Port Glasgow has a rich shipbuilding history, but that seems a generation ago.

The launch of the ferry MV Glen Rosa last Tuesday reignited that pride just for a while.

A member of one local family observes the impact…

When he landed a job as an apprentice grocer in the Port Glasgow Co-Op as a teenager, my father told his shipbuilder dad that he didn’t feel like a worker because his hands weren’t dirty.

My grandad’s response to his teenage son in the 1950s was incredibly prescient.

“They won’t always build boats here,” he told him. “But they’ll always need to eat.”

Now the shore along the lower Clyde, where generations of men once built generations of ships, has become a junk-food highway of drive-through takeaways, where the calories are as high as the old Goliath crane and the dismal order sheets are for Big Macs, not big boats.

Sixty years later, Tommy English’s prophecy is true. But there are no grocers stores where he worked, instead a McDonald’s, a Burger King and two Costas, with more still to come. Only one shipyard remains in this post-industrial town in the most deprived council in the country – a town being encouraged to eat itself behind the wheel of a car by the powers that be.

Yet in Port Glasgow on Tuesday, the supermarket car parks that cover the yards’ footprint were full, and it wasn’t for the shopping.

At 1.40pm, this old, storied shipbuilding town cranked into gear once more, slipping a boat into the river from its one remaining shipyard. The launch of the Glen Rosa, one of two CalMac ferries being built at Ferguson Marine, almost became the latest sorry chapter in a highly politicised story of government buy-outs, mismanagement and blown budgets which traduced the town’s great shipbuilding history dating to the 1800s.

After seven years of metaphorically stormy seas at Ferguson’s, Tuesday’s high winds whipped up literal ones, forcing a delay.

When she finally slipped into the white horses behind Newark Castle, there were cheers and tears. Some say The Skelpies, the town’s giant shipbuilder sculptures, threw up their arms in relief.

I come from a long line of Inverclyders who worked long, hard, dirty hours in the yards and factories supporting shipbuilding here.

My grandfather, Jimmy Breslin, was a gaffer in the town’s Gourock Ropeworks in the 1950s, servicing the boats with sails, canvas and rope, tragically dying in an accident at the mill in his 40s.

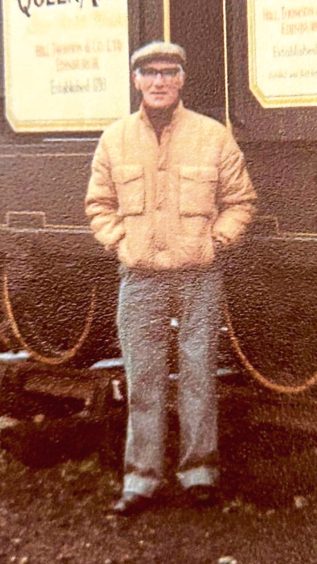

On the other side, Tommy, whose dirty hands his boy Jack envied, worked in yards the length of the river and bore the scars for years. My great aunt was a shipyard nurse. My grandmother was a mill girl.

Even now, the connection remains. Two of my uncles grafted on the ferries. One was on board for the launch.

There was something instinctive, defiant perhaps, in how Inverclyders came to witness an event almost every family in these towns has a historical, and emotional, connection to.

Maybe it was in testament to our forebears, an acknowledgment that our opportunities have been the fruit of their toils.

Maybe it was in tribute to the work of the men and women whose graft built these boats with quiet dignity while their overlords repeatedly holed them below the waterline.

Maybe it was simply in support of a place where the grassroots PortGlasgow2025 group is striving to give the townsfolk something more than a Happy Meal to celebrate on its 250th anniversary next year. Whatever it was, it wasn’t to mark the opening of the Greggs drive-through down the road.

Artist Stanley Spencer came to the town to paint life in and around the yards in the 1930s.

So too did Joan Eardley. They’d barely have recognised the place on Tuesday, save perhaps for the gusts of pride blowing up John Wood Street off the water as Glen Rosa launched.

Among the Port’s most-celebrated ships is Europe’s first paddle steamer, Henry Bell’s Comet, built in 1812. In 2020 its wreck was found off Oban and designated as a scheduled monument by Historic Environment Scotland.

A replica, which sat proudly at the heart of the town centre for decades, was neglected into disrepair. Its unceremonious demolition last year, within yards of three drive-through junk zones in the shadow of these two ferries, was too pointed a metaphor.

Yet, for a few hours on Tuesday, Port Glasgow threw off the epithets of deprivation and poor leadership, coming together by the thousand in hope and celebration of their forebears’ legacy, to remind itself of its identity as a town which built ships, now, as then.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe