By 2003, I had seen Joan Baez perform many times and I would see her many times more but, one night of a sweltering summer, in Princes Street Gardens, I counted myself lucky to see her play in the city where her mother was born.

That hot Edinburgh night – ironically, the concert, supporting a global campaign against landmines, had to break for the military tattoo in the castle above – Baez, of course, sang one of the great Scottish ballads with which she is forever associated. Mary Hamilton, often known as The Four Marys, was the song and she told the audience that she’d spoken to her mother, who’d asked that, if she had time, maybe she could find the little church in which her father, William, had preached.

Baez recounted how she and Chrissie Hynde, another performer that night, had set off down Princes Street and found “the little church”, which turned out to be rather big and beautiful: St John the Evangelist, at the junction of Princes Street and Lothian Road, a Scottish Episcopal church that is home to the Just Festival of Spirituality and Peace, and which is celebrated for its ecumenism and radical murals.

Fifteen years later, in March 2018, Baez was back in the city during her Farewell Thee Well tour. With her son, percussionist Gabriel Harris, and multi-instrumentalist Dirk Powell (who together comprised her “big band”) she revisited the church and sang from the pulpit – The President Sang Amazing Grace, Zoe Mulford’s song about President Obama’s tribute to the victims of the 2015 Charleston church shooting. Posting on Facebook, she wrote: “This is inside St John’s Church in Edinburgh. Dirk is playing the organ, and I am singing at the pulpit from which my granddaddy once preached.”

Her granddaddy was William Henry Bridge and her mother, Joan Chandos Bridge, was born in Edinburgh, on April 11, 1913, at 19 Manor Place. It is said she is descended from the English Dukes of Chandos, the Brydges family, who were great patrons of the arts – Handel wrote his Chandos Anthems for the first duke. A direct line is difficult to discern but what’s certain is that Chandos is the middle name that’s been passed down the family and it seems appropriate that her own daughter, Joan Chandos Baez, would grow up to be a musician.

The Bridge family left Edinburgh for Halifax, Nova Scotia when Joan was a toddler and William was widowed shortly thereafter. His daughters endured a peripatetic upbringing and two rather wicked stepmothers – William’s seemed a rackety old life but he clung to his core beliefs, in 1933 establishing a fellowship centre in Mount Kisco, New York State, “an educational project for the promotion of peace”.

His daughter met and married Albert Baez, a handsome young Mexican scientist who would co-invent the X-ray reflecting microscope. He, too, was the son of a minister, a convert from Catholicism who established the first Spanish-speaking Protestant church in Brooklyn, where his wife, also Mexican, was active in the community.

The couple bought a summer camp for Latino kids which Regalada Costello, now 91, remembers as both camper and counsellor. Father B and Mother B, as they were known, were apparently “parents to everyone”.

So the little girl they all called Joanie and whom the world would know as Joan Baez did not fall far from the tree, her commitment to peace and justice innate and unshakeable. It was Joanie’s mother, known as Big Joan, who had been educated by Quakers, who suggested the family attend the Buffalo Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends in the late 1940s when her husband was having a crisis of conscience – Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, where he was working on the development of an X-ray telescope, wanted to co-opt professor Baez for a military project. Though not yet a pacifist, he was uncomfortable with the use of science for military purposes.

Little Joanie and her sisters Pauline and Mimi hated the weekly silences yet the importance of those weekly meetings cannot be overstated and through them, and through the Quaker youth social action wing, Joanie would meet two people who would have a profound effect on her life – Ira Sandperl, a Gandhi scholar with whom she would establish the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, and a young preacher named Martin Luther King. She was just 17 when she first heard him speak and he gave “a shape and a name to my passionate but ill-articulated beliefs”.

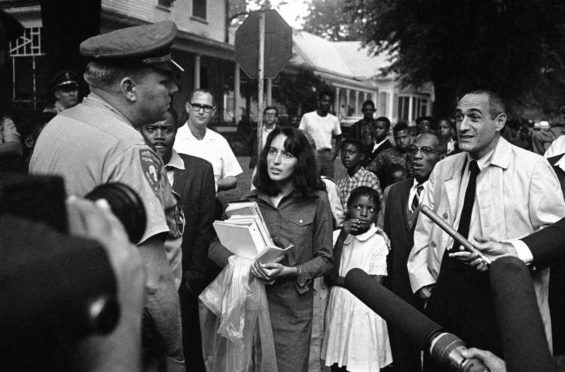

Five years later, on August 28, 1963, Baez stood beside Dr King at the March on Washington, when King dreamed his great dream. She was also with him on many pivotal occasions in the south during some of the bloodiest years of the civil rights struggle.

Her unshakeable belief in non-violent activism led her to take many risks: in Vietnam during Nixon’s Christmas bombardment; in Latin America during the most violent years of dictatorship, when she was directly threatened; in Israel and the Occupied Territories, asking only that “the dialogue of death should cease”; in Czechoslovakia, where she sneaked dissident Vaclav Havel, into a concert; in Poland, in the hinterland between martial law and democracy; and in Sarajevo during the siege where, flak-jacketed, she toured the streets, danced with firefighters, visited hospitals, and gave concerts across the city.

Music and social action have always been the warp and weft of her life, and her remarkable 60-year career, which began with an unannounced appearance at the 1959 Newport, Rhode Island, Folk Festival and ended at Madrid’s opera house in July last year, was as remarkable as it was influential.

Whether singing Scottish ballads – among them Henry Martin, Silkie and Geordie – to her own carefully crafted guitar, or Bachianas Brasileiras No 5, an aria for eight cellos and sopranos in which Heitor Villa-Lobos fused Brazilian folk song with Bach, her voice was peerless, phrasing, diction and pitch always perfect. She was a natural.

And let’s not forget her championing of young singer-songwriters, including Phil Ochs, Tim Hardin and, of course, Bob Dylan, whose songs she recorded when he was still a ragamuffin minstrel scuffling for dimes in Greenwich Village coffee houses. She had two albums in the charts and her portrait on the cover of Time Magazine when she introduced him to her audiences at Forest Hills and the Hollywood Bowl. Not everyone appreciated his voice but Baez persisted.

Big Joan, who died just a few days after her centennial, appreciated Dylan’s songs but never understood her daughter’s infatuation with him. Their brief but intense relationship is laid bare in her 1975 song Diamonds & Rust, a perfect miniature which I was privileged to hear her sing at the live sessions for her 1995 album Ring Them Bells. The locales mentioned – Washington Square and “that crummy hotel”, now an elegant, family-run boutique hotel that is my New York home from home – were but a stone’s throw away. It was unbearably poignant.

Approaching 80, Joan Baez is now embarked on a new chapter of life, portraiture – Dr Fauci, Ruth Bader Ginsberg and of course King, Havel and Dylan are among her many subjects, and her paintings have raised $100,000 for Covid funds. From her cosy California kitchen, she sung to a world in lockdown, songs in Italian, French, German, Spanish and of course English, messages of hope and solace in the darkest of times.

Joan Baez has cast both a deep spell and a long shadow, a woman who stands at the crossroads of music and social activism who consistently put doing what was right ahead of doing what was popular. Hers is a life that demonstrates the transformative power of music.

The songs

Joan Baez has always felt “an extra connection to Scotland” and proclaimed her pride in her “strong Scots blood,” writes Elizabeth Thomson.

Asked about any other inheritance, she replied: “I know it’s in some of the music, the early ballads. That would go back to my mother’s side.”

Three great Scottish ballads, among the 305 English and Scottish Popular Ballads identified and catalogued by Francis James Child, Harvard’s first professor of English, feature on her earliest recordings and demonstrate the natural beauty of her voice, its light and shade, and her skill as a guitarist.

Mary Hamilton

From her 1960 debut, mixes history and folklore. Recorded in a single take, without a run-through.

Henry Martin

From the same album, a story of piracy and revenge on the high seas. Baez’s voice is dramatic and exciting, her guitar playing skillful.

Silkie

From Joan Baez Vol. 2, a tale of those mythical creatures associated with the Scottish islands. Like many folk songs, it is modal – not in a major or minor key.

Joan Baez: The Last Leaf, by Elizabeth Thomson is published by Palazzo

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Ken McKay/ITV/Shutterstock

© Ken McKay/ITV/Shutterstock © Dezo Hoffman/Shutterstock

© Dezo Hoffman/Shutterstock