Neil Forsyth, the creator of Bob Servant and Guilt – and Dundee United fan – salutes the incendiary genius of the club’s legendary manager, Jim McLean, after his death on Boxing Day at 83

My great uncle Bill was perplexed. Which was unusual. A retired bank manager in Broughty Ferry, Dundee, Bill was a reliably genial man. He bought us our weekly copy of Roy Of The Rovers. He pretended he had a motorbike. He taught us a disappearing coin trick that, when I bravely attempted to recreate it, led to a frantic journey to Ninewells Hospital, an X-ray lamp and my traumatised mother spending weeks grimly sorting through my despatches.

But on this day, sometime in the late 1980s, there was no magic trick, or imaginary motorbike, or Roy Race. Because Uncle Bill was perplexed. Worry rampaged through his days and into his sleep. My Aunt Sadie had found him muttering in the darkness. The source of his troubles was an unfolding crisis. And it was unheard of.

Broughty Ferry Bowling Club, a grassy enclave on Albert Road, was historically a model of serenity marked by the clicking of bowls and hushed conversation. Uncle Bill was on the committee. They respectfully discussed buffets, raffles and umpire rotas. It wasn’t a difficult gig. Uncle Bill had been in the War.

But there was a problem. A rogue member. He had been welcomed with some fanfare a few years before but now, well, now the trumpets had fallen silent. Because this member, this member was different. This member disputed decisions, berated team-mates, antagonised the opposition and queried the workings of the bewildered groundsman. This member arrived at matches taut with tension and only grew more so. This member saw himself as the victim of a dark conspiracy lurking behind the masking smiles of Broughty Ferry retirees.

There had been whispers of objection. And then there had been complaints. And now there was a crisis. There had been a meltdown. An outburst on the greens. A wheeling, pointing, multi-faceted onslaught of anger and accusation that, the way it was told, had seen onlookers running for cover, elderly limbs reawakened by primal self-preservation as they leapt over walls in a search for shelter.

The inquest had fallen on the broad, war-hardened shoulders of Uncle Bill and left him muttering in the night time. He had tried everything. Sit-down chats. Jokey de-escalations. Arms around shoulders. Appeals to better angels. None had worked. The impasse had hardened. The anger, if anything, had festered and grown.

And now, on a sunny afternoon in Broughty Ferry sometime in the late 1980s, Uncle Bill was at his wits’ end. He had nothing left. Nothing but a final, plaintive, visceral call for sanity.

“I said to him,” Uncle Bill told me, his kind face frozen in confusion, “Jim, why don’t you just calm down?”

The opening chapter of Jim McLean’s autobiography Jousting With Giants is McLean in microcosm. He starts by declaring his lifelong inferiority complex (the title was a clue), then has an entirely unconnected, furious pop at the press for never giving enough credit to United’s utility man Billy Kirkwood, followed by an entirely unconnected, even more furious pop at Dundee fans for the stick he got during an unhappy period at Dens Park as a player.

The innate sense of grievance, the smouldering anger, the capricious, relentless hunt for injustice. Here comes Jim McLean.

He was a distinctively average footballer. The stick from Dundee fans came at the tail end of a career that was ready to end. For several years, McLean had spent his summers building houses. When he retired his plan was to do so full-time, yet instead he received the unlikely invitation to stay at Dens as part of the coaching staff.

He gained a reputation for hard work, discipline and innovation. In his book he talks about overseeing the players’ “conditioning”, and studying West German football for tactical guidance. His reputation drifted down Tannadice Street. In 1971, Dundee United’s long-serving manager Jerry Kerr stood down. McLean applied for the job, and was horrified to get it.

Instantly, he felt the roaring arrival of the nerves that would plague his managerial career. The pressure, the tension, the invasiveness of public attention. In short, the paradox of Jim McLean. A wonderful, daring football manager, whose teams played joyously attacking football and spread happiness for decades, but a man who spent those decades in a state of self-imposed sufferance.

On paper, his managerial career started slowly with mid-table finishes and no hint at future success other than United’s first Scottish Cup final (and the first of McLean’s six Scottish Cup final defeats) in 1974. But this was a time when managers were allowed to shape careers, and the league table only told half the story. McLean, after all, was a builder. In those early years, he was laying a foundation.

As his team steadily assembled, McLean added a tactical nous matched only by Alex Ferguson in modern-day Scottish football. Obscene levels of fitness and organisation, a militantly observed twin objective of “win the ball, keep the ball” and a constant fluidity of formation.

Finally, success arrived. In 1979, United won the Scottish League Cup, beating Ferguson’s Aberdeen in the final. For the players, for the fans, for the club it was revelatory. We could win things. McLean found long-serving director Ernie Robertson weeping in the boardroom, bewildered by the club’s first major trophy after 70 years of existence. A year later, they won their second, retaining the cup by beating Dundee at Dens Park on a pitch so frozen that Davie Dodds wore a pair of Adidas Sambas.

