It starts with 16 seconds of incendiary rhetoric from civil rights attorney Thomas “TNT” Todd… and then it gets serious.

Public Enemy’s Fight The Power was an instant hip hop classic but, 33 years later, its beats, loops and an impassioned call for revolution still reverberate.

Now Chuck D, Public Enemy’s frontman turned elder statesman of rap, is fronting a landmark BBC documentary called – what else? – Fight The Power, charting how hip hop has changed lives from the Bronx to Bargeddie.

Darren McGarvey, hailed as one of Scotland’s most important thinkers on class and equality, believes hip hop’s importance cannot be overestimated.

The author and campaigner, named one of the world’s 50 most important thinkers by Prospect magazine, first came to public attention as rapper Loki and hip hop stars like Wu-Tang Clan, Gangstarr and Nas were soundtracks to his political awakening as he watched MTV Base growing up during a chaotic childhood in the ’90s.

“I gravitated to it because it braids together writing, speech and performing,” explained McGarvey, author of The Social Distance Between Us. “And in hip hop culture, it’s about authenticity.

“Suddenly experiences I was previously embarrassed about, like my mum being a drinker or not always having the nicest clothes, became legitimate things I could write about that would get me a lot of respect.

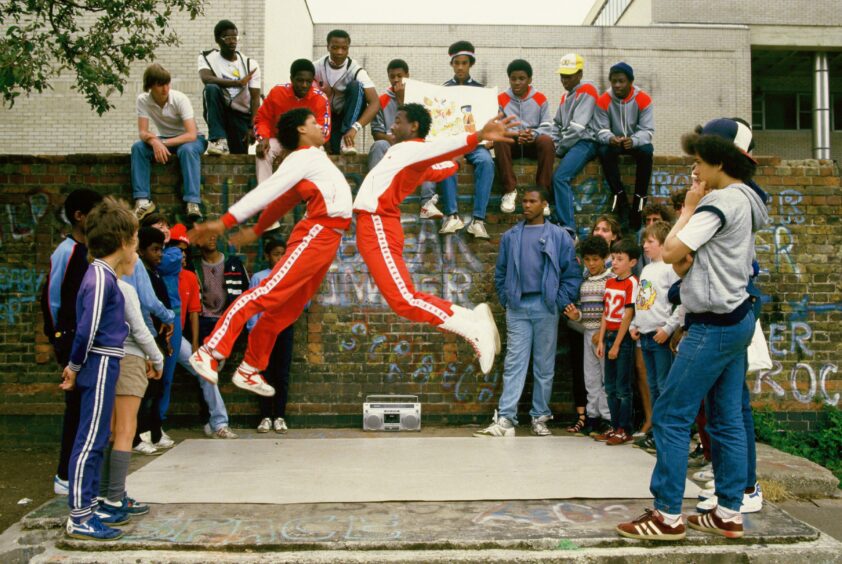

In Fight The Power, Chuck D examines how hip hop originated in poor black communities in New York. MCs with turntables and speakers hosting block parties brought together communities where issues like poverty and racism would inevitably be examined; it helped spawn its own culture which spread around the world.

“It’s more than just block parties,” added McGarvey. “This was a social and cultural movement which was taking back control over the narrative around African Americans in the big urban centres.

“Walls became canvases, pavements became dancefloors, and old turntables and vinyl became a whole new musical aesthetic. This all shone a light on institutional racism, gave voice to new leaders and artists, and exposed and challenged police brutality whilst also reporting from the deprived communities themselves, lending context to stereotypical headlines.”

Doctor Justin Williams of Bristol University is a hip hop scholar who specialises in examining the relationship between the genre and wider culture, and he agrees with McGarvey. He pointed out that hip hop remains a vital form of protest music today.

“Hip hop may have began as a party music, as an escape from conditions of poverty and gang warfare in the 1970s Bronx,” he explained, “but after The Message by Grandmaster Flash And The Furious Five, it showed the potential of rap music to speak to social conditions and lived reality of black and brown people in New York City.

“From there, hip hop has been used as the soundtrack to protest and revolution, from the ‘Arab Spring’ in the Middle East to Black Lives Matter, even to the referendum for Scottish Independence.

“A lot of the politically tinged music of the Scottish Independence campaign in 2014 was also used by the BBC for some of its coverage.

“So I think that’s the more interesting part of the story, is that the BBC was using homegrown hip hop artists, as opposed to US ones, to help tell the story of the referendum, artists like Stanley Odd, Hektor Bizerk, and Loki were important voices, and demonstrated the power of hip hop to be used for political debate.

“As I wrote in my book, Brithop, hip hop has provided a voice and a counternarrative for more mainstream voices covered by the BBC and elsewhere.

“Elsewhere in the UK, London-based artists like Dave or Stormzy have also articulated sentiments around immigration policies, the police, and the effectiveness of the government to take care of marginalised peoples.”

In the United States, where Black Lives Matters protests have taken place over the past few years, hip hop artists have tackled Donald Trump’s rise and the murder of George Floyd by white police officer.

The genre has evolved since the days of Chuck D’s inflammatory rhymes, according to Dr Williams. From revolutionising a racist society, some artists are increasingly turning inwards.

“A song like How Much A Dollar Cost by Kendrick Lamar covers the importance of compassion through a compelling story, with a lot of theatrical delivery almost as vivid as a play,” he said, “with a beautiful musical background to help give emotional weight.

“With Kendrick’s new album he’s really talking about self-care and mental health, which show all the things that can happen with racism, politics, and fame. This has given Kendrick the conclusion that he should take care of himself and his family before anything else.”

Rapping about self-care doesn’t mean hip hop is losing its power to change the world, though. According to McGarvey hip hop culture can still be a vehicle for social change

“Hip hop creates a focal point for a community,” he explained. “It creates a diversionary activity for young men and women, something to aspire to and take serious pride in.

“It might not be headline worthy, but every day I see it create change in people’s lives, like it did in mine.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Clare Muller/Pymca/Shutterstock

© Clare Muller/Pymca/Shutterstock