Not every father would lower their 13-year-old son into freezing Loch Striven in a leaking old diving suit while experimenting on decompression.

But then not every father was John Scott Haldane and, in fairness, not every son was JBS Haldane.

The father was already a pioneering scientist – his son would become one – and both shared a willingness, possibly an enthusiasm, for using themselves as guinea pigs.

The boy survived Loch Striven, just, as he was pulled to the surface and the safety of HMS Spanker as his suit filled with water.

He also survived being sent down a mine to establish how many lines of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar he could recite while breathing methane. He managed five before fainting.

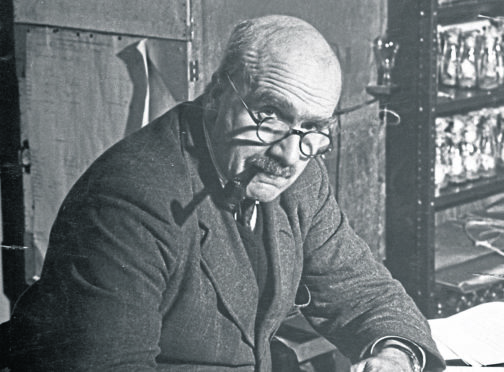

JBS Haldane not only survived but thrived to become one of the most celebrated biologists of the 20th Century. But behind the image of an eccentric scientist bent on self-experimentation, his communist beliefs provoked MI5 to investigate the possibility he was a Soviet spy.

It was Haldane’s roots in Scotland which inspired both his scientific discoveries – as well as his fascination with communism, according to a new biography about the man, by author Samanth Subramanian.

A Dominant Character explores the life of Haldane and reveals his inspiration came from serving with soldiers of The Black Watch in the First World War. And his enthusiasm for self-experimentation began at the bottom of Loch Striven in 1906, as that gangly 13-year-old.

“Haldane was a teenager when his father sent him to the bottom of Loch Striven, off the coast of Rothesay, in a diving suit that was too big for him,” said Samanth.

“By the time he was pulled back to the surface, his suit was flooded and Haldane was almost unconscious.”

Haldane’s father John was a Scottish physician who also had a habit of experimenting on himself – and subsequently his young son.

“The loch was so emblematic of his childhood,” said Samanth. “His father had no compunctions in sending him down to the bottom of the loch. Their beliefs were that everything that could be done in the pursuit of scientific truth, must be done. The family motto for Haldane is ‘Suffer’, after all.”

The diving suit experiment aimed to help the British admiralty work out the best way of bringing up divers to the surface safely and quickly without experiencing crippling decompression sickness, the notorious “bends.”

The younger Haldane went on to carry out similar work by measuring the chemical composition of his own blood while working as a scientist at Oxford University. The way to do this was by ingesting hydrochloric acid – which he would have given to a rabbit but, Haldane said, there was no way to ask how the animal was feeling.

Instead he drank the acid, almost melting his teeth in the process. He also sealed himself in a room with only 7% oxygen – air has 21% oxygen – and gave himself a violent headache. One experiment in a chamber triggered seizures so violent he broke vertebrae in his spine.

Although his work prompted gasps of disbelief among his colleagues, the image of a mad scientist was one which Haldane embraced. And he proved popular among the men of the Black Watch, with whom he served during the First World War, for his bravery and ferocity in battle.

“Haldane went to Eton where he was bullied, but when he went to war I think that’s the first time in his life that he didn’t feel out of place,” said Samanth. “He came away from the First World War loving the experience of being in battle.

“It was the Army but for him he really was in a place which fit his ideas of what a democratic public sphere should be, where the ranks of class were suddenly not quite as important any more.”

Haldane became a socialist during the First World War, and joined the Communist Party in 1937, writing articles for The Daily Worker. He stubbornly supported communism before eventually leaving the party in 1950, but still admired dictator Joseph Stalin. MI5 agents regularly attended his speeches and opened his letters, while British authors have accused Haldane of being a Soviet spy.

The attention didn’t stop Haldane’s work, however. He excelled in a number of fields, making groundbreaking discoveries in enzyme kinetics, animal allometry and even the origins of life. It was Haldane who supposed in 1929 that life came from a “primordial soup” of chemicals.

His most important work, along with two more scientists, was showing how two supposedly conflicting theories of genetics – Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and Gregor Mendel’s theory of inheritance – didn’t conflict.

Haldane popularised the idea of cloning, and was the first to suggest IVF treatment. As well as praise for his remarkable achievements, he remained dogged with controversy over his support for Soviet Russia.

When he moved to India – where he died in 1964 – he remained a committed socialist.

“The two big themes that inform Haldane’s life are science and politics,” said Samanth. “The ways in which they intersected in his life are quite relevant to our times because we’ve seen all these assaults on truth by people in politics and we’ve realised that these two things are not as far apart as we thought.”

A Dominant Character: The Radical Science And Restless Politics Of JBS Haldane by Samanth Subramanian is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock / Joe Dunckley

© Shutterstock / Joe Dunckley