George VI never dreamt of becoming king and, forced on to the throne by his elder brother’s December 1936 abdication, fell into his mother’s arms and sobbed like a child.

He did not believe himself up to the job and feared the Crown might not even survive the shock of Edward VIII’s dereliction. Many others had doubts, too.

The new sovereign had never in his life seen a state paper. He was by temperament low-key, retiring and shy. He suffered from a speech impediment, was of barely average intellect and, in the event, reigned for barely 15 years, dying in his sleep in the small hours of February 6, 1952.

Yet, 70 years later, this shy man is regarded as one of our greatest kings – diligent, courageous and vulnerable, who rose to all that was expected of him because it was his duty, head of the nation throughout the Second World War and all the changes and privations that shortly followed it.

His birth, a second son for the Duke and Duchess of York, was ill-timed. The baby arrived on the darkest 1895 date in Victoria’s diary, December 14, the anniversary of the death of Princess Alice, her second daughter, and, worse, that in 1861 of Albert, the prince consort.

His parents made the best of it by naming her latest great-grandchild Albert Frederick Arthur George, and he would be “Bertie” to his family all his days. But he would always be in the shadow of big brother Edward – whom Bertie simply assumed, from an early age, was better and smarter than he was – and could expect scant succour from his chilly parents.

Such was the temper of their father – who would assume the throne in 1910 as King George V – that it was not unknown for one of them to faint on peremptory summons to his study. All his four surviving boys would be heavy drinkers, and they could look for no sympathy from their mother, so offhand as to their welfare that she failed to notice their crazed nanny was torturing Edward and neglecting Bertie’s feeding.

Worse, he was forced to sleep in agonising splints – his father was worried the boy would grow up bow-legged – and, though naturally left-handed, young Bertie was compelled to write with his right hand. This so wrecked his confidence he came bottom of his class at Dartmouth Naval College and likely begot the stammer that would plague him for years.

But, unlike his elder brother, Bertie was allowed to see active service during the Great War, weathering the Battle of Jutland as “Mr Johnson” aboard HMS Collingwood. He was the first member of the royal family to serve in the RAF and the first to qualify as a pilot. He was taller and better looking than Edward, with taut cheekbones and lustrous eyes and he was a gifted tennis-player, even competing at Wimbledon.

As he embarked, in peacetime, on his royal duties, Bertie became interested in industry and he was not, in early manhood, quite the goodie-two-shoes of popular imagination.

The bachelor prince had a passionate affair with the actress Evelyn Laye, which he only ended on the promise of a Dukedom of York from his father – and, to some degree, he carried a torch for her for the rest of his life.

This, mused Cecilia Bowes-Lyon, Countess of Strathmore, to Queen Mary was “a man who will be made or marred by his wife.” Unfortunately, the girl he wanted – her own daughter, Elizabeth – was loath in her early 20s to join the royal goldfish-bowl.

Once, twice, and even thrice Elizabeth turned Bertie down. Bertie was pressed to try again. Finally, in January 1923 and at the fourth time of asking, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon accepted her prince and their Westminster Abbey marriage followed on April 26. Clergy refused to allow a BBC “wireless” broadcast of the service. Men might listen to it in pubs with their hats on, one harrumphed.

The marriage was the best decision Bertie ever made. Elizabeth was an instinctive and bewitching star. She brought to their union the confidence and perspective he lacked, and swiftly crafted an image – this cooing little turtle-dove of a woman – at odds with the steely and often formidable reality.

Though sensibly trimming their lifestyle as the Depression bit – the Duke gave up hunting – they enjoyed a splendid London townhouse, 145 Piccadilly, and made a country home of Royal Lodge in Windsor Great Park.

It was also at Elizabeth’s gentle insistence that Bertie – whose speech impediment no expert had managed to fix – sought the services of Lionel Logue, a friendly Australian who marvelled at the grit and perseverance of his patient.

Though Bertie never quite rid himself of an occasional hesitancy, the dreadful stammer he did eliminate and his Christmas broadcasts make moving listening today.

And, with their two little girls, Bertie and Elizabeth may have enjoyed a leisured Enid Blyton lifestyle but for George V’s unexpected death in January 1936 – at the height of Edward’s infatuation with Wallis Simpson.

In the event, Bertie had scarce a fortnight’s warning of the abdication and had difficulties in even securing a meeting with the King. Meanwhile, so low was establishment confidence in Bertie that serious thought was given to bypassing not just him but his younger brother, Henry, the charisma-free Duke of Gloucester and bestowing the crown on George, Duke of Kent instead.

Kent was assured, clever, and had a male heir. But his past would not have borne close scrutiny – to this day, the Palace has never permitted an official biography – and Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin scuppered the idea.

But there would be no King Albert. Bertie deliberately chose George as his regnal name to stress continuity with his late father and on May 12, 1937 he and Elizabeth, not Edward and Wallace, were crowned King and Queen.

With support from Logue, the new King negotiated the oath with aplomb and that evening made an assured radio broadcast.

“It is with a very full heart that I speak to you tonight,” he declared. “I cannot find words with which to thank you for your love and loyalty to the queen and to myself. Your goodwill in the streets today, your countless messages from overseas and from every quarter of these islands has filled our hearts to overflowing.”

Whether consciously or otherwise, George VI was never afraid to show a little vulnerability in his speeches and, as Queen Mary tartly observed when someone unwisely spoke of Edward’s great loss, her second son was the one making the sacrifice.

He and his family had been forced to quit the home they loved for vast, impersonal Buckingham Palace. After years of gentle duties, the new King had twice-daily to wade through boxes of official papers.

Their privacy was gone, they had to travel incessantly and Elizabeth had even, for the first time, to have her ears pierced: full, bejewelled splendour was expected of a queen consort.

And, of course, there was always Edward, forever on the telephone with good advice, whether the new King wanted it or not.

George VI reached a generous financial settlement with the new Duke of Windsor, only subsequently to learn that the late king had lied about his personal fortune. At last, he snapped – or Elizabeth put her foot down – and gave orders that calls from his brother were no longer to be put through.

He further decreed that, on their marriage, Wallis was not to be granted the style and dignity of Her Royal Highness. It was petty and probably illegal, but it had one merciful result: the indignant couple would never make their home in Britain.

There was nothing, Edward would painfully learn, quite as “ex” as an ex-king. “My predecessor,” George VI once observed darkly, “is not only alive, but very much so.” Their old, warm bond would never return.

It took time for the new King and Queen to find their feet and Edward remained ominously popular but he and his consort did themselves no favours with an ill-judged tour of Nazi Germany, whereas state visits of George VI and his queen were a signal success.

That, to France, became a matter of great alarm when the Queen’s mother died on the eve of their departure. She could hardly hit Paris with the glamorous outfits got up by Norman Hartnell. But nor could she meet the French in funereal black.

However, white is also an approved colour of mourning, so Hartnell ran up another wardrobe in white – and the French loved it.

Their 1939 tour of Canada and the United States was still more sensitive. But the Americans, still a little cross about Mrs Simpson, took quickly to this glowing Queen and her smiling, unassuming husband – who so enjoyed hot-dogs with the Roosevelts that he asked for a second helping.

Indeed, George VI made a conscious decision to foreground his wife, working with photographer Cecil Beaton and others to glamorise her image and find the styles that best suited her. And, when war finally came, there was no question of retreat into the countryside, far less the safety of, say, Canada.

“The children cannot leave without me,” declared Elizabeth, “I cannot leave without the king, and the king will never leave.” Though the princesses were consigned to Windsor, George VI and his Queen braved Buckingham Palace every day, even at the height of the Blitz.

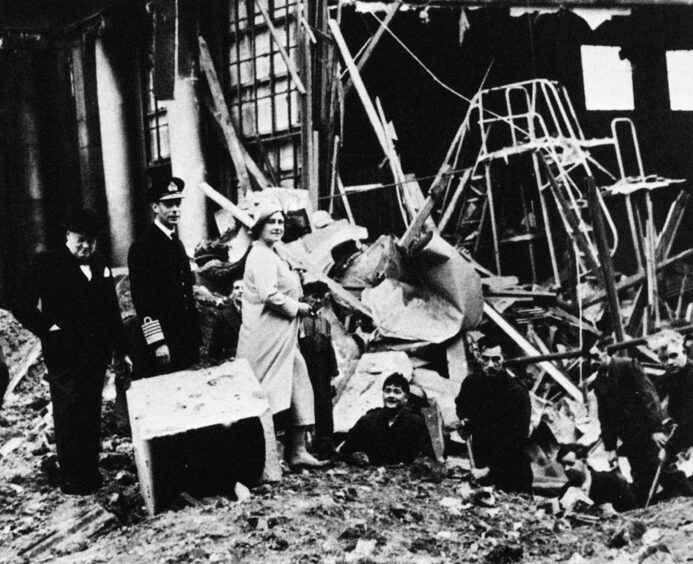

They put up assorted continental royals who had fled the Nazis and, for the duration, George was never seen out of uniform and Elizabeth was never seen in it. She also practised using a revolver – “I won’t go down like the others” – and they were fortunate to escape injury when Buckingham Palace was bombed, in broad daylight, on September 13, 1940. They watched, incredulous, from a window and, had it not been open, the flying glass could well have killed them.

Initially distrustful of Churchill, who had rooted for Edward during the abdication crisis, George VI came to profound regard for him. He nevertheless, from 1945 and with equanimity, coped with a radical new Labour government – and, with her independence, the loss of his title as Emperor of India. He was also, till 1949, the last King of Ireland.

By temperament George VI was highly strung, a worrier, prone to explosive “gnashes” of temper. He was also a heavy smoker and, latterly, so grey and ashen he donned make-up for public appearances. By 1947, when “Us Four” made an arduous tour of South Africa, he was already unwell. Even so, when Elizabeth and Philip married that November, they could have reasonably hoped for decades of relative privacy before ascending the throne.

It was not to be. By 1951 they were forced to return from Malta as the ailing king underwent lung surgery and pulled out of a projected, 1952 tour of Australia and New Zealand. Perhaps only the Queen knew how ill George VI really was. He was still so weak that December that his Christmas address had for the first time to be pre-recorded – in stages.

Yet, on February 5 that year, he enjoyed a blissful day of shooting in the frosted fields of Sandringham, and retired to bed exultant and happy. A guard saw him fumbling with the catch of his window, later that night. And, sometime in the small hours, the king’s tired old heart stopped beating. He was 56.

It was a tragedy for his widow, who for some months gave real thought to entire retirement from public life. A tragedy for Princess Margaret, who never really recovered from losing her father so young. And a tragedy, arguably, even for Charles, made heir-apparent when still but three and thereafter granted very little of his parents’ time.

Nearly half a century later, reeling from the loss of her own husband, a lady-in-waiting asked the Queen Mother: “Does this ever get better?” “No,” she said flatly, “but you get better at it.”

To the end she blamed the Windsors, once – when someone mentioned the Duchess – snapping: “Ah, yes. The woman who killed my husband.” Yet Elizabeth never forgot the wreath from Churchill, among all the floral tributes at the King’s funeral. The card read, simply: “For valour.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe