HE’S the forgotten artist who became the first European to paint the far side of the world.

Sydney Parkinson joined the crew of Captain Cook’s famous expedition to the South Pacific and sketched hundreds of plants and animals never before seen in the West.

He was probably the first Scot to see a kangaroo, certainly the first to draw one, and broke more new ground by getting a tattoo in Tahiti. He was remembered last week in a special set of Royal Mail stamps celebrating the 250th anniversary of Cook’s expedition.

His work in the South Pacific has been hailed as an invaluable treasure trove of information about the uncharted lands of Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific.

But the Edinburgh-born illustrator did not make it back home.

On August 25, 1768, Captain James Cook set out on what would prove to be a perilous voyage.

Officially, the trip was launched to observe the transit of the planet Venus in the night sky, and to find evidence of Terra Australis Incognita – the unknown southern land.

They were to collect as much scientific information as possible, and observing and recording the natural world was vital.

Parkinson, a talented botanical artist, was asked to accompany Cook’s naturalist Joseph Banks as his draughtsman, and the Scot – aged only 22 – agreed.

“He proved to be a diligent member of the crew, and accounts from his shipmates say Parkinson was respected and well-liked,” said Alwyn Peel, secretary of the Captain Cook Society, who studied Parkinson’s role in the expedition. “A young Quaker from Scotland and only 22 at the commencement of the voyage, he was described by Joseph Banks as an ingenious and good young man.

“He was virtuous, eager and youthful and must have become quickly well known to the rest of the crew during the voyage.”

An adventurous streak came to the fore before Cook’s vessel, the HMS Endeavour, reached the Pacific. The Endeavour stopped at Brazil, where the local governor forbade them from docking for diplomatic reasons.

Upset at being denied the chance to study the rich Brazilian rainforests, Parkinson and several others launched midnight expeditions in a dinghy to the South American mainland. There they collected – and drew – samples of unfamiliar flora. Cook never discovered the covert trips – which was just as well, as they risked causing a major diplomatic incident.

The crew reached Tahiti in Hawaii, where they met locals – and Parkinson, writing in his journal, was impressed by their kindness.

“The people in the canoes were of a pale, tawny complexion, and had long, black hair,” he wrote. “They seemed to be very good natured, and not of a covetous disposition; giving us a couple of cocoa nuts, or a basket of apples, for a button or a nail.”

And later he wrote about natives visiting the Endeavour with “bananas, cocoas, breadfruit, apples, and some pigs”.

There were few new plants for them to draw, but Parkinson set to work on completing the sketches he had made.

His work became twice as difficult when the only other artist taken on the trip suffered an epileptic fit, fell into a coma and died.

The job of artist fell onto Parkinson’s young shoulders – but he thrived under the pressure, with his colleagues reporting he sketched the wildlife almost as quickly as they could find it.

It was in Tahiti where the artist and some of the crew observed the islanders’ habit of tattooing their bodies.

The word tattoo in fact comes from Cook’s expedition, and he noted how some of his men couldn’t resist trying it for themselves.

That included the bold Parkinson, who became one of the first recorded Scots to ink his skin – an intricate design painfully inscribed onto his arm with a sharpened bone dipped in blue dye.

