Keir Starmer, the party’s current leader, shocks of recognition, trepidation and anticipation.

The Wild Men, written by David Torrance, is a compelling account of the first Labour administration led by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and how, as the author notes, paraphrasing American writer Mark Twain, “history might not repeat but it rhymes”.

Torrance, a writer, historian and House of Commons researcher, said: “When I started, I expected to discover a faraway country that might not make a lot of sense seen from today but I was struck by the parallels. The issues and controversies then seem very familiar now.

“The politics of any particular country is likely to throw up the same issues over the years but even the language being used by these politicians from 100 years ago seems resonant today.”

Torrance, a former political journalist in Scotland, believes history has lessons for everyone, not least politicians. He said: “There is nothing new under the sun and history can be enormously important for informing the present, particularly in politics.

“There is clearly value in looking at how earlier governments handled very challenging situations and that first Labour government had more challenges than most.”

The first Labour government

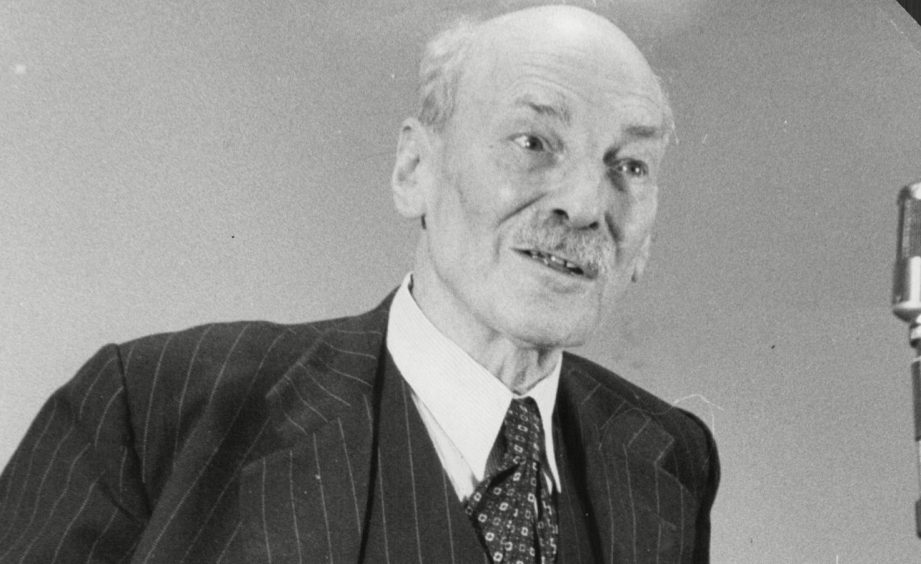

It was led by MacDonald, who was often difficult, sometimes devious but absolutely determined to show Labour was, indeed, a party of government.

A prickly workaholic, he may not have been a perfect politician but, according to Torrance, his mistakes should not obscure a transformational role in British politics.

Political parties are built on their heritage but, Torrance believes, the place of MacDonald in Labour history has been unfairly shaped by the infamous “Great Betrayal” of 1931 when he formed an alliance with the Conservatives.

“There could be a little more generosity, I think but it is not uncommon for prime ministers to be remembered for just one thing, often a mistake towards the end of their careers,” he said. “History can be brutal.”

Scouring the archives and diaries of a century ago, Torrance found MacDonald an impressive figure, despite his flaws, with great political skills.

He said: “The fact that he got that minority government together and sustained it for almost a year with just 191 MPs is a quite remarkable achievement.”

January 22, 1924 – the day Labour took power for the first time – was the opposite of a slow news day as billboards for the evening papers confirmed: “Lenin dead (official) Ramsay MacDonald Premier.”

MacDonald, still bereft by the sudden death of his wife from blood poisoning, would write in his diary: “The load will be heavy and I am so much alone.”

For the months ahead, when his reputed 18-hour working days would lead to what Torrance suspects was some kind of breakdown, MacDonald steered a government which, despite being new to power, was one of achievement, putting in train policies that would change Britain forever. Torrance said: “There are plenty of governments with more MPs and longer terms that have achieved less. They packed a lot in and begin a lot of things carried on by future governments.”

The title of his book – in full, The Wild Men: The Remarkable Story Of Britain’s First Labour Government – is inspired by a letter to The Times from a former Conservative MP railing against the voters who had propelled the people’s party into power for the first time; “the communists, the wild men, the work-shy, the ignorant and the illiterate.”

The Cabinet seem initially less wild than bewildered by the sartorial demands of meeting the king but, realising their grip on power was weak, as a minority government relying on the Liberals for support, their leader had one ambition: to prove Labour, given the chance, could govern. He achieved that, Torrance believes, not least because of his decision to become Foreign Secretary as well as Prime Minister.

“He realised that handling foreign affairs well would reinforce the perception of good, competent government and, in that respect, he succeeded extremely well. Within months, he was seen as the undisputed leader on the world stage.

“He suspected voters had, until then, thought only aristocratic Liberals and Tories could do that because they had the airs and graces but this illegitimate son of a farmhand and housemaid showed his grasp of world affairs was every bit as good, if not better.

“In terms of demonstrating that Labour was fit to govern, that played a huge part.”

A working-class cabinet

The ministers assembled by MacDonald remains Britain’s most working-class cabinet. There may have only been one woman – the party had just three women MPs after the 1922 election – but the Cabinet was drawn from across Britain and most were former manual workers, including three miners.

Scots were everywhere, from MacDonald down, but perhaps his most-celebrated minister was John Wheatley, an adopted Glaswegian. His people skills and political savvy allowed Wheatley, Irish-born but one of the most influential Red Clydesiders, to drive through a massive house- building programme despite only becoming an MP a little more than a year earlier.

That house-building programme may have done most to prove Labour could be a party of both vision and competence in government but Wheatley’s colleagues also took important steps towards the National Grid; new transport links, including the first road joining Edinburgh and Glasgow; and a more generous benefits system.

Abroad, meanwhile, MacDonald’s short but acclaimed stint as Foreign Secretary was instrumental in forging a more solid peace between France and Germany and new relations with revolutionised Russia.

The government became a victim of its own success, however, when, after MacDonald turned a political drama into needless crisis, Liberal jitters about being supplanted as the main progressive party saw the first Labour government voted down in November, just 10 months after it began.

The party’s time in government would, however, pave the way for its return to power in the years to come, and today, as another election looms, many observers suggest the only remaining unanswered question is the size of Labour’s majority.

Aghast at any hint of complacency, Sir Keir Starmer might still take some secret inspiration from his party’s first prime minister’s typically understated diary entry exactly 100 years ago: “Without fuss, the firing of guns, the flying of new flags, the Labour government has come in.”

Fake news and controversy have been the bedrock of politics for decades so why would today’s be any different?

International tension and economic uncertainty backdropped the first Labour government and, potentially, the next.

Away from politics, however, Ramsay MacDonald and his ministers endured controversies and scandals that also seem thoroughly modern.

Media scrutiny of the prime minister’s personal finances did not begin with Boris Johnson, for example, and MacDonald’s unusual financial arrangements were exposed after reporters uncovered a secret loan from Sir Alexander Grant, the Scots tycoon behind McVities and inventor of the digestive biscuit.

The men had been lifelong friends, with Grant, from Forres, growing up not far from MacDonald’s childhood home in Lossiemouth. When MacDonald entered Downing Street in January 1924, Grant quickly offered a £40,000 loan and a Daimler car to bolster the salary of a prime minister then earning £5,000 a year and still using public transport.

When exposed in the press, the loan looked bad enough but Grant, a well-known philanthropist, had soon after become a baronet in the King’s birthday honours making the scandal even more malodorous with a whiff of cash for honours.

Historian David Torrance, author of The Wild Men, charting the first Labour government, said MacDonald’s reputation for sanctimony was a red rag to journalists pursuing his perceived hypocrisy: “If it had all been made public at the time, it would probably have been fine. The mistake was keeping it secret and MacDonald realised that. He knew it could blow up in their face and, inevitably, it did.”

Meanwhile, the next Labour government is likely to face the same fears of foreign interference in UK elections and fake news as the first.

Days before the election in 1924 that ended Labour’s first term in office, the Daily Mail published a letter apparently written by Grigory Zinoviev, president of the Communist International, urging Labour to help foment revolution in Britain.

The letter was a fake but, with the violence of the Russian revolution fresh in voters’ minds, still caused uproar.

Torrance said: “Today, we are exercised by Russian disinformation and interference in our elections but here is a direct and dramatic precursor.

“Like today, it played on voters’ fears because the consistent charge from Labour’s opponents was that however moderate it tried to appear, it was taking orders from Moscow.

“This was, apparently, the proof when, in fact, it was absolutely fake news.”

Labour’s leading men: Three who became PM

Since 1900, when Labour was formed, the party has only won eight out of 32 general elections. And in the 124 years since the turn of the last century, only three Labour leaders have won outright majorities.

Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee was Labour’s first leader to win a majority in a general election, in the landslide victory of 1945.

His achievements included the creation of the welfare state and the NHS, nationalisation of coal mining, steel industries, the railways, the Bank of England, civil aviation, electricity and gas, and the building of one million homes.

But in the 1950 election, Labour only won with a majority of five. A snap election the following year led to 13 years of Tory rule.

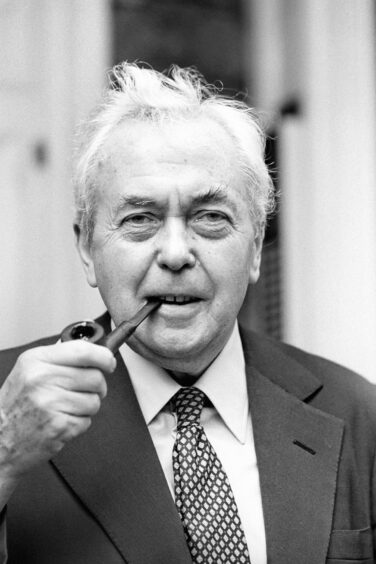

Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson won three general elections for Labour, in 1964, 1966 and 1974. He abolished capital punishment, decriminalised homosexuality, relaxed divorce laws, liberalised abortion law and ended theatre censorship.

He also promoted with passion his commitment to “the white heat of technology”, asserting that scientific progress was the key to economic and social advancement.

Tony Blair

Tony Blair won three consecutive elections with large majorities, in 1997, 2001 and 2005, making him Labour’s longest serving PM.

His achievements include the establishment of a national minimum wage, civil partnerships for gay people, an independent police complaints commission, devolved governments for Scotland and Wales, a big expansion in higher and further education and cutting NHS waiting lists.

He also introduced the Freedom of Information Act and the Human Rights Act, enabling citizens to have alleged abuses of human rights heard in British courts.

The Wild Men: The Remarkable Story Of Britain’s First Labour Government by David Torrance is published by Bloomsbury Continuum

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Daily Mail/Shutterstock

© Daily Mail/Shutterstock © ANL/Shutterstock

© ANL/Shutterstock © PA Wire/PA Images

© PA Wire/PA Images © Toby Melville/PA Wire

© Toby Melville/PA Wire