For the players, the arrival of success was a blessing and a curse. It justified McLean’s tyranny but it also trapped them within its orbit. They were the cornered cadre of a dictator, gaining riches and scars in equal measure. But they knew that McLean was entwining them into a force greater than their parts. That the volcanicity of his anger caused a rising tide that lifted all boats.

By 1982/83, United were firmly established alongside the Old Firm and Aberdeen as one of the nation’s top four clubs, but had yet to finish higher than third in the league. And it didn’t look like that would change. In January 1983 they were third and out of all cup competitions. Yet an accelerating run of victories would see them play Dundee at Dens on the last game of the season for the chance to win the Premier League.

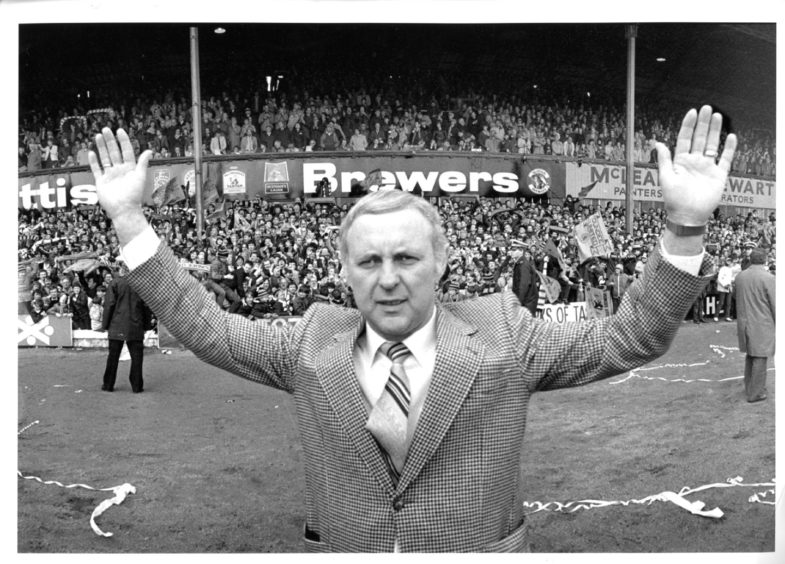

United won 2-1, setting a new scoring record for the league in the process of winning it. It was a miracle. At full-time, United’s players lifted their messianic leader upon their shoulders and McLean found himself with no emotional choice other than a reluctant disclosure of happiness.

When he was persuaded to fleetingly break with his teetotalism to sip Champagne from the trophy for the TV cameras, he said with genuineness that he hoped his mother wasn’t watching.

People often remark with surprise that Richard Griffiths was only 39 when he played Uncle Monty in Withnail And I. Well, look at McLean when United won the league. He looks old, but he wasn’t. He was 46. And he was only just starting.

We live in a time riven with superficiality and fleetingness. Newspapers, books, prolonged moments of mental silence, all swamped by the urgent irrelevance of social media. Football has changed accordingly. The deification of instant gratification and dismissal of patience means that clubs are a churning bowl of personnel. Testimonials, once a pre-season flurry, are rare events. Managers come and go so rapidly you can forget they were ever there. A slow-burn success would be extinguished long before it sparked into life.

Jim McLean represents a different time. A time of permanence. A time when, for an entire childhood and teenage years, your football club could have one manager. Time passed slowly under McLean. Seasons came and went as he stood glowering at the side of the pitch, feathering the nest of his legend. For my generation, his impact was formative. He was how we saw football. He was how we saw manhood. And the game doesn’t make men like that anymore. There isn’t the time.

“Jim,” asked my Uncle Bill, “why don’t you just calm down?”

He couldn’t calm down because he was a coiled spring of hunger and anger and determination, who rose in the morning wounded and seeking revenge. And his revenge was to take a provincial football club and drag them to domestic glory and on to impossible foreign adventures. His revenge was to give an awed set of supporters a set of experiences that would mark heavily upon their lives.

He taught us to fight against the natural order. He taught us that the world, that vast, murky, unknown pre-Internet world, was not to be feared but to be invaded and conquered. He taught us that our club mattered. That our city mattered. That we mattered.

I’m so glad he didn’t calm down. I’m so glad he raged and fought and scrapped and roused a band of men into feats so far beyond them. And I hope it didn’t cost him too much.

And I hope that Jim McLean remembered. I hope that he remembered who he was. I hope that he remembered what he did. And I hope that he knew he was a hero. Like all men, he was many things. But Jim McLean was a hero.

A longer version of this article first appeared in Nutmeg, the Scottish football magazine, in March 2019. It can be read on the Nutmeg website.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Unknown

© Unknown © SNS Group

© SNS Group

© Kim Cessford / DCT Media

© Kim Cessford / DCT Media