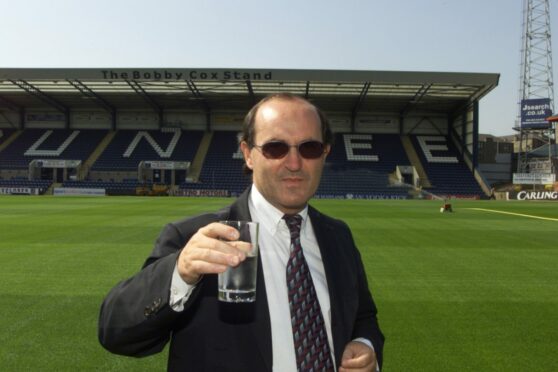

An international lawyer – the so-called Devil’s Advocate with a client list featuring some of the world’s most notorious despots and warlords – joining the board at Dundee FC was, even for Scottish football, unusual.

Giovanni di Stefano’s arrival on Tayside in 2003 prompted fevered speculation of famous names like Paul Gascoigne, Edgar Davids, Georgi Kinkladze and Fabrizio Ravanelli joining the club.

However, it also linked the Dens Park team with some more infamous names on his roster of clients, from Serbian war criminals Arkan and Slobodan Milosevic to Robert Mugabe and Saddam Hussein.

The wheeling-dealing lawyer who had, it would later emerge, no legal qualifications at all, careered through the ’90s and noughties making money and headlines in equal measure.

However, a forthcoming documentary about di Stefano charts how his career, like his time on Tayside, ended in ignominy. When he arrived at the club, di Stefano promised high-profile international footballers, stadium renovations and success on the park; he left behind him a club facing collapse less than six months later.

Prior to joining their board, there were questions about di Stefano’s suitability to be a director of Dundee. A failed bid to buy a stake in the Dark Blues in 1999 had brought him to the attention of UK authorities who had issued an arrest warrant for fraud dating back to the early ’90s. He was extradited but the case collapsed and finally he was appointed to the board in August 2003.

“As far as I was concerned, he was a lawyer,” said Jim Duffy, Dundee manager between 2002 and 2005. “There are a lot of lawyers who defend criminals and people who have done bad things. They’re there to do a job, not be morally judged.

“It wasn’t my job to go and scrutinise his career. As far as I was concerned he was a lawyer and that allowed him to facilitate an investment into the club. Ultimately that proved not to be the case but I wasn’t an investigative journalist, I was managing Dundee.”

Once on the board, di Stefano moved quickly to boost the club’s standing by instructing the manager to bring in box-office names.

“He wanted to deliver a new, higher profile for the club, and also for himself,” said Duffy. “The best way to describe Giovanni was he was enthusiastic, self-assured and confident. That air of confidence was part of the reason people would believe he could deliver on some of the things he came up with.

“He would throw names into the hat. Paul Gascoigne, Edgar Davids or Georgi Kinkladze.”

Gascoigne came to the club for a day, according to Duffy, and the pair talked about good fishing spots near the city. The deal ultimately fell through.

Eventually the club signed Craig Burley, a former Chelsea and Celtic star, and Italian forward Ravanelli, who in 1997 had become the highest-paid player in the UK at the time when he joined Middlesbrough from Juventus in an eye-watering deal worth £47,000 per week. “Players and supporters got to feel this huge interest in the club, coming from around the whole of the UK and further afield,” said Duffy.

The Scottish Football Association refused to acknowledge di Stefano, with his chequered history and criminal convictions, as a fit and proper person.

However, Duffy recalled di Stefano wasn’t a difficult figure behind the scenes.

“For all the stories about him he wasn’t a fiery character,” he explained. “He almost seemed quite unassuming at times.

“He obviously liked publicity, and liked the fact cameras and TV were coming to speak to him. He enjoyed that side of it but I can’t remember him losing his temper.”

It hardly mattered given the dire straits in which the club, with its highly-paid squad, found itself. Attracting the size of crowds which could help pay for a star-studded team never happened – the average home attendance that season was 7,000. The club was losing £100,000 per week. Dundee’s board were forced to place the club into administration, and 15 players were released, including star striker Ravanelli.

Administrators immediately terminated the contracts of 25 out of 70 full-time members of staff. “When it comes to football clubs going into administration and staff losing their jobs, it’s horrible. Horrible. Like in any industry,” said Duffy.

“There were elements of the club he was part of, but it wasn’t all down to him. He put himself into situations which weren’t strictly true, he was giving people false hope. If you have got good intentions and you give people belief and it’s your money then it’s up to you, you can spend it how you like.

“But if you’ve not got the money and you’re leading people on, that’s wrong.

“Football clubs mean so much to fans. And when they’re left hanging on by their fingernails it’s up to the supporters to rally round and save the club.

“The devastation left behind was the hardest thing to experience. A director who’s a fan can see what it means to supporters. And someone like di Stefano could just walk away.”

Di Stefano was forced out of the club in 2004 but he wasn’t out of the headlines for long after appearing on television later that year claiming to be working on behalf of deposed Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

Yet questions over his legal qualifications persisted and in 2011 he was arrested and two years later at Southwark Crown Court he was convicted of 25 counts of fraud and deception.He was jailed for 14 years.

Di Stefano’s career was built on shifting sands and false promises like the ones he had made to fans of Dundee.

“He came out with a few bold and brash statements about investing millions in players,” added Duffy, who also managed Hibs and Falkirk, among other clubs. “People enjoyed that aspect of him, especially the fans. They wanted to believe somebody was going to take the club to the next level.

“He had an air of confidence about him. He was a director and as manager I couldn’t say, ‘Well, I don’t believe you’.”

Make-believe lawyer who asked if Satan had a case

He was nicknamed the Devil’s Advocate but no one expected Giovanni di Stefano to take it literally. However, after representing dictators, despots and warlords, the international lawyer, who never studied law, said the Devil would be just another client: “No one’s ever asked, does Satan have a case?”

Yet he hardly needed to dream up hypothetical defences for others when his own client list featured some of the world’s most notorious villains.

In the 1990s, di Stefano became the legal representative of Zeljko Raznatovic, better known as Arkan. He led a Serbian paramilitary group, Arkan’s Tigers, who massacred thousands of civilians after the break-up of Yugoslavia.

The pair bought Serbian team Obilic and took them to the Champions League amid allegations of match fixing. Arkan was assassinated in 2000 while awaiting trial at The Hague.

Di Stefano also claimed to be friends with Yasser Arafat, Gerry Adams and Saddam Hussein.

“Well I don’t have coffee with him or talk about girls or football, but I have had the honour of meeting his excellency President Saddam Hussein several times, and I find that he is an extremely logical and hard-working man,” he said in 2002.

When Hussein went on trial, di Stefano appeared on television saying he was helping his defence.

He also claimed to have met Osama bin Laden in Baghdad in 1998. “I found he had a handshake like a priest. Warm,” he said.

Di Stefano, who may be released from a long prison sentence for fraud next year, may not have been qualified but loved the law: “Some people take mistresses, some people have polo ponies, some people play bridge, some people like football, some people like collecting stamps, some people enjoy ornithology. I like the law. What’s wrong with that?”

Devil’s Advocate: The Mostly True Story Of Giovanni di Stefano launches on Sky Documentaries on February 15 at 9pm

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SNS Group 0141 221 3602

© SNS Group 0141 221 3602