Gennaro Contaldo puts a bowl of penne in front of me. “Eat! Enjoy it!” he says. It’s 10am, but you don’t turn down pasta at an Italian chef’s house – no matter what time it is.

He made it from bits and pieces he found in his kitchen yesterday: Parmesan rind, carrot, a chunk of guanciale (cured meat), a jar of chickpeas, a shallot, celery, a potato, romaine lettuce – cooked down for 45 minutes with stock and served with a scoop of starchy pasta water and a glug of olive oil. Very simple, very tasty.

The 74-year-old says he throws nothing away. And not only for environmental reasons. In a cost of living crisis, throwing any food away is literally money in the bin. Knowing what you can do with leftovers is the key to cutting your food bill, Contaldo believes.

“If people knew how to cook, they would save at least half – at least!” he says. “I press everyone to learn how to cook because once you’ve learned how to cook, you can use whatever you find in the house.”

Classic Italian cooking, at its very heart, is cost-effective. The basis of many of the most famous dishes is known as “cucina povera” literally translating to “poor kitchen” or “poor cooking”. The chef says: “There was not much, so whatever you had you cooked in many different ways and nothing used to be thrown away.”

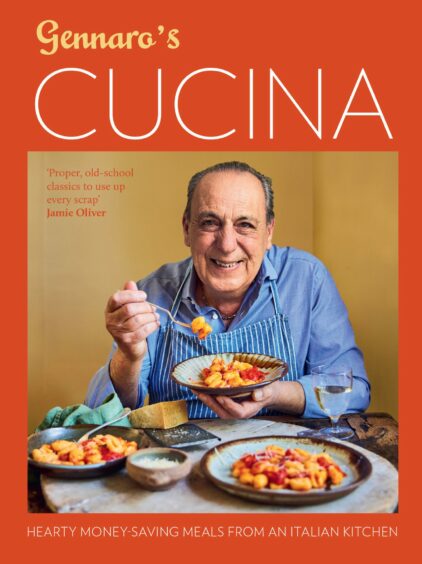

This is reflected in his latest cookbook, Gennaro’s Cucina, which focuses on hearty, money-saving meals, or, as he puts it “proper Italian cooking: few ingredients, maximum flavour”.

Pasta is the ideal vessel for odds and ends languishing in your fridge, insists Contaldo. “If you go to a restaurant, fresh tomato pasta, costs £11 or £12. From the market one bowl of tomatoes is £1 because they’re off the vine and they’re very good,” he says.

“Tomatoes, I can do in five minutes, I do a beautiful sauce. Cook them with a little bit of olive oil, a crush of garlic, a little bit of chilli, a little bit of water, boil the pasta at the same time, throw in the starch – if you’ve got some breadcrumbs, throw them on top.”

In the Contaldo household in London, where bunches of tomatoes hang from hooks around his kitchen/diner (“they become very sweet and last at least a month”), a meal will last several days. People chuck away leftovers far too soon, he says.

“If you do roast chicken, do you know how much stuff you have left? Remove a bit of meat, chop it up and do some kind of ravioli, boil it, then serve it with the same gravy as you had for roast chicken.

“When you think you can’t do anymore – get that chicken, celery, carrots, carcass, put it in water, boil it, you get chicken stock.”

Beans, lentils, chickpeas and bread all play an important part in this way of cooking. From passatelli in brodo (breadcrumb and Parmesan pasta) to acquasale (bread salad) and even padding out beef meatballs – or mondeghili – with stale bread to make the mixture stretch.

“And I hate expiry dates, just smell it, look at it – there’s nothing wrong with it except when it’s rotting. Even if you’ve got some milk left, when it goes sour you’ve got lovely ricotta.”

He won’t touch out of season fruit and veg flown thousands of miles to give us year-long supermarket produce. “Cherries are everywhere at the moment – when I see them in a shop, I won’t even taste it,” he says.

Contaldo grew up in the village of Minori on the Amalfi coast – “the sea was my swimming pool and the mountains were my back garden” – and fondly remembers artichoke season. “Everybody uses them, we enjoyed making it in many different ways,” he says. “And then when the season is finished… Something else comes to the market. We remember those beautiful days when we sat altogether eating artichoke but when it’s finished, we leave it, we forget about it, we wait for the next season – and look forward to it.”

Contaldo’s family’s business was selling linen, but food was intertwined with all aspects of life. “We had to go around up the hills and mountains to collect money, because not everyone paid you. Many times, instead of taking money, you take a chicken, a goat, salami, cheese, fruit, in exchange,” he remembers, laughing.

He learned to cook because, everyone did. “Inside my house papa wanted to cook, grandfather wanted to cook, grandma would cook, my mama would cook, my sister was taught by my grandma.

“There was no information, not many people wrote recipes down – I have a recipe book here,” he says, tapping his head.

“The Italians are very proud of whatever they make, they express themselves through food. You see them at the table, ‘Try this’, ‘Try that’, they love feeding you.”

Parmigiana di zucca

Parmigiana was originally made with aubergines from southern Italy, says Gennaro Contaldo. “Where aubergines are abundant during summer, pumpkin is plentiful during the colder season, especially in rural locations where this autumnal squash provided necessary nutrition for families.”

You’ll need:

- 1 x 1.4kg pumpkin (you need approximately 1kg prepped weight)

- 3-4 eggs

- Plain flour, for dusting

- Abundant vegetable oil, for deep-frying

- 2 balls of mozzarella cheese (each about 125g), drained and roughly chopped

- 75g grated Parmesan cheese

For the tomato sauce:

- 2tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 3 x 400g cans chopped tomatoes

- 6 basil leaves

- Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Method:

First make the tomato sauce. Heat the olive oil in a saucepan, add the onion and fry over a medium heat for about five minutes, then add the tomatoes, basil leaves and some salt to taste. Leave to simmer over a gentle heat for about 25 minutes until thickened.

In the meantime, peel the pumpkin, cut it in half, then into quarters. Remove the seeds and then cut into slices about five-millimetres thick. Lightly beat the eggs in a shallow dish with a little salt and pepper. Dust the pumpkin slices with flour, shaking off the excess, then dip into the beaten egg.

Heat plenty of vegetable oil in a deep frying pan until hot, then add the pumpkin slices (you may need to do this in batches, depending on the size of your pan) and deep-fry for a couple of minutes on each side. Remove using a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen paper to absorb the excess oil.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 200°C/180°C fan/gas mark 6.

Line an ovenproof dish with a little of the tomato sauce, then place some pumpkin slices over the top, sprinkle with a little black pepper, dot around some mozzarella, sprinkle over some grated Parmesan and top with some more tomato sauce. Continue making layers like these until you have finished all the ingredients, ending with a final sprinkling of mozzarella and grated Parmesan.

Cover with foil and bake in the oven for 15 minutes. Remove the foil and continue to bake for a further 15 minutes until the cheese has melted and has taken on a golden brown colour. Remove from the oven and leave to rest for about 10 minutes before serving.

Gennaro’s Cucina: Hearty Money-Saving Meals From An Italian Kitchen, photography by David Loftus, Pavilion Books, £25

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © PA

© PA © David Loftus / PA

© David Loftus / PA