Greeted by an unseasonal deluge accompanied by brutal leaf-stripping gusts, I made my way to meet Myrtle Simpson at her home in the Cairngorms.

Having driven down a track close to Insh Marshes, going into Myrtle’s house is to enter a realm of ice caps, icebergs, pristine snow-clad summits with vertiginous knife-edge ridges, skis, sledges, kayaks and crevasses, eternal whiteness and danger.

Walls are covered with astonishing photographs – her four children with Inuit kids; the family camping on the tundra; Myrtle, with a baby on her back, crossing a vast openness of white; brown, weathered, ice-rimed faces smiling from fur-clad hoods.

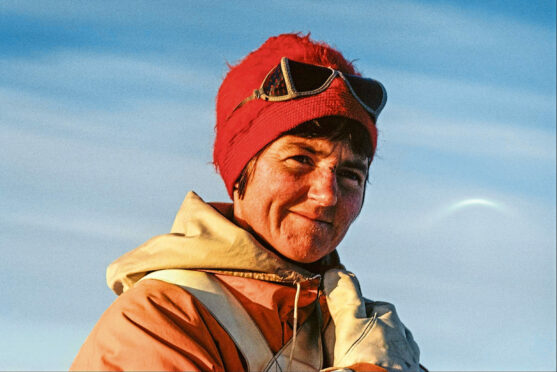

An effervescent, enthusiastic Myrtle greets me. In 2017, Myrtle was awarded the prestigious Polar Medal for services in the Arctic. She was only the 10th woman to achieve this accolade – one that her husband, Professor Hugh Simpson, had won earlier for his medical research in the Antarctic.

Theirs was a unique trailblazing partnership of more than 60 years. A catalogue of intrepid exploring and researching, often accompanied by their four children, and long periods spent living with indigenous people in some of the most hostile environments.

“I wasn’t educated much at the start, you know,” says Myrtle, which makes me giggle given her mind-blowing achievements, the fact that she has written 12 books, and countless articles on the high Arctic.

These helped fund their sojourns to the highest undiscovered mountains of Peru and the Himalayas, and many of New Zealand’s virgin peaks.

In 2018, National Geographic named Myrtle one of four women who defied expectations and explored the world. Yet, talking to her as she stirs homemade soup on the Aga, she is humble and modest – and always exceptionally entertaining, with sparkling humour.

“You don’t need to be gym-fit before you go on these expeditions – this is all about good, old-fashioned women’s stuff, honestly just a question of slogging on regardless,” she assures me.

Myrtle is now 91 but looks more like 70 and retains the joie de vivre of a child at Christmas, fascinated by everything and everyone around her, and still embarking on expeditions closer to home, often with her four children and 10 grandchildren.

“They are all outdoor enthusiasts and love adventures like me,” she says. “We could swim in the loch later,” as rain obliterates the view of her extensive wooded garden.

I wouldn’t dream of calling myself an explorer, but I was fortunate to live at a time when it was still possible to climb a virgin peak. I have climbed a few of them.

“It’s an extraordinary feeling to be somewhere totally undiscovered and to live off your wits surrounded by danger – that’s part of the fun.

“Sometimes I sit next to someone at dinner, and they tell me they are an explorer, that they have been to Greenland or the Poles, but they flew in and had a support team, or even went on a cruise ship – that’s not exploring.

“We did it differently in the 1950s. I used to get endless criticism about the children, that leaving them behind was a bad thing. But they came too. That was criticised also.

“Happiness to me is having your children around you, snuggled up in a tent – even in the worst weather – with a good book. And it was so good for them to experience all these amazing places.”

“I must show you the komse,” she continues. “Made from birch wood and reindeer skin, it’s strong, for safely transporting a baby. Hugh swapped it for a bottle of Drambuie when we were in Spitsbergen.”

Myrtle trained as a radiographer in Edinburgh before taking her first job in Fort William.

“I was mentored by the hospital’s only surgeon, Donald Duff, who was a revered climber. He was a pioneer of mountain rescue and invented the Duff stretcher.

“Sometimes, if it was a good day, Donald would shut the hospital and we’d take to the hills. I would be paid 10 bob to lead visitors up Tower Ridge on Ben Nevis or some of the other peaks. There was great opposition to girls taking part in climbing trips but, fortunately, because I was with Donald, I was accepted.”

An air of nostalgia surrounds us as we sift through boxes of photographs and albums brimming with features written by Myrtle and yellowing newspaper cuttings.

She tells me that when she and her climbing friend Billy Wallace decided to plan an expedition to climb some high peaks in the Andes, they needed a third person and asked another experienced climber, Hugh Simpson, to join them. “People took bets on which one I would marry by the end.”

In his fascinating obituary of his father, their youngest son Rory writes: “Perhaps due to the adverse effects of high altitude Hugh subsequently became engaged to Myrtle… Adventure was always part of the couple’s DNA.”

As I sit with the rain battering down the French windows into a garden that Myrtle still tends herself, I am overwhelmed by the achievements of this brilliant woman.

Myrtle had a similar effect on American film director Leigh Anne Sides, who recently made an outstanding short documentary film about her – A Life On Ice.

“I found her story inspiring and affecting but was surprised to learn it wasn’t more widely known. Her achievement of being the first woman to cross Greenland on foot was remarkable – especially in 1965, as a mother and in the face of harsh criticism,” Leigh Anne says.

“It was so hard to keep the film within the allotted time limit. I had to leave out huge parts of Myrtle’s story.

“When the film became such a hit at film festivals, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to record more of Myrtle’s life. I want to expand on the topics of gender equity in extreme sports like polar exploration.

“The Simpsons witnessed some of the earliest signs of what we’ve now come to recognise as climate change.

“The ice cap was beginning to melt even then, and that disrupted their plans. We are looking for funding and sponsorship to make a feature-length documentary film.”

Watching A Life On Ice moves me deeply. It’s the poignant and important story of a unique partnership of two of Scotland’s greatest pioneer explorers of our time, and also of their four children who shared in their memorable adventures – a story for great celebration.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe