IF you think you know everything there is to know about the officers and gentlemen of the Great War, a new book will make you think again.

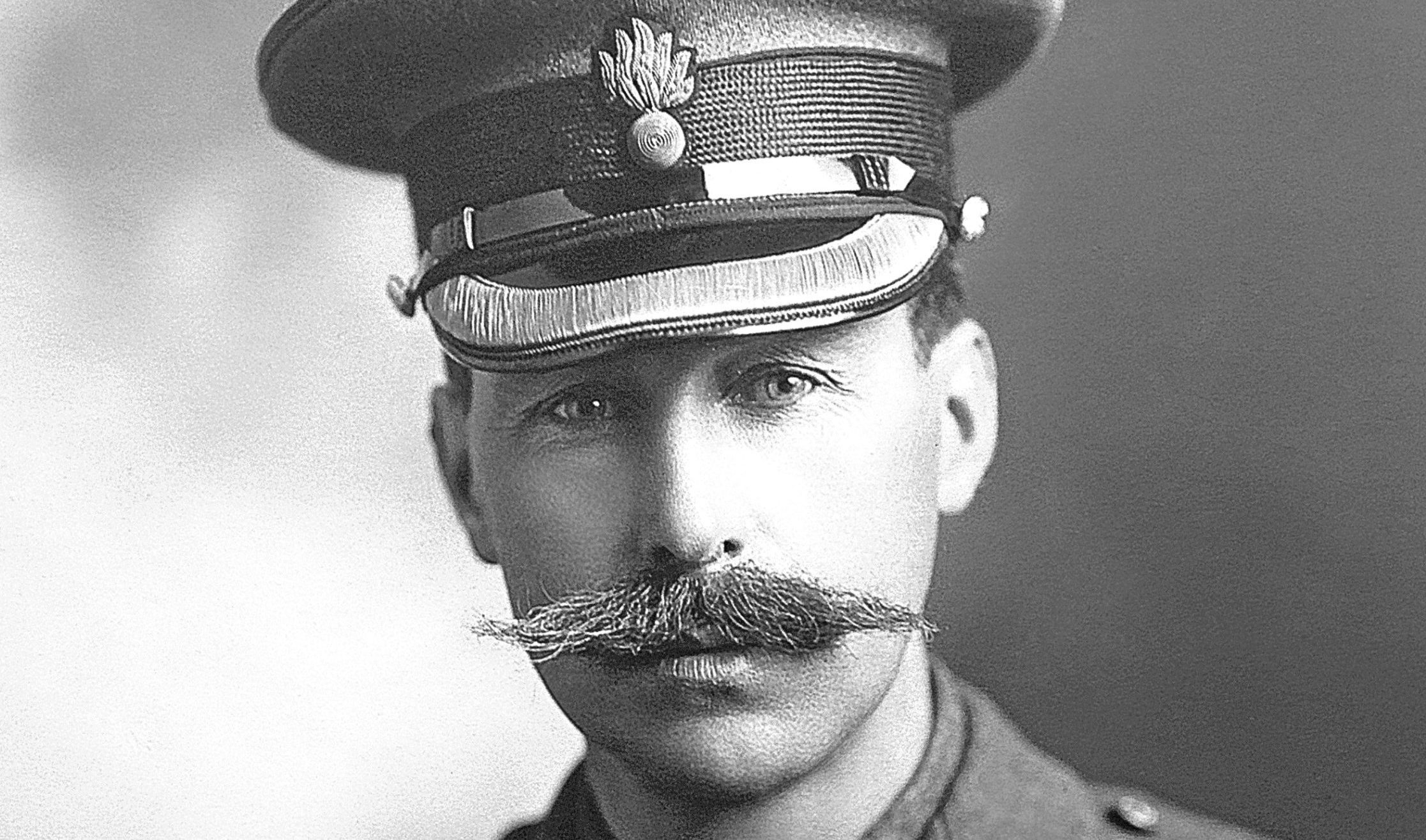

Lt Col Wilfrid Abel Smith commanded 1,000 elite British soldiers during the First World War, and was one of the most-outstanding officers on the Western Front.

Educated at Eton and Sandhurst, he was a career soldier with the Grenadiers.

The book was written by Wilfrid’s great-grandson, Charles Abel Smith, who was also educated at Eton, and is the first member of his family to have gone back to their earlier banking roots, rather than joining the Grenadiers himself.

With his book, he more than makes up for it, having written lovingly about the remarkable Wilfrid, and earning plaudits from world-renowned war historian Antony Beevor.

“It was very much a tradition in the Guards that officers were taught to look after their men before they looked after themselves,” says Charles proudly.

“Officers made sure their men were comfortable first.

“When writing the book, I wanted Wilfrid’s letters to be seen, without me getting in the way too much.

“Towards the end, when he was killed, he was clearly quite nervous about what he was being asked to do.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever been to see that part of France, but they were asked to attack across a completely flat piece of ground. I walked out to within 50 yards of where he was shot, and it was absolutely flat.

“He went out there, aged 44, for nine months of fighting and two weeks’ leave, during which he had to come home and sort out all his affairs.

“I don’t think any of us can imagine what it must have been like to live through that, with the constant shelling.

“Wilfrid was so close to home, yet so far away.

“You could be back in Britain in 12 hours, but there you were in the trenches, the next best thing to Hell.”

One thing that powerfully comes across in Charles’ book is the sensitive side of Wilfrid and the fact that far from being a posh bloke who kept out of harm’s way, he put himself in the line of fire.

Sadly, he paid the ultimate price for it, and it is wonderful that Charles will ensure his heroism will never be forgotten.

“He must have been a remarkable man, because as a professional soldier he would have been a strict disciplinarian, classic textbooks Guards officer,” Charles admits, “but his humanity comes through in his letters.

“The way he talks about his men in letters to his wife and children, and then the condolence letters written by his own men after he died are quite extraordinary, too.

“Particularly with the coverage of the Somme, it is usually all about the mass deaths.

“But within all of that, there were humans from all walks of life, their stories of human endeavour.”

Wilfrid’s letters home also speak with amazement about the new technology he was coming up against in the trenches, his awe at planes flying over them, Zeppelins attacking Britain at home, and tanks being seen for the first time.

“There was the emergence of new technology, being trialled,” Charles points out.

“It must have been the world’s first industrial war.

“At the same time, there was still basic communication equipment, and you forget how hard it was to command people.

“Most of it was still being carried about on pieces of paper by messengers, one of the most-difficult jobs.

“They had to adapt. All of a sudden, fighting in trenches, you needed periscopes. Then there was gas, and how you responded to that. A handkerchief in your mouth was all they had and it took a while for that technology to improve.

“The tin helmet still wasn’t invented at the beginning, and all they had was the cloth cap!”

Mortally wounded when he was shot in the head during the Battle of Festubert, on May 18, 1915, Wilfrid died the following day, having never regained consciousness.

And yet his last letters show he was a sensitive, thoughtful man to the last, even when he could see what mortal danger he and his men were in.

“It was a glorious day yesterday,” Wilfrid wrote home, “and it is odd how little the animals of nature care about a fight.

“The birds were chirping as if nothing was happening, the bumble bees were buzzing about, and the bugs, flies and mosquitoes.

“A glorious blue sky, with our aeroplanes going backwards and forwards like huge eagles, and the trees all getting their summer garb — while man was doing his very best to destroy everything, and succeeding!”

A new German line went undetected and the 4th Guards Brigade, with Wilfrid’s battalion, advanced late in the afternoon, towards Ferme Cour d’Avoue.

Met by relentless machine gun fire, and with nowhere to hide, Wilfrid was hit and the attack was called off.

There would be nearly 17,000 casualties during the first four days of the battle, with 11 officers perishing along with one brigade commander.

Although the British forces managed to advance up to 1,300 yards, in most cases all they found were more German lines and another battle needing fought.

“A lot of Great War history has been tucked away for many years,” Charles points out.

“If you find something like Wilfrid’s letters and can hear his voice, it’s wonderful.”

From Eton To Ypres, by Charles Abel Smith, is published by The History Press, ISBN No 978-0-7509-6635-1, priced £20.

READ MORE

Graffiti from imprisoned first world war conscientious objectors to be saved

First World War Tommies spent just half their time at the front

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe