Their intricacy and exquisite detail belie their birth in heavy industry but glass ships in bottles enjoyed a brief but passionate popularity in Britain.

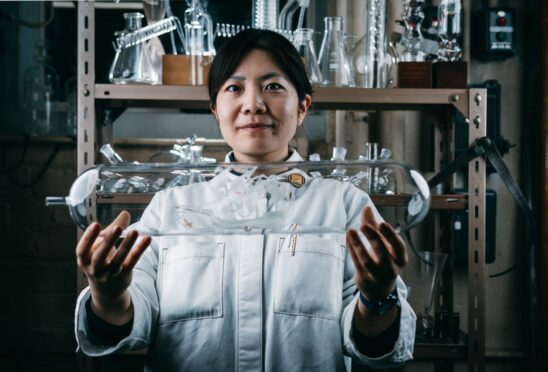

The story behind their launch combines, according to Ayako Tani, the tenacity of traditional skills, entrepreneurial spirit and workers’ resilience and is one she is determined to tell.

In the early 1970s, as heavy industry declined, scientific glassblowers who found themselves out of work began to make glass ships in bottles, and what started as a cottage industry led to a highly viable commercial enterprise, in some cases doubling the wages of the workers and providing their families with a better life.

But as mass production took over and business was outsourced to China, coupled with a change in consumer tastes, UK manufacturing came to an end.

Today, scientific glassblowing in the UK is categorised as endangered by the Heritage Crafts Association, with between 100 and 200 professionals in employment.

One of them is Tani, who works at Glasgow University’s school of chemistry. For the past several years, she has dedicated herself to recording the stories of the redundant industry workers who began making glass ships in bottles, believing it to be an important part of recent history that was in danger of being forgotten.

Ahead of a talk she will give at the Scottish Maritime Museum, where she currently has an exhibition of glass ships in bottles, she explained why she feels it is essential to remember the industry. “I want to share the story of people’s resilience, where their factories closed but they applied their skills to something else and made it very successful,” she said. “I think it’s an inspiring story.

“For those who were part of it, I don’t think they realised the significance of what they did, of how they survived after losing their factory jobs, but I felt it had to be archived for the future. I wanted to show the inclusivity of the society to notice their own value and grow something new.”

Originally from Tokyo, Tani moved to Sunderland in 2014 to study at the city’s university and it was at the associated National Glass Centre where she met some of the ex-workers of the closed Pyrex factory who turned to manufacturing glass ships in bottles. “When I finished university, I started working with local glassblowers and as we worked together they reminisced about how they used to work for the Pyrex factory in Sunderland, which started to downsize in the ‘70s. The first group of people – four senior glassblowers – were made redundant in 1972.

“They said they did any job they could, be it scientific, ornamental swans, glass ships in bottles, and they found the latter was the most commercially viable, and soon they were receiving big orders. Workshops were set up, and as time went on, their previous colleagues from Pyrex joined them.

“Many of them said they didn’t have to worry about their next job, as they knew the glass ships in bottles were waiting for them. For some, their wages doubled and they were able to do things like buy their first car. It was really profitable for a short time.”

Eventually, mass production and big business moved in, and manufacturing moved to China in 2005.

“I heard all of these stories as I worked alongside them but it wasn’t a case of saying to me, ‘Listen, this is important’, because it was too close in their living memory. I come from the other side of the globe, so I noted its significance.”

Tani immersed herself in the craft. She completed a PhD in the subject and began a project, Vessels Of Memory, where she interviewed former workers, compiling a website and a book on the industry. She has also collected a large number of glass ships in bottles, some of which are on display at the Scottish Maritime Museum in Dumbarton, and she has also become accomplished in the craft herself.

“Most of the workers are retired now but one, Brian Jones, is still working at the National Glass Centre and he more or less taught me all the techniques and introduced me to his friends and colleagues to interview.”

There was no family background in glassblowing for Tani; it was only a lack of career options in her home country that has led her to Glasgow, via residences in America, China and Sunderland. “I grew up in the middle of Tokyo and I didn’t know about glassblowing at all. The only career path option as a student was to become an office worker – that was my first career. I knew I definitely wanted to do something else. I discovered the Tokyo Glass Art Institute.

“It’s not a university or school, but it was something I did as a weekend hobby while I was working full-time.

“I decided to do it seriously and that’s when I came to Sunderland. When I finished university, I started working with the local glassblowers and that’s when I found out about glass ships in bottles.”

Her job at Glasgow University, she believes, is as a result of her passion for glass ships in bottles and now Tani is about to donate two models from her collection to the V&A Museum.

How it’s done

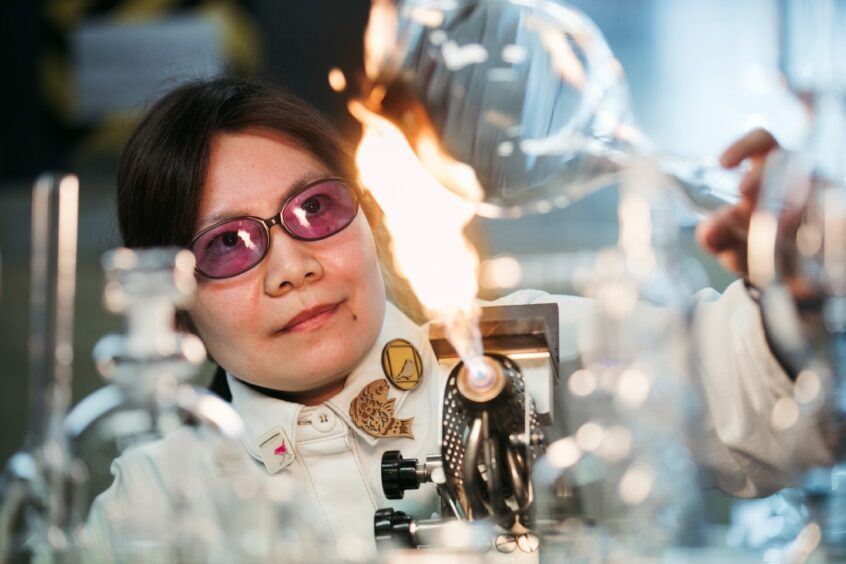

Glass ships in bottles are made of borosilicate glass, which is strong against thermal shock.

The sails of the glass ships are usually made of glass tubes sliced into small sections, with the curved surface of the original tube depicting billowed sails. Thick rods are used for the ships’ body and thinner rods for the masts, while larger tubes are used to make the bottles. The sails are fused to the masts and then the masts to the body, while extra detail can be made using items like metal files and screws.

The ship is placed inside via the open bottom and a vertical flame is used on the spot to make sure the join is smooth, and then the bottom is closed.

For an experienced glassblower, and depending on how simple or elaborate the design is, making a glass ship in a bottle would take a minimum of half a day.

Glass Ships In Bottles Exhibition, Scottish Maritime Museum, Dumbarton. Ayako Tani will deliver hour-long tours at 11am and 1pm on May 14 to mark the end of the exhibition.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley