They were brave, adventurous women ahead of their time and determined to break through barriers to make their mark in a man’s world.

It was a long, tortuous struggle but the talented artists known as the Glasgow Girls were ready to fight for recognition and, at the turn of the last century, they achieved their aim.

Sadly, after their talent was briefly recognised, they sank into obscurity, their groundbreaking work shunned by the art world.

While the critics of their time quickly forgot them, I never could …ever since attending an exhibition of this pioneering group of women artists, students and teachers at Glasgow School of Art in 2010, which marked 10 years since their first retrospective exhibition.

I was swept away by their romantic book illustrations and embroidered panels, their striking paintings and metalwork, and jewellery studded with enamel and semi-precious stones.

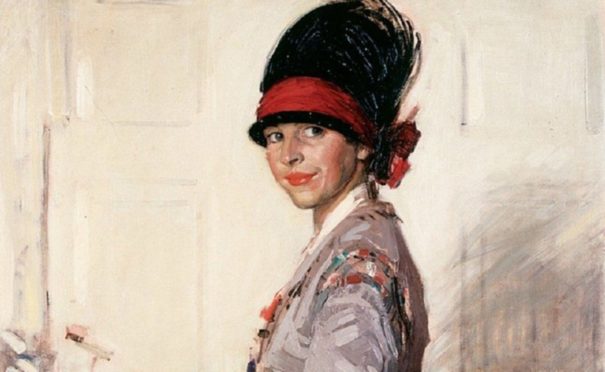

One artist in particular caught my eye: Eleanor Allen Moore, whose self-portrait was chosen for the exhibition poster. Bright-eyed and full of spirit, I had to find out more about her, and wasn’t disappointed by her tumultuous story and incandescent talent.

Her amazing life inspired my new novel Daisy Chain, whose heroine, like the real artist, attended Glasgow School of Art before travelling to China with her husband, a doctor, and their daughter.

I jumped at the opportunity to research her life in the Far East when a Society of Authors grant allowed me to travel to Shanghai and explore the exotic and sophisticated older parts of the city Eleanor frequented and which remain largely intact – from European-style villas and tree-lined boulevards of the French settlement to the imposing grandeur of the trading houses, banks and grand hotels on the Bund.

Walking the same streets of Shanghai as Eleanor, and experiencing the same sights, smells and sounds, gave me a unique insight into the rich, eventful life of this intrepid woman.

The city, known as the Paris of the East, was notorious for its pleasure-seeking denizens, the wealthy taipans who ordered champagne by the crate when it came to their round at the Long Bar in the Shanghai Club, and who amused themselves at the races and swanky nightspots where jazz bands played through the night.

But these were also times of political upheaval in China, when foreigners were confined to the safety of the International and French Concessions. Shanghai in the 1920s was a dangerous, lawless place, its criminal underbelly run by vicious gangs, or tongs. Eleanor’s husband was even kidnapped once but managed to escape from the kidnappers’ car with a bullet hole through his coat.

Daringly, as a foreign woman, Eleanor braved Shanghai’s Chinese old town and ventured into the notorious opium dens to sketch those smoking inside, as well as street scenes of ordinary Chinese people going about their business.

Her independent spirit and courage were typical of the colourful Glasgow Girls, profiled here, who clashed with respectable society, and I brought elements of their strong characters into my novel, which spans a period of dramatic change from 1909 to 1929 and moves between Kirkcudbright, Glasgow and Shanghai.

Daisy Chain by Maggie Ritchie will be published by Two Roads on Thursday.

Margaret Macdonald

One of the most prominent and earliest of the Glasgow Girls was Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s wife Margaret Macdonald.

She was one of the female artists encouraged to take up a place at Glasgow School of Art by the forward-thinking director, Francis Newbery, who led the way in education reform and provided equal opportunities for women. In his time, 50% of the students at Glasgow School of Art were female as was 30% of the staff, highly unusual in that period.

Margaret and her sister Frances, along with Frances’s husband, Herbert McNair, and Mackintosh, were known as The Four and were at the forefront of the Glasgow Style – a version of Art Nouveau that was taking Europe by storm. Their unusual designs and paintings of elongated, melancholy figures led the sisters to be dubbed the Spook School.

The Four’s projects included the Willow and Ingram Street Tea Rooms in Glasgow, and The Hill House in Helensburgh, and their work was exhibited in Vienna and Turin.

Frances had an unhappy married life with McNair, an architect, who drank and had financial difficulties after his career floundered. Her family shipped him off to Canada on a one-way ticket, only for him to return to Glasgow. Her death in 1921 may have been suicide and, shortly after, her husband destroyed much of her work.

Bessie MacNicol

Bessie MacNicol’s life was also tragically cut short when she died in childbirth one month before her 35th birthday. I borrowed her talented style of portraiture for my heroine in Daisy Chain, and a touch of her spirit too, shown in a letter to her friend, the artist E A Hornel, one of the Glasgow Boys whose portrait she painted.

“I have got a new kind of cycling skirt, which is divided, so far up, but is just like a walking skirt. I put the Mater into fits when I was in the shop buying it, by dancing a hornpipe behind the woman’s back. They are like wide Jack Tar ‘bags’. I am getting on splendidly and am quite a scorcher. I have not gone more than 10 miles yet but can pass machines and people without running them down for certain.”

Norah Neilson Gray

Norah Neilson Gray’s powerful paintings from the First World War – some of

which can be seen in Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow – were the inspiration for scenes from that turbulent period in my novel.

Gray, born in Helensburgh in 1882, went to France to work as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse for the Scottish Women’s Hospital in a French Red Cross hospital in the Abbaye de Royaumont in 1918, when the hospital was often bombed.

She painted during the day, after night duty, sketching injured soldiers, doctors and nurses in the abbey cloisters.

After the war, Gray, who as a student at Glasgow School of Art had exhibited at the Royal Academy, was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum to record the staff at the hospital.

Jessie M King

Jessie M King, best known for her book illustrations of fairy tales, became a familiar, if eccentric, figure in the artists’ town of Kirkcudbright.

Riding her bicycle in a cape, voluminous black hat and silver buckle shoes, she was often followed by the village children who she befriended and who saw her as a “friendly witch”.

A romantic who believed in magic, as a young woman lying in the grass one summer, she felt a pricking sensation on her eyelids and believed she had been chosen by the fairies to communicate their world to others. Jessie, a friend of E A Hornel, who lived nearby, converted the cottages in the lane behind her home to studios and rented them out to artists. It became known as the “Green Gate Close Coterie”, a community of women artists who scandalised the townsfolk by swimming naked in the burn at the bottom of Jessie’s garden.

Annie French succeeded Jessie M King to teach the design element in the ceramics class at Glasgow School of Art. Compared to Aubrey Beardsley and the Pre-Raphaelites by her admiring contemporaries, the critics were not so kind to this woman artist – her pen and ink drawings of maidens among flowers or woods were described condescendingly as “quaint”.

From the book

An extract from Daisy Chain, the new novel by Maggie Ritchie.

As Lily settled at Glasgow School of Art, she gradually shed the remnants of her old life. First to go were the tight corsets that had stifled her breath, replaced by billowing, gloriously loose dresses in the aesthetic style that she made herself and decorated with embroidery, felt flowers, beads and winking circles of mirrored glass.

Her stitches were still uneven but the patient needlework tutor had encouraged her to use wool on calico, so the rustic effect was pleasing, and had reassured her that while others, such as Kit, were skilled at recreating scenes from fairy tales and Arthurian legends, it was enough to make honest, workaday clothes that honoured the arts and crafts principles laid down by William Morris.

Lily now wore her coppery hair softly gathered at the nape, ignoring the scandalised looks from conventionally dressed women in the streets and the sneers of men rushing to their office jobs in their monochrome work suits.

It had taken some courage at first to step out without a hat, her unpinned hair flowing down her back in waves like the pre-Raphaelite beauties so admired by her new friends, but she found that she could weather the disdain – what did it matter to her what anyone thought? She was an artist now and would dress as she damned well pleased.

Her landlady had got to her, though, glaring at her when she returned, and talking loudly on the stairs outside her room about the loose morals of young women today and the trash she was forced to take in to earn a crust, despite Lily following the rules pinned to her door that included no men callers.

When Kit told her she’d found a studio flat in a Garnethill tenement, only a few minutes’ walk from the Mack and cheaper than both their lodgings if they shared, Lily readily agreed to move in with her.

‘You’ll come to a bad end, that’s for sure,’ the landlady sniffed.

‘So I’ve been told,’ Lily said…

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied