I like a good window seat. My favourite is on the west coast of Mull but, then, a lot of my favourite things are on the west coast of Mull.

Through the lens of an evening whisky glass I watched clouds lying in tiers between the sea and the evening star – pale grey, ochreous pink, smoky blue – a transient geology of the sky. Time to draw breath, rewind the day and let it unspool again.

The dawn had been a reveille on massed snare drums, with gale-driven rain and hailstones on glass, tantrums on a tin roof. So breakfast was slow and lingering, a second coffee by the window while I let the day tire of its early gusto.

I was here to write, so I lingered over my notebooks, watched from the window seat as the wind and rain slowly wearied and the clouds shrugged into life.

Mid-morning, I walked to the shore, shouldering aside gable-ends of Atlantic winds.

A heron stood on one leg, contriving to look carefully comatose, purposeful as a lighthouse. I thought of Sorley MacLean, an island poet, he had seen this situation thousands of times and memorialised once.

A demure heron came

and stood on top of sea-wrack.

She folded her wings close in to her sides

and took stock of all around her.

Alone beside the sea

like a mind alone in the universe,

her reason like man’s –

the sum of it how to get a meal.

On an island shore, a headland north of Crackaig of the wild ash, the colour of grey might have been invented so a heron might wear it.

The village of Crackaig was abandoned during the latter part of the Highland Clearances in the 19th century, yet memories remain.

If you were to gather up all the evidence of that lost habitat of man from the window seat I had just left and the roofless window seats of Crackaig, then seek out a symbolism for it among what remains here, your eye might alight on that ankle-deep heron and marvel at such a living monument.

Mid-afternoon, I had returned to the window seat. Window seats have seen it all. This one has seen generations of golden eagles fledge and fly and hunt from an eyrie with a view of Staffa and the Treshnish Isles. I had not seen them that morning but they were about to put indelibility on the day.

The cottage door was open, the air up from the sea, bearing the scents of half the world’s ocean winds into the room and laving the window seat, which is where I suddenly became aware of the air.

It drifted into the room from just beyond the door with a kind of restrained urgency intrusive and familiar. I knew that voice. What on earth…?

Then something snapped into focus. I ran for the door, grabbing binoculars as I ran – it was a young golden eagle.

A hundred yards away, 100 feet up the hillside, three golden eagles leaned into the wind, and one of them was yelping like a stuck pig.

The birds were all but stationary against the flow of air – working the thermals, half-furled wings up-curved, their positions like the points of an arrowhead, up-tilted.

One further back was the yelper, wearing the white underwing patches and white tail, the badge of the apprentice. Three golden eagles moved off as one, and by the apparently contradictory device of resetting the tilt of their wings and pulling them in, without a wingbeat. But at once they eased forward against the wind.

Covering a mile in less than a minute, fanning out of formation, they began a spiralling scrutiny of the hillside facing the window seat.

But once again they formed up against the wind, a diagonal of three. So I returned to the window seat and watched and wondered and admired.

Mid-afternoon, walking the comparatively green miles of a raised beach – a situation I love, cliffs above, sea far below – the shrill staccato voice of a peregrine falcon shattered the mood.

I found a young bird, a flying scythe, kestrel-hued which can be especially confusing if it hovers and keeps its mouth shut. But this one was particularly vocal, which suggested it was aggrieved at the presence of a greater threat. It turned out to be the young golden eagle, the yelper of the morning, whose leisurely flight wafted across the cliff face.

The falcon got louder and bombarded the eagle’s airspace, but doubled back in the face of the eagle’s indifference, and still at the same breakneck speed it had a head-on near-miss with the largest, darkest golden eagle I’ve ever seen, and with the most golden head.

I have no idea where the peregrine went, for the eagle was so close she filled my binoculars, she became the beginning and the end of my world – a golden eagle to define the bird’s every characteristic.

She traversed the cliff with a kind of serenity, 20 feet below the skyline, 50 feet above my rock perch, eternal as Staffa, and bird and island became fused in my mind.

Her dark permanence, her beauty, her profile and her presiding spirit are all qualities that Staffa harbours, and I had been watching Staffa all along the raised beach, a kind of island-forever in my mind.

She was directly overhead when she dipped a wing and edged in towards the cliff, perching precisely by her mate. He had been there the whole time, rock-still and rock-hued, I had simply not seen him.

They stood inches apart, and she dipped her head to preen, so that her dark-brown bulk was suddenly rakishly topped by the gold blaze of feathers on her head and nape. The illusion of a crown was irresistible. For the first time in my life I understood the possibilities of idolatry.

Then she spread her dark cloak of wings, and leaned on the island air. Her mate followed, and their shadows ghosted in and out of the cliff’s gullies and buttresses.

They were gone and I was earth-bound and stupefied.

So that was what I had taken to the window seat and the whisky in the dusk, and why it was a long, slow darkening of the island north that I watched, thoughts on golden eagles, and when I moved at all it was only to refresh that other golden hue in the glass in my hand.

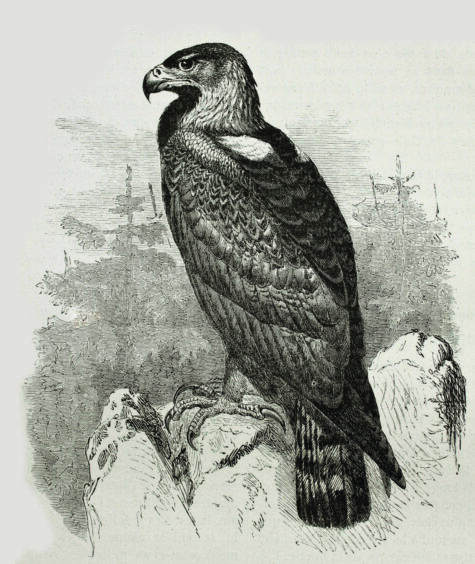

Documenting the great eagle

Seton Gordon, Scotland’s definitive golden eagle authority, was among the first to observe the bird in some detail. In his last eagle book, published in 1955, he wrote: “It is a long time ago – April, 1904 – since I photographed my first golden eagle’s eyrie.” Imagine the camera!

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe