HER taste for good food is equalled only by her thirst for uncovering family history.

So when Mary Contini, best-selling author of series of books about Italian life and cooking, rescued a dusty old pile of family notes set for the rubbish tip, it provided the ingredients for a new book about love, loss, new beginnings – and, of course, great food.

Dear Alfonso is a two-pronged epic that tells the story of Mary’s father-in-law, Carlo Contini, and his journey of survival from war-torn Italy to Edinburgh, and the tale of his father-in-law, Alfonso Crolla, who co-founded the famous Edinburgh delicatessen, Valvona & Crolla.

It’s an adventure full of war, poverty, love, loss and overcoming the odds, but at its heart is a tale of how food is the glue that keeps a family together.

“Carlo’s story is one about food and enjoying it,” said Mary, who is director of Valvona & Crolla.

“The point of the story from my perspective is how the family managed to survive when they had very little food during the war. They learned not to waste and the food was shared between family and neighbours – whoever needed it.

“I feel there’s a movement in Scotland just now where some of the younger generation are more canny about how they use food and also more aware of where it comes from.

“People are becoming more conscious of local, seasonal food, and are waiting for the spring raspberries or the first lambs of the season.

“I don’t know if it’s awareness of global warming, the effects of excess or not wasting money, but there’s a real mood and awareness in Scotland just now towards food and I think it’s amazing.”

But Mary, who was brought up surrounded by family members cooking, believes we are letting ourselves down by not teaching children to cook.

“It’s one of the issues I believe still has to be corrected in society,” she continued.

“If youngsters knew simple things like how to boil an egg or make soup, it would give them a basic element of survival and health for when they’re older, but if you don’t provide those tools, they’ll end up going on to buy ready meals.

“I always point out that it can cost £3 for a jar of pasta sauce, but just a quarter of that for a tin of tomatoes, garlic and olive oil to make your own.

“Annunziata, Carlo’s mother, said that when people got fridges in their homes, that’s when they started buying more than they needed and stopped sharing. If we didn’t buy so much to store, we wouldn’t waste so much.”

There’s a feast of recipes in the book that come straight from Annunziata’s larder, collected from the cousin of Mary’s husband, Philip, in the family home of Pozzuoli, near Naples.

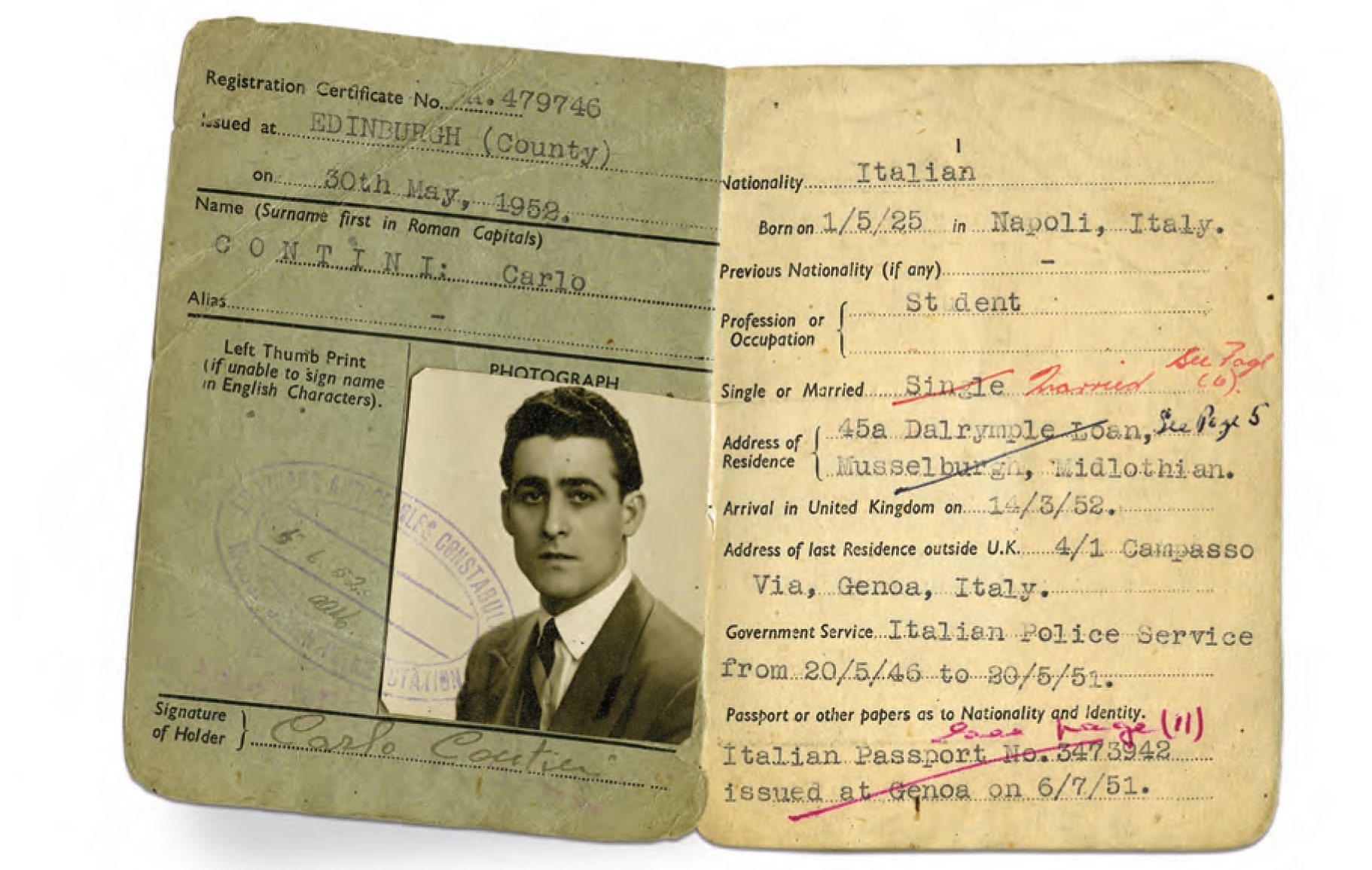

Carlo was born in the fishing town in 1925, but much of what transpired between that date and his arrival in Edinburgh in 1952 – where his proposed three-month stay to learn English was extended when he met Olivia Crolla – remained hidden until Mary discovered the notes after he died.

“My previous book, Dear Olivia, was 10 years ago and people were always asking what was next,” said Mary, who is mum to Francesca, 36, and 22-year-old Olivia.

“Carlo wanted to tell his story but he spoke in his own dialect, so Philip and I asked him to write it out. But then he became very ill and passed away three years later. Seven years after that, Olivia died.

“The idea had gone out of my head, but as we were cleaning out the house we found a box of papers that were going to the dump.

“There were 35 pages of memories, written in his dialect, which I had a university student translate. We knew he was a 28-year-old policeman when he arrived in Edinburgh in 1952 and that he discovered he was adopted shortly before marrying, but there was so much more we didn’t know about that he had written down.”

Details like his first job at just seven years old applying the polish to coffins, being sent to Genoa to work in a munitions factory when he was only 15, and the poverty, starvation and terror inflicted on his family back in Pozzuoli.

“We didn’t know about the drama they faced during the Second World War, how dangerous it was and how starved they were.”

Dear Alfonso, published by Birlinn, also touches on the way the popular Italian community in Scotland were turned on after Mussolini sided with the Germans against the Allies.

Alfonso was one of many “enemy aliens” arrested and deported from his adopted homeland in the aftermath. He drowned as a prisoner of war when the Arandora Star was sunk as it made its way to Canada in 1940.

From that first wave of Italian immigrants who came to Scotland in the early 20th Century, there is now thought to be around 250,000 people in the country who identify as being Italian.

Mary believes they have not only integrated into, but added to, the Scottish way of life.

“Italian food has had such an influence on Scots,” she said.

“Who hasn’t had ice cream, fish and chips or pizza? Or which household doesn’t make pasta twice a week? When the Italians first came to Scotland they were different, but soon became part of the culture.”

Mary is a second generation Italian, brought up in Cockenzie, East Lothian, along with her seven siblings, above her grandfather’s ice cream and fish and chip shop.

Her dad ran three cafes; catering for the local clubs, like the working men’s, in winter.

Like Carlo, she worked from an early age, going with the kiosks down the east coast selling ice cream from the age of eight or nine.

It’s the only life she’s known and she wouldn’t change it for the world. And now life has come full circle for the grandmother of two.

“Little Alfonso, or Alfie, is five now and he thinks the shop is his,” she laughed. “He comes running right round to the other side of the counter when he visits!

“He’s quite chuffed as well, because he thinks the book is named after him. My next book will have to be called Dear Florence, for my granddaughter!” Until then, she’ll continue to follow the recipe that has made life bellisimo.

The recipes

Mary first met Carlo’s mother, Annunziata, while she was on honeymoon in Italy in September 1979.

She describes her grandmother-in-law’s cooking as revelatory.

“From a tiny scullery, she managed to feed all of her family, up to 20 people twice a day, and with a magical enthusiasm and alchemy she introduced me to the most flavoursome, exquisite and mouth-watering food I had ever tasted,” Mary explained.

“She had no concept of ‘food waste’. Every morsel was shared among too many mouths.”

Spaghettini Sciuè Sciuè

In Neapolitan, sciuè sciuè means quickly, in a hurry. Fast food for Annunziata was having something ready when Carlo came home late from a visit to the cinema or taking a girl to a dance.

Serves 2

- 180g spaghettini

- Sea salt

- Extra virgin olive oil

- 2 garlic cloves

- Ripe plum tomatoes

- Basil leaves

Add a large handful of spaghettini to a pot of boiling salted water.

Stir to make sure they are well loosened in the water.

In a wide frying pan warm four to five tablespoons of extra virgin olive oil and add the garlic cloves cut into slivers.

Wash four to five very ripe plum tomatoes and, using your hands, squeeze them into the frying pan, discarding the skins and seeds left in your hands.

Cook on a brisk heat and season well with sea salt.

Tear in plenty of fresh basil leaves and, before the pasta is cooked, use a fork or tongs to transfer the pasta dripping with the cooking water into the frying pan to finish cooking.

Ready by the time Carlo has climbed up the 178 steps home.

Limonata

Home-made lemonade

- 1 litre cold water

- 175g granulated sugar

- 2–3 Amalfi unwaxed lemons

- Fresh mint or basil

Make a sugar syrup by adding half of the cold water to the granulated sugar.

Bring to a simmer and once the sugar has dissolved, boil for 10 minutes to make a syrup.

Add the rest of the water.

Wash and zest the lemons and then, after warming them in your hands, squeeze them to collect about 100ml of juice and pulp.

Add this to the syrup and check the flavour, diluting as required.

Refrigerate for about four hours to chill.

Serve with some cubes of ice and some fresh mint or basil leaves.

Pesto Alla Genovese

Annunziata made trofie pasta – small cigar-shaped rolls of homemade pasta – and served them with a type of pesto, invented from descriptions of the green sauce Carlo described to her when he returned from Genoa.

Use the freshest small basil leaves for the most intense flavour. Always use freshly-grated pecorino and leave the final pesto coarsely textured to enhance its flavour.

- 100g fresh basil leaves, no stalks

- 1 tablespoon pine nuts

- 6–8 tablespoons Ligurian or a light extra virgin olive oil

- 2 cloves new season garlic

- 2 tablespoons fresh grated pecorino Romano

- Sea salt to taste

Put the basil leaves, pine nuts and a pinch of salt on a wooden board.

Use a mezzaluna or a heavy knife to gradually chop the leaves and nuts together, adding small amounts of leaves at a time.

Put the resulting paste into a bowl and add the grated cheese, and, after mixing everything, incorporate the oil to create a textured pesto.

Taste and add some salt as necessary.

So what if it takes a bit longer?

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe