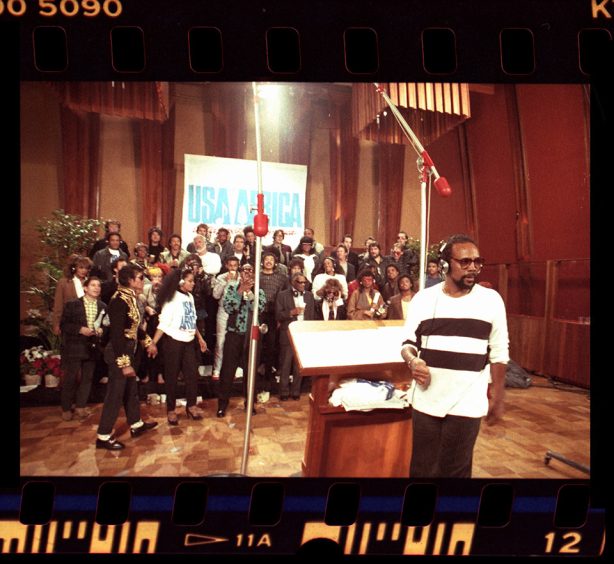

It was the evening when America’s biggest stars gathered in one room for what became known as the Greatest Night In Pop – and it was all captured by the greatest Scottish photographer.

Cameras rolled in January 1985 for the recording of USA For Africa’s song We Are The World, America’s charity single in response to the Ethiopian famine of the mid-1980s, capturing incredible footage of a moment in time that has become a hit documentary almost 40 years later.

American titans of music, including Michael Jackson, Diana Ross, Bob Dylan, Cyndi Lauper, Bruce Springsteen, Tina Turner and Stevie Wonder, came together in Los Angeles in the wee small hours of January 28 and 29, after the American Music Awards ceremony, to record the Stateside answer to Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas?.

Extraordinary film of the recording session, cut together in Netflix’s 2024 documentary The Greatest Night In Pop, reveals struggles and tensions during a high-pressure one-shot superstar-choir session led by Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie.

And it also reveals a Glasgow boy, who learned his craft on Scottish newspapers, capturing images at the epicentre of the showbiz world that night.

‘They knew it was going to be a tough night’

“I wasn’t thinking about being filmed or photographed when I was there,” said Harry Benson, speaking exclusively to The Sunday Post about one of the most famous nights in American entertainment, 39 years later. “But it was nice to see myself in the documentary.”

Harry was working for prestigious US magazine Life when he was asked to cover the event in LA’s A&M Studios with the late journalist Cheryl McCall.

“She was a good friend of the producer and, being a Life reporter, it wasn’t unusual to do those sort of stories. She got in and she got me in and more or less nobody else. It was the way it worked out. They didn’t want journalists and photographers in there because they knew it was going to be a tough night.”

The documentary, which was released earlier this year, shows just how tough. Lionel Richie reveals his nerves about whether his fellow megastars would even turn up to support the song.

And the ones who did turn up in a fleet of limos – a stellar cast featuring luminaries like Billy Joel, Kim Carnes, Willie Nelson, Dionne Warwick, Bette Midler and Smokey Robinson – were beset by performance anxieties.

One memorable scene shows Kim Carnes, Cyndi Lauper and Huey Lewis struggling to nail a threepart harmony on the track, written by Jackson and Richie, and produced by the legendary Quincy Jones. “It wasn’t an easy song for them,” said Harry. “It took them a while to get it right. We didn’t even know if it was going to work out. We’d be hearing sporadic good singing mixed with terrible singing, and you’d think, ‘How are they going to get this together?’. But it worked out.

“One or two walked away. It was as if they were thinking, ‘I can’t take any more of this’. And Waylon Jennings (the country music star) left because he didn’t want to sing certain bits of the song.

“But I was there all night. We were still there at 5.30 in the morning. I left about six and there were still some there wanting to get it right, their little part in it, especially Michael Jackson.

“I remember thinking his voice wasn’t great at first. But he was a big part of the song, and when they had problems he pulled it all back again. Michael kept them together.

“Although I remember Diana Ross joking at the end of the night that the white boys were really kicking ass.”

Despite the tensions on the night, the single went on to be a global smash, becoming the biggest-selling American single of the 1980s, raising the present-day equivalent of $200 million for aid in Africa.

Harry said: “It all worked from my point of view because we do what we do – we are inclined to stay to the bitter end. Some other guys might think they’ve got enough and go early, but when you stay until the end you pick up other things.

“Often it’s the last 20 minutes that are very important, and that’s true here because they got the song right.”

Another of the documentary’s most candid moments is the capturing of Bob Dylan’s look of bewilderment. Harry has his own take on that.

He said: “Dylan likes to do that to be different. They knew about his ego, and how he likes to draw attention.”

Harry’s still snapping

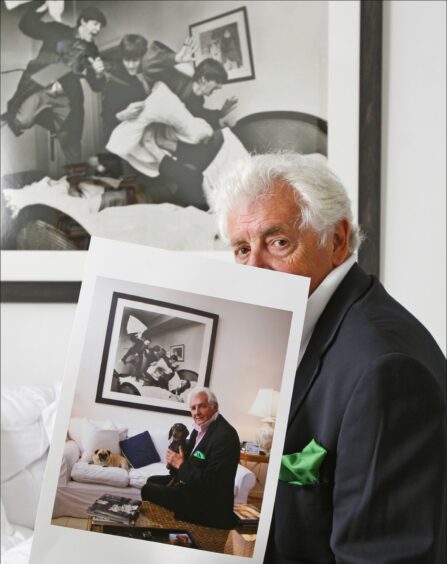

Harry, now 94, says he still “picks a camera up every day” and is working on a forthcoming book of images of Sir Paul McCartney. Currently over-wintering in the Florida Keys, away from the spring cold of his New York home,

Harry and wife Gigi plan to visit Scotland later in 2024.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Harry’s first of many assignments with The Beatles in 1964, during which he captured the iconic images of The Fab Four having a pillow fight in a Paris hotel.

He said: “The BBC had been up in the room and Paul was giving probably a very pompous interview about the music, and John comes up and bangs him on the head with a pillow. But the BBC didn’t pick that up. As soon as they left the room with their cameras, I said ‘how about a pillow fight’.

“They said they’d look childish, and John said, ‘We can’t go round the world looking silly’. They all agreed, then John slipped away and came back and hit Paul on the head with a pillow. And that gave me a good picture.”

Among the others of his countless iconic images is that of the stricken US presidential hopeful Bobby Kennedy, murdered 60 years ago by Sirhan Sirhan.

Another, of Donald Trump, shows the ex-president flaunting his wealth. “He would do anything, Trump,” said Harry. “I once got him holding a million dollars. He did it, but it’s the last thing you should be photographed with. It doesn’t look good.”

After 70 years with a camera in his hand, in a stellar career that led to a CBE in 2009, Harry’s advice to aspiring photographers is simple.

“Dress the best you can,” he said. “If you dress casually people can interpret that as you think they’re not worth putting a tie on for. That made perfect sense to me – dress well and you show respect to a person.

“Apart from that, I was always just looking to stay on the payroll at the end of the week.”

The Greatest Night In Pop is available now on Netflix

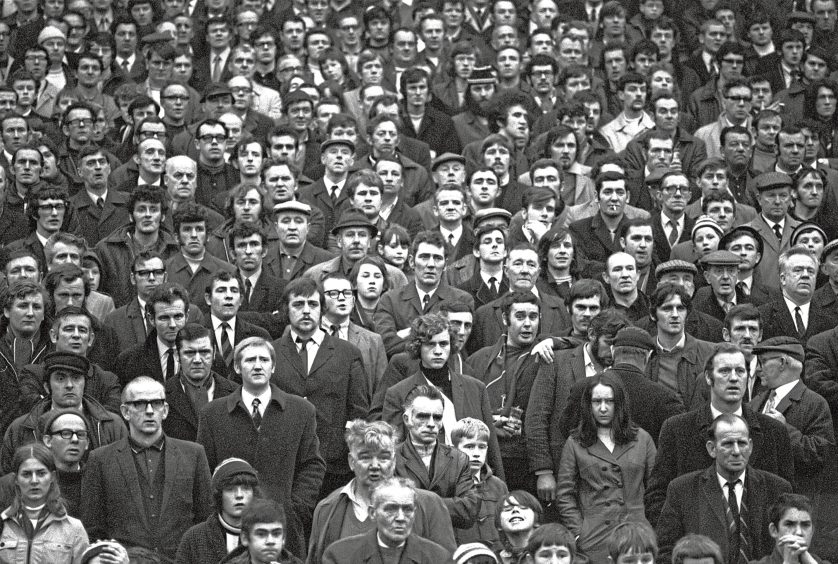

A familiar face in the very large crowd…

By Paul English

The picture was so large we couldn’t see it for looking at it.

When Harry Benson’s Glasgow exhibition was unveiled at the city’s Kelvingrove Museum in 2008, it was an English family night out.

Browsing the legendary photojournalist’s immortal shots of his hometown from the 1960s to the 2000s, we’d somehow missed the most personally significant one of all.

My mother Kathleen was stunned when she spotted the image of her brother, Pat Breslin, blown up for an oversized roof-to-floor frieze on the back wall of the exhibition.

When I showed Harry the picture last week, and explained he had captured my godfather looking nervous in the crowd of a Celtic v Rangers game in the 1960s, surrounded by a posse of fellow Port Glasgow Celtic fans, many of whom are now dead, he said: “Good Lord, really? Well tell him he’s the best-looking one there.

“When you examine the faces, you see the tension of the game and you can tell from the photo that football is a serious thing. It’s not to be taken lightly in people’s lives. Myself included. I’m very pleased there’s someone in that photo I’ve made contact with all these years later, even indirectly.

“Tell him Rangers were getting beaten 2-1, don’t tell him they were winning…”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Harry Benson

© Harry Benson

© Ian Rutherford/Shutterstock

© Ian Rutherford/Shutterstock © Harry Benson

© Harry Benson © Harry Benson

© Harry Benson