An academic and designer pioneering the use of jewellery as an identification tool is helping trace the families of migrants killed as they tried to reach Europe.

Dr Maria Maclennan, thought to be the world’s first forensic jeweller, is one of a team working to identify unclaimed bodies on the border between Greece and Turkey by studying rings, necklaces and other belongings.

About 2,000 migrants have lost their lives in the struggle to cross the Evros River. Jewellery is often one of the few belongings capable of helping identify them with Maclennan’s work focuses on features such as engravings, inscriptions, serial numbers and microscopic markings on gemstones, bracelets, rings, necklaces and watches which, she says, can often link the piece to a specific jeweller or geographical location.

The route through Turkey into Greece is seen as a key way into the European Union for migrants escaping wars in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan.

Maclennan, a lecturer in jewellery and silversmithing at Edinburgh University who also works for Police Scotland, said: “We are working to document and photograph more than 500 items recovered with the deceased along the Evros River, commonly known as the River of Death.

“It is a particularly treacherous migratory route between Turkey and the north of Greece.”

One of the aims of Maclennan’s latest project is to build an online catalogue of personal effects, and is the first of its kind dedicated to missing migrants.

She added that the catalogue would launch later this year and was connected to more than 100 missing migrants. “It will bring visibility to erased identities and enhance opportunities for identification,” she said.

Including photography and storytelling techniques, she hopes the catalogue will provide a much-needed tool to help support the identification of those who lost their lives.

“We hope the project will provide a unique opportunity to bring together experts from a wide range of disciplines to help contribute to the creation of investigative leads,” said Maclennan.

“We will be arranging a series of design workshops with experts in both Scotland and Greece, as well as online and also hope to eventually produce an accompanying book.”

Maclennan believes expertise acquired from the project can be passed on to countries where specialist knowledge in the area is limited.

After studying jewellery at art college, Maclennan worked with designers, forensic anthropologists and police officers during her masters degree on a project at Dundee University’s renowned Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification. This involved working on a jewellery database classification system to assist victims’ families trying to describe individual items.

Her work in Greece is funded through an Economic and Social Research Council Impact Acceleration Award and is the result of a collaboration involving herself, forensic pathologist Professor Pavlos Pavlidis, and forensic anthropologist, Dr Jan Bikker.

Pavlidis, based at Alexandroupolis General Hospital in Evros, Greece, has work spanning more than two decades and has examined the bodies of more than 430 deceased migrants. His university hospital is the largest on the Greek side of the river and its forensic department receives all of the retrieved bodies found by Greek authorities.

Human remains expert Bikker works with the Platform for Transnational Forensic Assistance Forensic Missing Migrants Initiative, a charitable organisation that works to raise awareness of the significant barriers to identifying missing migrants across the Mediterranean. It also provides support to grieving families of the missing.

Rolex murder: How victim’s watch led police to killer

One of the first cases revealing the potential of jewellery to aid investigators involved a mystery body dumped at sea and an expensive Rolex.

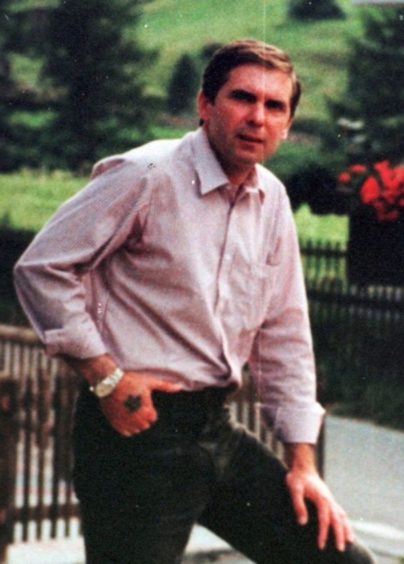

Ronald Platt accompanied his friend, Albert Walker, on a fishing trip in July 1996. But it was to end in murder when Walker killed him and threw him overboard.

In a bid to make sure the body was never found Walker tied an anchor around his victim’s body thinking it would decompose at the bottom of the sea.

However, Mr Platt was hauled out of the English Channel two weeks later by trawlerman John Copik and although his body was too decomposed to be identified, the Rolex Oyster Perpetual watch was still in good order and was used to identify its owner and secure Walker’s conviction.

Police were able to determine the date of death by examining the date on the watch calendar. As the Rolex movement had a reserve of two to three days of operation when inactive, and was fully waterproof, they were able to pinpoint the time of death to within a small margin of error.

A meticulous search through Rolex’s records then confirmed Platt as the owner.

Jigsaw analysis of Walker’s whereabouts on the day of the murder helped prove his guilt and he was jailed for murder in 1998.

In his haste to cover his tracks Walker failed to realise the watch would lead police straight to him.

In an unrelated case, jewellery found on the body of a murdered teenager helped identify her five months after she went missing.

Shafilea Ahmed, 17, disappeared from her home in Warrington in 2003. Her body was later found in the River Kent in Cumbria. She was identified using a gold zigzag bracelet and blue topaz ring discovered on her remains.

Her parents, Iftikhar and Farzana Ahmed, in 2012 were convicted of her murder and jailed for life.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe