Saturday will mark 65 years since the death of one of history’s truly great thinkers.

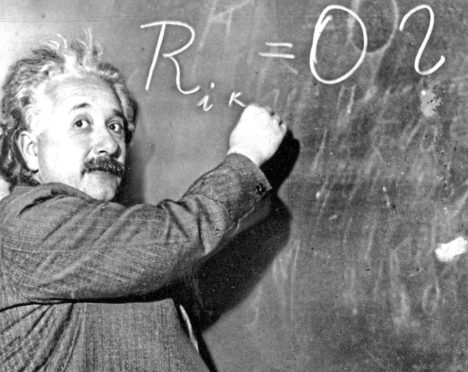

Albert Einstein passed away at the age of 76 on April 18 1955, having changed the world forever with his incredible intelligence.

For a man who had been kicked out of school for misbehaviour, and who only started his great work when he had some spare time from his day job, he would confound everyone’s expectations.

He was born in Ulm, Germany, on March 14 1879, the family soon moving to Munich where his education would begin.

In years to come, he was fortunate to find himself in the safety of the United States when Hitler came to power – with his Jewish background, Einstein stayed safe by not returning to Berlin.

Born a German, and a US citizen by his death, Einstein had a string of other identities during his life.

At one stage, he was stateless, then he became a Swiss citizen, next a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, before being a subject of the Kingdom of Prussia and again a German citizen, this time of the Free State of Prussia.

Whatever he regarded himself as, the world regards him as the man who laid all the groundwork for everything from nuclear weapons to cosmic science.

Einstein could think more deeply than everyone else about the minutest things and the biggest, and it turned out that he literally had a brain unlike most people’s.

After he died, they removed his brain and preserved it for Canadian boffins to study.

They found that the part of his brain used for mathematical ideas and thinking about space and movement was 15% wider than the average.

It was also missing a groove that runs through that part of most brains, leading to the fascinating theory that the neurons were able to communicate differently from everyone else.

All of which meant it was no shock when in 1999 he was named Person Of The Century.

Today, some believe Einstein may have been autistic, but what’s certain is that he was extremely brainy, although he could also be very quirky and not at all what you might expect from a genius.

When we think of a certain photo of him, it’s clear that he was capable of being as daft as the rest of us, and Einstein often didn’t take himself or life too seriously.

The famous photo was taken on his 72nd birthday, when he had grown bored with so many snappers asking him to smile. For Arthur Sasse, he stuck his tongue out, and the photo has featured in everything from T-shirts to cartoons ever since.

He loved it, even requesting several copies for himself, and one he signed raked in $75,000 at auction.

Einstein also admired women, of course, and wrote passionate, heartfelt letters to old flames, even when he was now involved with someone else.

Marilyn Monroe, it is said, fantasised about him, and an actress who knew them both reckoned they even had an affair. The blonde bombshell and the brain of the century, what an odd couple!

Einstein loved all kinds of things, not just women, and he often said his dream job would be as a plumber. At the same time, he had a lifelong love of music, except when they got him a proper teacher as a kid.

He rebelled and said he hated having to play to learn. But when he just turned to instruments when he felt like it, he quickly mastered them, too.

Those who heard the young Einstein play Beethoven said he showed a remarkable talent and deep love of the music, and near the end of his life he was still playing well enough to amaze professional classical musicians who heard him.

“If I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician,” he once said. “I often think in music, I live my daydreams in music and see my life in terms of music. I get most joy in life out of music.”

But by 12 he probably knew where his future would really lie. By that age, he was teaching himself algebra and geometry.

A teacher revealed that he devoured textbooks and soon moved on to loftier matters that even adults couldn’t grasp.

“He thereupon devoted himself to higher mathematics, and the flight of his mathematical genius was so high I could not follow,” one admitted.

Philosophy, too, grabbed his imagination. Kant’s Critique Of Pure Reason was an unlikely favourite for a kid.

His tutor reported: “At the time he was still a child, only 13, yet Kant’s works, incomprehensible to ordinary mortals, seemed to be clear to him.”

He entered the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich in 1896, aged 17, to train as a physics and maths teacher, but would struggle to find work because he was still officially German.

Needing money, he took a job as an assistant at Switzerland’s Patent Office. Crucially, it gave him plenty spare time to begin working on the mathematical theories that would alter the world forever.

By 1905, he published his Special Theory Of Relativity, describing the motion of particles moving close to the speed of light.

Germany, astonished at what he was achieving, was desperate to lure him home, and he had top positions in Berlin before also accepting a part-time role at America’s famed Princeton University.

That was where the Nazis came in, and where Einstein put down permanent roots in the USA.

The son of a salesman, who fancied plumbing and piano-tinkling, would come up with “the world’s most famous equation”: E = mc squared, known as his mass-energy equivalence formula.

It was the theory that anything with a mass also had to have an equivalent amount of energy, and vice versa, and it too changed the world.

His theory of relativity became one of the two pillars of modern physics, alongside quantum mechanics.

He left us 65 years ago this week, but Albert Einstein’s mind still shapes our world.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe