ITV’s big Christmas Day drama Victoria is a festive feast with Prince Albert bringing German traditions, like indoor trees, to the Queen and the Palace.

Millions will settle down to watch Jenna Coleman and Tom Hughes, but the true Yuletide tale is a lot more complex, according to Judith Flanders’ new book Christmas: A Biography. As we get ready to open the presents, Bill Gibb offers us the ho-ho-ho-down on the most magical time of the year.

The earliest evidence of a celebration of Christ’s birth is when Julius I, Bishop of Rome (337–352), decreed Christ’s nativity was to be observed on December 25. From the start, Christmas seemed determined to break away from religion – around 389, the Archbishop of Constantinople warned against the dancing and “feasting to excess”.

By the reign of King John, courtly Christmas feasts had become elaborate. In 1213 the king’s household and guests consumed 27 hogsheads of wine, 400 head of pork, 3000 fowl, 15,000 herring, 10,000 eels, 100 pounds of almonds, and 66 pounds of pepper.

As early as 1419, a Freiburg city guild erected a tree decorated with apples, wafers, tinsel and gingerbread. The first decorated indoor tree we know of was in 1605, in Strasbourg. Adorned with paper roses, apples, wafers and sugar ornaments, it known as Weihnachtsbaum, or Christmas tree.

Soon, people were encouraged to Deck The Halls With Boughs Of Holly, or at least they were in Wales, where the carol originated in the 16th Century.

In Scotland in 1561, the newly reformed Kirk banned the holidays entirely. By the 1570s, court records in the Lowlands included a number of people for “marking superstitious days and specially Yull-day”.

James VI of Scotland’s love of holiday celebrations had been a problem for the Kirk, ensuring Christmas bans were impossible during his reign. After his death in 1625 the monarchy lost control in Scotland, and in 1638 the General Assembly banned Christmas outright.

To celebrate Christmas, said one newspaper, was to celebrate “Rioting and Drunkenness”. In Aberdeen at Christmas 1784, “A riotous assemblage . . . stimulated by drink and madness” attacked a Catholic church.

The first holiday market in Germany had been held in Berlin from the mid-15th Century. Berlin later had a famous market that by 1796 had 250 booths selling everything from textiles to toys, gold and silver trinkets, wigs, carved wooden objects, clothes and holiday cakes.

In 1848, the Illustrated London News published an engraving of Victoria and Albert with a table-top tree. The image cemented the Christmas tree in the popular consciousness, so much so that by 1861, the year of Albert’s death, it was firmly believed the German prince had brought the custom to England with him when he married.

The wrapped present arrived in the 19th Century. Gas and soot from coal fires made endless daily cleaning necessary, so covering was desirable. Happily, coloured printed paper became less expensive in the 1830s.

In 1882 the Edison Illuminating Company built the world’s first electrical power station. Four months later a Christmas tree in the home of one of Edison’s employees, blazed out with 80 red, white and blue bulbs.

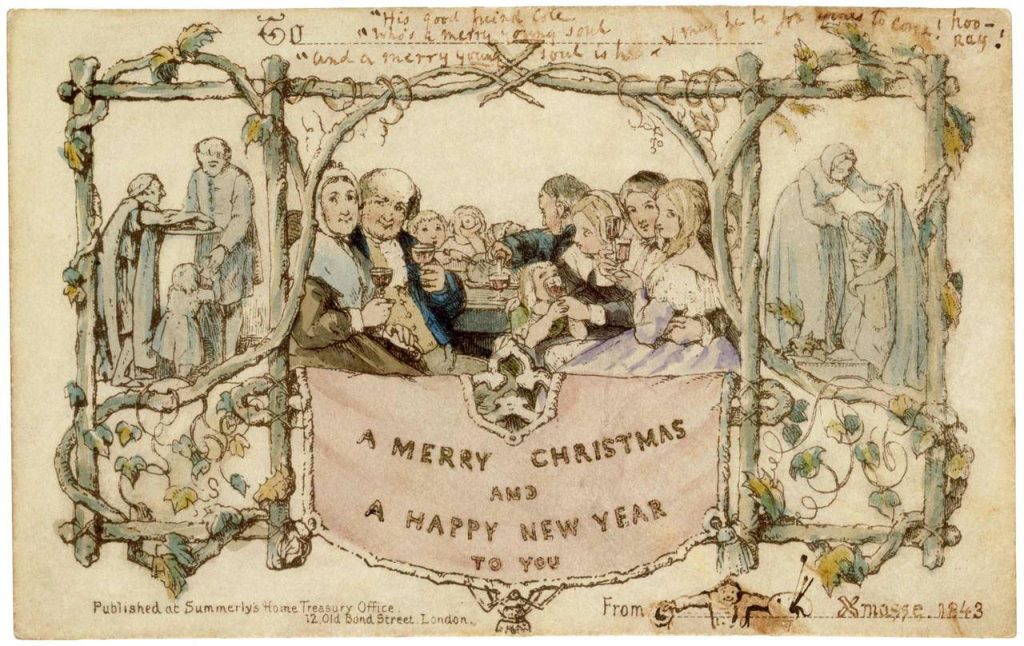

The first modern Christmas card was produced in Britain in 1843, two years after the creation of the penny post. The card’s centre illustration showed three generations of a family around a holiday table. Each card was hand-coloured, and sold for a very expensive 1 shilling.

What is striking for those who continue to believe Christmas was primarily a religious holiday is the lack of religious content across all cards in English-speaking markets from their earliest days. One historian has catalogued the subjects in a collection of more than 100,000 cards printed before 1890. The majority showed holly, mistletoe, Christmas pudding or Father Christmas.

To distinguish his sweets, Tom Smith a confectioner in London, wrapped them in paper treated with saltpetre, which made a bang as they were opened. He called them “fire-cracker sweets”. Gradually, the sweet was replaced by a modest gift, the printed wrapper became a motto or joke and the Christmas cracker was born. Tom Smith & Co. became a dedicated cracker-manufacturer, and by the 1890s was producing 13 million crackers a year.

The First World War Christmas Truce of 1914 was not a single incident, in a single place. On Christmas Eve, members of the Royal Flying Corps dropped a Christmas pudding over the German lines at Lille, reciprocated with a bottle of rum from the Germans. A German regiment sang carols and folksongs along a candle-lit trench, and as each candle was lit, the British cheered. They replied with songs such as The Boys Of Bonnie Scotland, and Where The Heather And The Bluebells Grow’. Gradually, men emerged from their positions to speak to those who, a day before, they had been doing their best to kill.

Irving Berlin wrote White Christmas as a song about a man in sunny California. Soon, however, the opening was dropped, and it became a song about the lost Christmases of the singer’s youth and was included in the wartime film Holiday Inn.

It’s A Wonderful Life was released in 1946, and barely made a ripple. The promotional material focused on the small town location, not the time of year, and it wasn’t presented as a holiday film. It became a seasonal classic after the film’s copyright expired in 1974 and it could be broadcast for free.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe