For almost 20 years, Jim Ashworth-Beaumont helped build prosthetics for patients who had lost limbs and aided their rehabilitation.

Next week, he will return to work with a different perspective – after losing an arm in a cycling accident.

Six months ago, Jim, a prosthetist and orthotist, was on his way to work at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in London when he was knocked down by an articulated lorry. The 40-ton truck rolled over the 54-year-old, severing his right arm, and caused so much damage that Jim almost died.

“I was still conscious up until the ambulance arrived and 99% sure I was going to die,” he recalled. “Those were the odds at that moment. I remember the sirens. I remember hearing people talking in the background. It was terrifying.”

Jim, who comes from Edinburgh, was airlifted to hospital where he spent five weeks in a coma. As well as losing his arm above the elbow, he sustained nerve damage in his leg, spinal fractures, broken bones in his face and arms, and a fracture in every single rib in his body. The main artery to his liver was so damaged that doctors had to cut away 80% of the organ to save his life.

“They tidied up what was left of my arm and then I had an awful lot of surgery,” Jim recalled. “A lot of skin was grafted on to my chest and my abdomen where it had been torn away. Thankfully I was asleep throughout. It was so strange. I was dreaming all the time. I thought I was in the afterlife. The weirdest thing was seeing the faces of my wife and kids. I couldn’t work out whether I was dead and they were as well, or whether I was still alive.”

Jim’s family thought he had been through the worst, but worse was yet to come: “My kidneys packed in, I got sepsis and, about a week after the accident, I went into multiple organ failure.”

At one point, Jim’s family were so sure he might not survive that his 25-year-old son Sam stepped in to offer one of his own kidneys to his dad. “When I realised the sacrifice he was prepared to make, I realised just how close to not making it I was,” said Jim. “It makes me quite emotional.”

Thankfully, dialysis helped stabilise his condition and a transplant wasn’t needed. When the dad of two eventually came to, more than a month after the accident in July, he was completely incapacitated.

“I couldn’t speak and didn’t even have the physical strength to hold a pen,” he said. “In fact, the first time I got a word out was at the end of August when my mum came from Edinburgh to see me in hospital. It was her 80th birthday,” he said.

“I think that’s when the fight set in and I told myself I was going to get better. That was the turning point.”

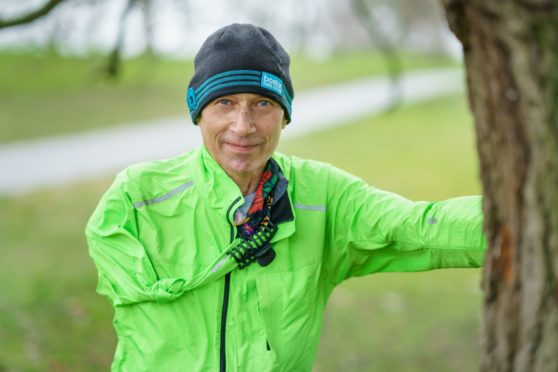

The former Royal Marine left hospital in November and since then has been putting himself through his paces with intense physio and training in the hope of speeding up his recovery.

The competitive runner, cyclist and fitness coach, who had been training for a triathlon at the time of the accident, has recovered to the extent that he is now able to complete 10k runs.

“Before the accident, I was the fittest I could ever be, but I’ve basically had to learn how to do everything again,” said Jim. “Stamina is what I know. And I think that is what has got me through.

“Physically I am different, but mentally there is something I savour about having a challenge. And, with every day feeling like I have an Everest to climb, you can’t say I don’t have a challenge.

“I might not be signing up for triathlons any more, but the challenges are right in front of me. I have had to adapt and learn new things such as left-handed writing and drawing, tying shoelaces and even how to juggle a mobile phone.

“Training within new limitations, such as my breathing, is all new, too. But there is so much I can do. The doctors initially told me I would need to change my mental attitude because it takes time, but that’s not in my nature. I feel most alive when I am pushing myself and am now exercising twice a day, six days a week.”

Jim said his selfless wife Keri had been his rock through everything. “She has helped me every step of the way. Keri has had to live with my frustration at not being able to do the things I did before. She has rearranged our home – and her life – to fit around me. I don’t know where I would be without her.

“On the day of the accident, she was cooking dinner waiting for me to come home. I wasn’t carrying any ID so she hadn’t been notified I was in hospital. When she eventually heard the news and got there, she thought I was going to die.”

Jim, who is due to return to work on February 8, albeit from home, hopes to be fitted with a prosthetic arm and hand which will allow him to get back on to the wards helping patients again, rather than being confined to a research role behind the scenes.

“I love my job. And now I can empathise with my patients even more. I create and fit prosthetics for children who have lost limbs through illness like cancer, adults who have lost arms and legs in traffic accidents, I make spinal braces for people with spinal deformities, and fit splints.

“These things can be gradual or come from sudden, life-changing events, but they impact an ability to do something.

“My role is all about taking a problem and solving it for someone so they can have a better quality of life. But this accident has opened my eyes to so much.

“Even though I’ve worked in the rehabilitation field for almost two decades, I have been surprised by the power of the simple things – extra locks on doors, zips on clothing, toilet roll holders on the right – to show me that functional barriers are still impeding those with differences in ability. I don’t feel as welcome in this society as I used to. An important future goal for me is to incorporate this new level of awareness into my service to patients.”

Jim hopes to have a specialist prosthetic arm fitted using a technique called osseointegration, in which the device is implanted into the bone.

But with the prosthetic and surgery not available on the NHS, treatment will be funded through money collected by Jim’s sisters, Lisa and Nicky, who set up an online appeal while he was still in a coma.

So far, family, friends, colleagues and well-wishers have pledged more than £100,000, about half of the money needed for the new arm and hand, surgery, and long-term maintenance. Jim is hopeful the operation can go ahead this year. “I’m overwhelmed,” he said. “It’s heart-warming to think that so many people have gone above and beyond to help.”

Jim hopes for a hybrid arm with a multi-grip powered hand and rotating wrist, and with a body-powered elbow to get maximum dexterity with low weight. He also hopes to have an activity-specific prosthetic made to balance his body for exercise.

“I make artificial limbs using a high degree of manual dexterity, so losing a hand is a bit of an issue!” said Jim. “The new hand is the most life-like you can get. The NHS prosthetics are great, but they are basic. The hi-tech models are expensive and most need to be funded privately. The hope is that by obtaining a prosthetic with a bit more technology behind it, I’ll be able to carry on doing what I love.”

He added: “What has happened to me has made me realise that you just need to make the best of what you’ve got. The downsides have by far been outweighed by the good.

“And it has been a stark lesson in what’s important in life, and whatever it throws at us, we just have to roll with it and hope for the best.”

Donate at tinyurl.com/jimschallenge

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied © Mike Stone

© Mike Stone © Mike Stone

© Mike Stone