He has birds named after him, Oscar winner Daniel Day-Lewis played him in a blockbuster film and he is lauded as the godfather of American birdwatchers.

But, in his homeland, Alexander Wilson remains largely unknown.

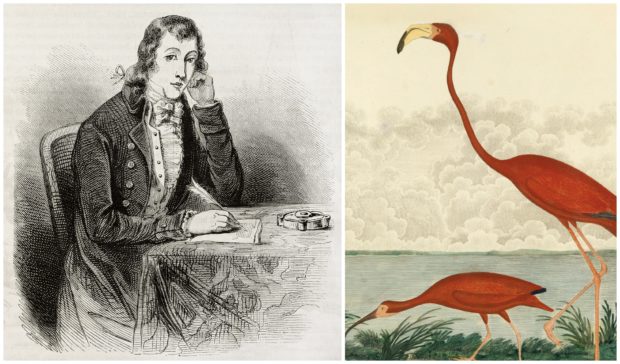

Now the achievements of the Paisley-born ornithologist are highlighted in a book saluting his legacy and influence.Burds In Scots is illustrated with Wilson’s beautiful pen-and-ink paintings from his groundbreaking, nine-volume American Ornithology.

He was a daring and remarkable man, a radical working-class weaver and poet who left Scotland after being imprisoned in 1793 for his seditious poems – which he was forced to burn publicly – about the exploitation of millworkers in his home town in Renfrewshire.

In his new life in America, he became a teacher and took up natural history, travelling the length and breadth of the vast continent on foot, recording birds and drawing them from life in their natural habitat – the first person in that country to accurately and scientifically describe 268 native species.

Today, he is renowned and revered across the USA, where there is an ornithological society and journal named after him, and his name has been given to the many birds he discovered, such as Wilson’s Warbler and Wilson’s Storm Petrel.

Paul Walton, head of species and habitats for RSPB Scotland, wrote the introduction to the book, which comes out next month.

He said: “I’ve always been a Wilson enthusiast and I’m delighted that this book will bring him to the attention of a Scottish audience. In America he is known as the father of ornithology.

“He was an adventurous, intrepid character who walked vast distances in the US, living comfortably in the wild. James Fenimore Cooper said he based his character Hawkeye in The Last of the Mohicans on ‘the Scotchman Wilson’.”

Daniel Day-Lewis played Hawkeye in the 1992 Hollywood film based on the classic American novel.

“Wilson was a major player in the Scottish tradition of natural sciences,” added Paul. “But he remains obscure in Scotland.

“There’s a statue outside Paisley Abbey of Wilson holding a dead bird, which he is studying, but many locals have no idea who he was.”

Paul hopes this new book will help us appreciate our native wildlife and bird population, which is under threat from climate change. “We are losing nature in Scotland because of global climate change and the ecological crisis, with many species under threat,” he said. “There has been a 38% decline in breeding seabirds over the past nine years and Scotland holds half of the breeding seabirds in the EU.

“There has been a 70% decline in the kittiwake population, and the corncrake has only just been saved from extinction. When Alexander Wilson was alive every single county in Scotland had corncrakes but now they can only be found in the Western Isles and Orkney.”

In Burds In Scots, Wilson’s illustrations are accompanied by their Scots names and poems in Scots by Hamish MacDonald, a former Scottish Scriever at the National Library.

“I stumbled on Alexander Wilson when I was researching the library’s publications in Scots,” said Hamish.

“I was looking through a rare manuscript when a piece of paper fell out of a book and it was a poem in Scots by Wilson. I started looking into him more and read his pamphlets and his nine volumes of American Ornithology.

“I became fascinated by his story and wanted to share it more widely – he’s not as well known as he should be in Scotland, not like John Muir by comparison, who went on similar adventures.

“His poems in Scots are vibrant and rich. He used to walk 60 miles from Paisley to Edinburgh to deliver them at the Pantheon Club, a debating society, in front of 500 people.

“Most interesting are the political poems that satirised the mill owners for being usurious and ripping off their workers. Poems such as The Hollander and The Shark don’t name the mill owners but they were thinly-veiled attacks on well-kent individuals.”

The Hollander is a satire describing the atrocious working conditions in the Paisley textile mills and a plea for unionisation. Reformers and workers admired these poems, but the mill owners were furious and one of them accused Wilson of blackmail, demanding £5 in exchange for suppressing publication, an accusation that he denied.

Wilson was imprisoned several times and in 1793 ordered to burn his poems in Paisley Square.

When the libel and blackmail charges were dropped, he moved to America, where he was enthusiastic about American democracy, writing a poem about Jefferson as part of his presidential campaign.

In America, he became friends with William Bartram, a botanist, and was drawn into the world of natural history, of observation, recording, drawing and painting. American birds were not properly classified or catalogued at the time and Wilson took it upon himself to put this right.

“He donned buckskins, took up his rifle, paints and notebooks, and set off, on foot, from Pennsylvania to Niagara, returning by an alternative route,” said Paul Walton.

“It was the first of many long field expeditions across the continent. Wilson is estimated to have walked at least 12,000 miles between 1804 and 1813, recording birds all the way, visiting every state on the US mainland and developing a comprehensive overview of the country’s bird fauna.”

Hamish was inspired by Wilson’s poetry and American Ornithology to write poems in Scots about the “burds”, along with their Scots names, such as the Houlet (owl), the Smaw Douker (little grebe), the Gowk (cuckoo), the Specht (woodpecker), the Pyot (magpie), and the Brongie (cormorant).

He poems are lively and playful: Birdsang O The West interprets birdsong with the street phrases “See-you-pal. See-you-pal. Giez a brekk. Giez a brekk. Giez a brekk. Squerr-go-then. Squerr-go. Ya-brammer-ya-brammer-ya-brammer”.

Their cousins, on the east coast, however, sing in Doric: “Fit-like-min? Fit-like-fit-like-fit-like? Tyaavin-awa-Tyaavin-awa. Foo’s it gan? Foo’s it gan? Yer seein it. Yer seein it.”’

“I knew some of the bird names in Scots but enjoyed discovering others from different dialects around the country,” said Hamish. “Some of the language in Scots is so apt, such as Smaw Douker for the little grebe.

“I absolutely enjoyed working on this book. I’m not an ornithological expert but I’m enthusiastic about birds and this gave me an opportunity to write about them in Scots, as well as tell the extraordinary story of Alexander Wilson.”

Wilson died in Philadelphia in 1813, aged 47, exhausted by his ambition to complete American Ornithology.

“In the end, he was perhaps the most perfect American Dream,” said Paul.

“Child of the Scottish Enlightenment, driven by persecution to America, where he was free to roam and to think, to earn through mind and muscle, talent and drive, to pursue his own unique happiness and build a profound legacy along the way.

“He died proudly, legally, emphatically an American. But he was born and raised, equally emphatically, a Scot.

“This book, with 54 of Wilson’s beautiful paintings of birds and the accompanying poems in Scots, is a lovely way to celebrate his life and work.”

Wilson’s Ornithology & Burds In Scots, with illustrations by Alexander Wilson, and poems by Hamish MacDonald, is available to order from scotlandstreetpress.com

Ailsa Paurit/The Puffin

The Ailsa Paurit gairds the Craig

in snaw-white downie tabart

a pirate coat upon his back

an cutlass in his scabbart.

Huffin an puffin amang the gress

it widdles then it scurries

wi colourt neb tae brod an jeb

the seamaw frae the burraes.

High on the sea-girt curlin stane

Wi cruin an gurly greetin

Feedin on the Tammie-yaw

Whan simmer tides are fleetin.

The Crossbill

The crossbill is a bonny burd

The crossbill is a bonny burd

An she sings wi a guid Scots tongue

Jip jip jip

A’ll gie ye gip

Gin ye meddle wi me nor ma young

The crossbill is a brawlike bird

An she dines on the cones an the nits

Her neb is unique

Wi a crossower cleek

An the heich pine croon’s whaur she flits

The crossbill’s a hamefarin bird

An she trills her dowie sang

By the hilltaps o Straloch

Or by wild foamin Falloch

Contentit tae bide saison lang

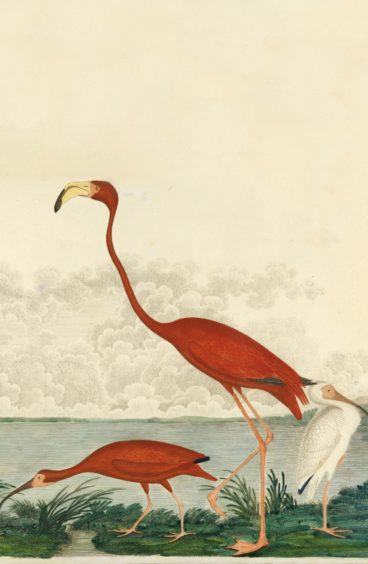

The Big Rid Flamingo

The Big Rid Flamingo has lang spirlie shanks

The Big Rid Flamingo has lang spirlie shanks

Circus stilt-walker o mudflats an banks

Skinnymalink neck, souple an lean

Bricht bonnie feathers wi cramasie sheen

Howks in the glaur wi its muckle strang neb

Tae find gustie morsels that dwall in the ebb

Like a sieve in its mou that is awmaist complete

It’ll filter aff shrimps an sic braw things tae eat

For grace an yet gangliness

And pure lang-necked dangliness

The Big Rid Flamingo is gey haurd tae beat

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Steve Brown / DCT Media

© Steve Brown / DCT Media