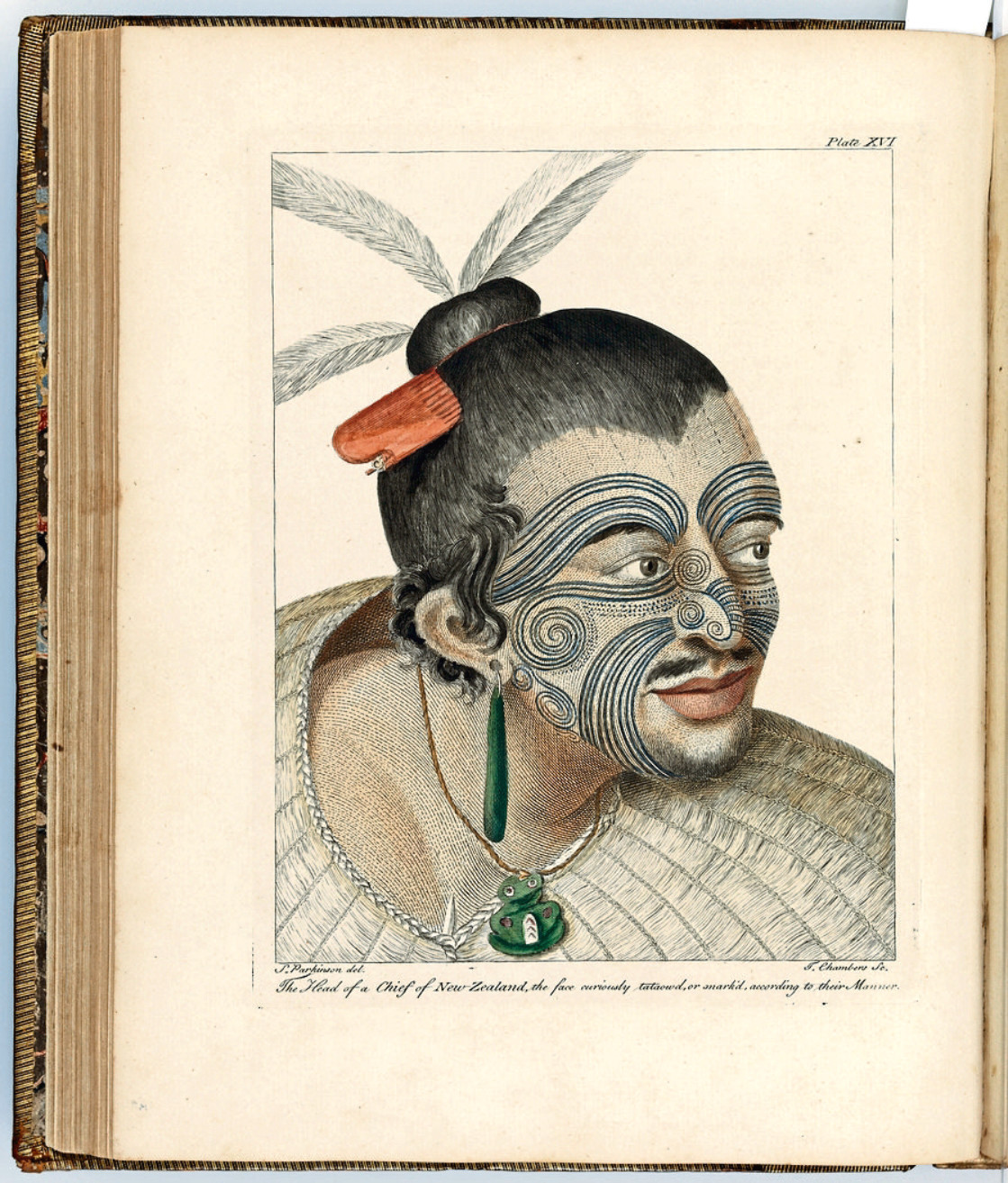

Arriving in New Zealand, Cook’s men encountered the native Maori. His incredible sketches of the native people are on display in the National Library of New Zealand, and show striking Maori warriors, complete with tribal facial tattoos and topknot combs.

In 1770, the Endeavour spent several weeks stranded in Queensland, in modern-day Australia, after hitting a reef. While onshore, Parkinson made two sketches of what would have been a bizarre creature – a kangaroo, the marsupial that is indigenous to Australia.

“The flesh of it tasted like a hare’s, but has a more agreeable flavour,” Parkinson reported, after the crew killed and ate the kangaroo they had spotted.

Parkinson struggled to keep up with the sheer amount of specimens the expedition gathered in the New World, which was teeming with previously uncharted life.

One of the natural harbours they encountered was so rich with plant life that Cook named it Botany Bay. Until that point the journey had been relatively safe with only a few deaths, which was unusual for the time.

However the return trip – which went via India – was where things began to go wrong for Cook and his men. Many of the crew, exhausted from the three-year journey, began to fall ill with dysentery, malaria and tuberculosis.

On January 26, 1771 Cook noted Sydney Parkinson died after contracting dysentery, and buried him at sea.

He may never have returned to the land of his birth, but Parkinson left 280 finished paintings and over 900 sketches and drawings.

“Parkinson’s ceaseless activity and massive output was greatly appreciated at the time, especially considering the rough seas and cramped conditions on board,” said Alwyn.

“There was great sadness at his early death on the return leg of the voyage.

“His work has become even more appreciated as time has passed with the full realisation of its extent. Especially as it was made under the difficult conditions of an 18th-Century voyage to an unknown part of the world.”

Although not as renowned as Captain James Cook, Parkinson does live on in the world of the plants which he loved to paint. The tree Ficus parkinsonii – which grows across Australia – was named after him.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe