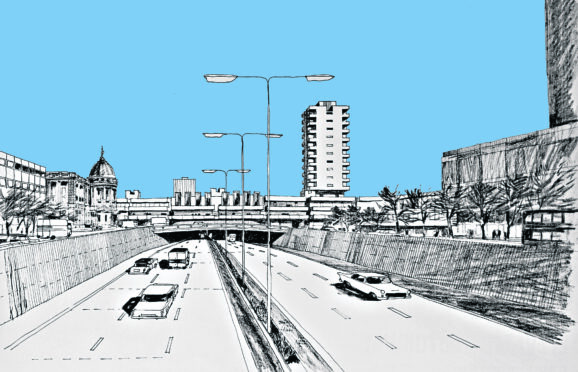

It is the busiest stretch of road in Scotland but is now, and will remain for years, the country’s most notorious traffic jam.

The stretch of the M8 scything through the centre of Glasgow to cross the Clyde at the Kingston Bridge is a more or less constant snarl-up as massive works to strengthen supports continue.

Motorists who can avoid it, do, those who can’t endure long delays around the Woodside Viaduct where lanes are closed and will remain closed for years with a £35 million schedule of essential works not expected to be finished before November 2023.

The long-running delays and expectation that more repairs will be needed when these are completed has given new impetus to the debate about modern transport systems, our dependence on cars and whether the unthinkable – getting rid of the M8 and other motorways around Scotland and finding a new way – should be thinkable after all.

Some experts say that the bridge and its surrounds, which opened in June 1970 and carries up to 90,000 vehicles a day, is no longer fit for purpose for a modern city.

They believe it is time to stop throwing tens of millions of pounds of public money at maintaining the crumbling infrastructure annually and replace it with sustainable and interconnected residential neighbourhoods that would promote public transport, walking and cycling.

Jude Barber, a leading urban architect and director of Glasgow-based consultants Collective Architecture, believes that due to climate change targets there has never been a better time to start rethinking the M8.

For a start, she thinks not enough good use is being made of the River Clyde and existing rail networks to shift goods and freight through the city and relieve pressure on roads. Major events such as last year’s Cop 26 climate change conference went ahead successfully while sections of the inner-city motorways were closed, which she said should signal that a sea change was possible.

“The cost of not decommissioning the M8 in Glasgow will be too high in relation to the long-term effects on people’s health and quality of life,” said Barber. “We have to start reimagining what Scotland’s cities would look like without ugly highways running straight into them.

“Some people would argue that if we got rid of the M8 it would simply put more pressure on suburban streets which would be required to handle the extra traffic but much of these worries could be eased by making much better use of our waterways and railway infrastructure to move goods around.

“We have some magnificent buildings in the Charing Cross area such as the Mitchell Library, which deserve significant public spaces in front of them, instead of being crammed up against a busy and dirty motorway.

“Making the city motorway a restricted speed area or even covering parts of it from sight altogether and building attractive urban spaces on top would be a start but we need to begin to think about this now as it would take a 10 or 20-year plan to turn it into reality. Changes to the motorway may mean that it takes a bit longer to get around but surely that is a small price to pay for transforming a city for the better for its residents and attract more visitors?”

Dr Andrew Hoolachan, a lecturer in urban planning at Glasgow University, points to successful transport regeneration initiatives overseas in cities such as San Francisco, Boston and Seoul as examples of a way forward for Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen.

In April 2020, as part of the city’s Covid-19 response efforts, San Francisco temporarily repurposed its Upper Great Highway to be a car-free street that prioritises families, cyclists and pedestrians.

The move has proved so popular with residents that last August, the highway was reopened to car traffic on weekdays only while remaining closed to vehicles during the weekends, starting on Fridays at noon.

In 1968, an elevated freeway covered up the Cheonggye Creek which ran through South Korea’s biggest city, Seoul, and hid the features of its historical waterfront.

Thirty years later, the surrounding area recorded the highest levels of noise and congestion in the city. Residents eventually agreed that the situation could not be improved without removing the freeway. The highway removal was completed in 2005, and in its place is an artificial creek that cuts a five-mile green swath through the centre of the city.

By building green corridors around the rediscovered waterway, Seoul has attracted affluent and educated workers and residents who appreciate the feel of a natural environment in an urban setting.

“Even Amsterdam, which is world-known for its canals, tram and bicycle routes was a congested mess with traffic in the 1970s before its transport systems were radically overhauled,” said Hoolachan.

“People in Scotland tend to think that we just don’t do that sort of thing here, but why not?”

The lecturer is so passionate about repurposing the M8 that he has introduced a module on exploring its removal for students doing a Master’s degree in urban planning.

“They have already come up with a raft of innovative ideas such as submerging parts of the city centre motorway at the St George’s Cross and Anderston areas and transforming them into vital and attractive places for people, instead of being there mainly to accommodate non-stop traffic.

“We need visionary leadership to turn this into a vital national project, not just in Glasgow but for our other big cities such as Dundee and Aberdeen too.”

Glasgow MSP Paul Sweeney believes we need to stop pouring tens of millions of pounds into maintaining the M8 around Glasgow and shed a long-held mentality within government that the motorway must be continually repaired, at any cost.

“We are just throwing good money after bad,” he said. “At what point are we going to have a sanity check about the damage this motorway is doing to the city and its residents. People are sick of all the delays and pollution it creates. And it is an eyesore.”

Sweeney believes a motorway-free city would soon pay for itself through rental income from localised retail outlets, increased tourism and housing in residential neighbourhoods that would spring up as a result of the transformation.

“It is a no-brainer but there seems to be little intellectual curiosity in the idea from government which simply continues with its traditional robotic response, which is to ‘fix the motorway’,” he said.

Transport Scotland, which is responsible for running the M8, said it recognised that noise and air pollution from major roads could impact quality of life, as well as our natural environment, and said it was working to tackle both issues. It insisted repairs on the M8 Woodside Viaduct were essential and it was working hard to minimise impact on local residents and businesses and keep traffic moving.

Glasgow City Council, meanwhile, insists the motorway is a significant part of the city’s transport infrastructure, adding: “The implications of removing the M8 would be substantial and would require careful and detailed assessment.”

The road is not without its fans or, at least, supporters. Martin Reid, director of policy at the Road Haulage Association in Scotland, said his industry was already working hard to meet environmental targets set by the Scottish Government around lowering emissions from vehicles but warned the M8 at Glasgow was vital for connecting Scotland to the rest of the UK and beyond and to keep freight moving.

“We can’t make changes to this network without concrete and workable alternatives and so far, there isn’t one,” he said.

Neil Greig, director of policy and research at the Institute of Advanced Motorists in Scotland, said any repurposing of the Kingston Bridge and M8 would likely mean heavy lorries and traffic being rerouted through suburbs, causing chaos on narrow roads.

Meanwhile, he fears the recent construction of extra cycle lanes and foot pathways in and around Glasgow is slowing traffic while not making it any easier to move around the city. “We will be hearing more ideas about repurposing the M8 as the government tries to cut omissions by 25% by 2030,” he said, “but new cycle lanes that take up so much of the road has hardly anyone using them.

“In some ways the M8 has been a victim of its own success but I just can’t ever see it being scrapped.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe