This week, every state secondary school in Scotland will receive a class set of a new book about the country’s involvement with slavery.

Freedom Bound is a collaboration between the University of Glasgow and BHP Comics, further imagined by artist and author, Warren Pleece who will also launch the book at Edinburgh International Book Festival today.

A graphic novel set in Scotland in the 18th century, Freedom Bound follows the stories of three young enslaved people. Each slave was brought to Scotland from the Caribbean and North American slave plantations they had originally been sent to from Africa, and then were subsequently taken to Scotland to wait on their wealthy Scottish masters.

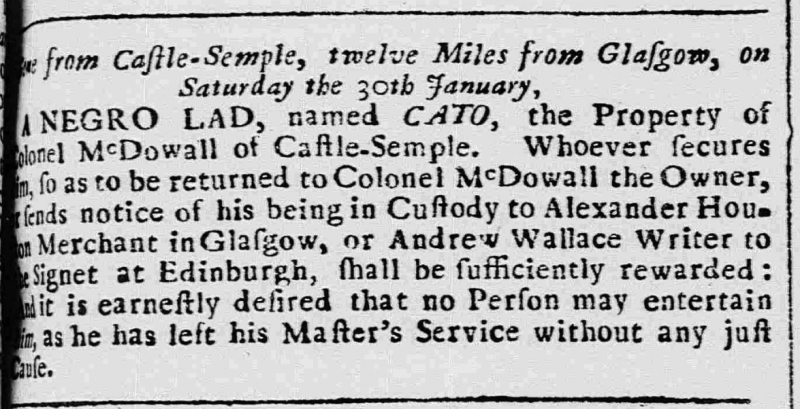

The book is a humanistic reflection of real stories of enslaved people in Scotland, based on the impersonal Scottish newspaper advertisements of masters searching for their runaway slaves.

Included are stories about a woman who is known only as Ann, who was made to wear a metal collar engraved with her master’s name, another is of Jamie Montgomery who escaped but was turned in for a reward and finally Joseph Knight, who achieved his freedom after a bitter legal battle.

Background

Up until recently, the information about slaves living within Scotland was of little discussed importance within the context of the Scottish past, with the slave conscience far removed to America and the British colonies in the West Indies.

However, thanks to the work of Simon Newman and Nelson Mundell of Glasgow University in their Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth Century Britain project, new information has been brought to light about the part Scotland had to play within the rubric of the period: many slaves were also in servitude here.

67 notices advertising for the recapture and return of enslaved people who had escaped placed in Scottish newspapers have been found between 1700 and 1780 giving an idea of how slaves were living in Scotland at the time.

From the Edinburgh Evening Courant to the Caledonian Mercury, adverts quite clearly describe the slaves as “property,” and offer up to six guineas reward (the equivalent of around £735 today) for the return of their slaves.

Slave Life in Scotland

Although on the surface, it may be assumed that life for slaves serving in Scottish mansions was slightly better than those doing the back breaking plantation work in the colonies, but according to research by Simon Newman, slavery in Scotland was just as cruel:

“Most of the enslaved brought to Britain were young, and generally male, and they were brought to be personal attendants and domestic servants (a few others were craftsmen, and some were sailors belonging to ship captains and officers).

“But we should not assume that this made slavery in Britain ‘better’. These were young people, sometimes not even teenagers, stripped away (sometimes from Africa) from families and communities and taken to alien environments.

“The threat always hung over them that masters might take or send them back to the colonies, to work or be sold, and to re-enter the hell of plantation slavery.

“So there was little comfort or security for many enslaved people in Scotland, even though on the face of it they lived in much better conditions than plantation slaves in the colonies.”

Collars and branding were applied to slaves in many cases, both to ensure slaves would be easily identifiable, and to exhibit the wealth of their owners. Indeed, it was highly fashionable to have a young male black servant or slave at the time.

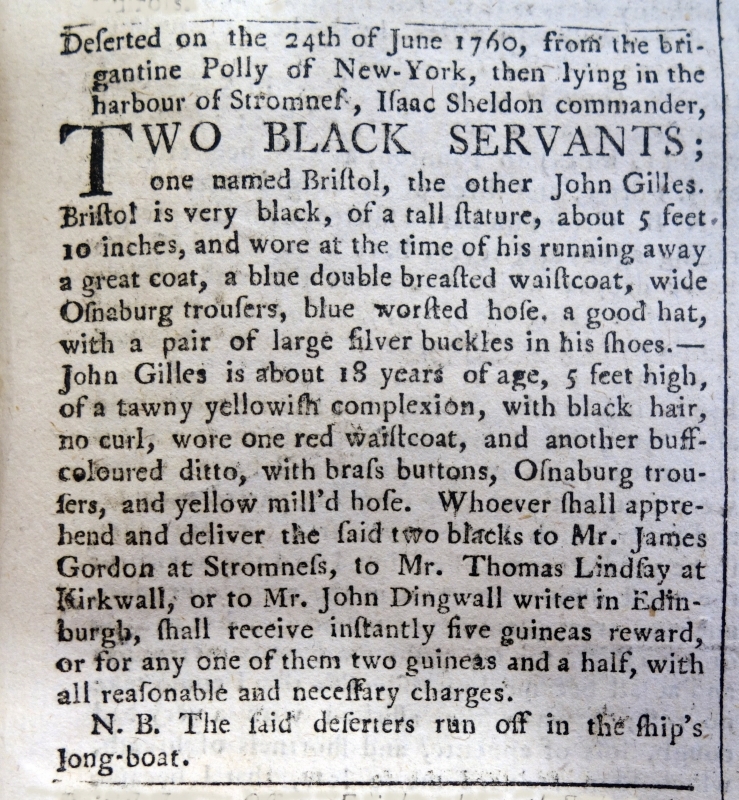

Slaves were escaping in the Scottish Islands

While recent accounts of Scottish links to the slave trade highlight Glasgow and the west of Scotland as the main reapers of the slavery benefits, slaves were in fact found across the country.

An account of two male slaves escaping in Orkney is advertised in a newspaper article in 1760, stating: “Whoever shall apprehend and deliver the said two blacks to Mr. James Gordon at Stromness, to Mr. Thomas Lindsay at Kirkwall, or to Mr. John Dingwall writer in Edinburgh, shall receive instantly five guineas reward, or for any one of them two guineas and a half, with all reasonable and necessary charges.”

Records of an escaped slave in Rossshire in the Highlands is also advertised in 1771.

“They were held everywhere,” says Newman. “The wealthy people who brought slaves back tended to have both urban town houses and big country estates, Ayrshire, Perthshire and Ross-shire were particularly popular.

“This, of course, could increase the isolation experienced by enslaved people.”

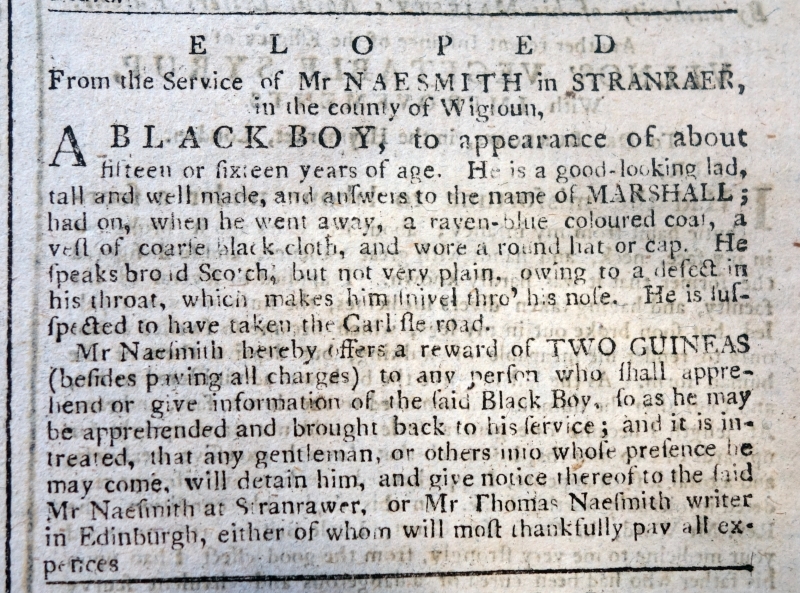

Scottish accents

Many slaves would have lived their entire lives in Scotland, surrounded by alien concepts, languages and accents. That slaves would have picked up their master’s accents and colloquialisms was therefore inevitable as made reference to in an advert for an escaped slave from Stranraer: “He speaks broad Scotch, but not very plain, owing to a defect in his throat, which makes him snivel thro’ his nose.”

While picking up this distinct aspect of Scottish identity, slaves were still treated as “other” in Scotland, with hefty rewards meaning many white Scots would happily turn in an escapee.

Likewise, many adverts of slaves “for sale,” have been uncovered in newspapers of the era, put in the same section as livestock sales and shockingly with much of the same descriptive wording. It appears the British public had no issue with the sale of humans at this point in history, as there is no record of any complaints being made against the ads.

Post slavery

Slavery effectively ended in Scotland in 1778 after the success of Joseph Knight winning his freedom from his master, James Wedderburn after a protracted legal battle in the Scottish courts.

Before this however, it is likely that free escaped slaves would have tried to integrate into society as best as possible, changing their names and travelling anywhere they thought may be safe.

“A successful escapee is one who disappears from the records,” says Newman. “Some appear to have headed to the Highlands, others to major towns and cities (presumably in search of work and small communities of black people).”

What Newman and Mundell have observed through their findings however is that no escaped slaves made any attempt to return to the colonies they had been brought to Scotland from:

“Many sought to make lives for themselves here, joining churches, marrying etc., within white Scottish and British society.”

The likelihood is therefore that while the many streets and houses running through Scottish cities were built on the back of distant slaves creating profits in far away colonies, many unbeknownst Scots walking those streets today will have that same slave ancestry running through their DNA.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe