Murray Pittock, one of Scotland’s leading historians, explains why there is

still much to be done to improve the teaching of the subject in schools and encourage a greater awareness of our past to help prevent it being hijacked by both sides in the constitutional debate.

Scottish history is taught more in the secondary school curriculum than was the case 30 years ago and is now just over a third of the marks in Higher history.

Yet former Conservative Secretary of State Michael Forsyth’s 1996 plan to introduce a Scottish history Higher, and the findings of the 1998 Scottish Culture and the Curriculum Report, which showed that 97% of respondents wanted an emphasis on Scottish history and 93% on Scottish literature, remain unachieved after 15 years of SNP government.

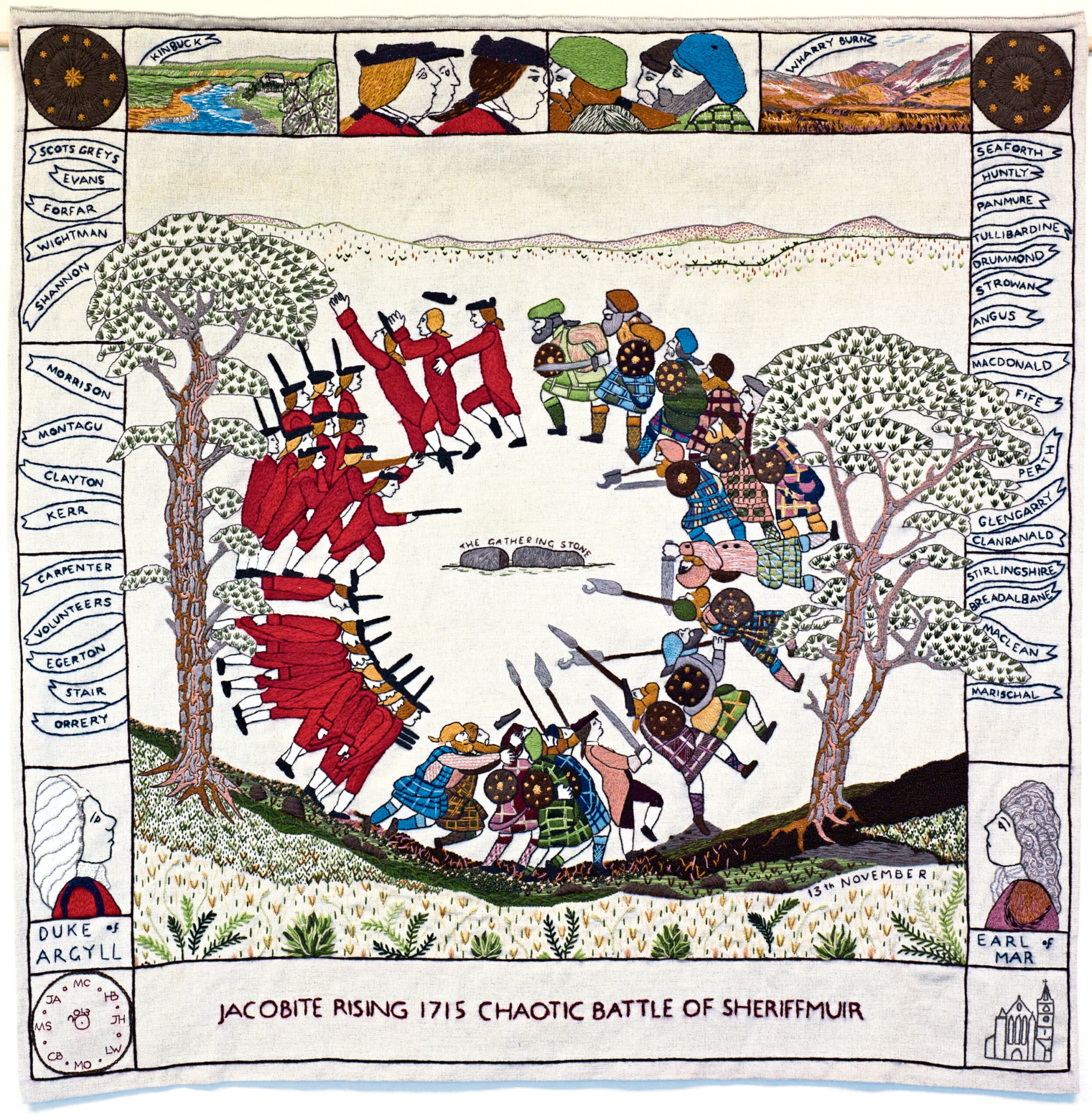

Even the praiseworthy Scottish Studies initiative launched in schools from 2011, for which I chaired the national champions’ group, has withered on the vine. Perhaps because of this, when the Great Tapestry of Scotland was unveiled, research showed that almost half of those who claimed to know “a lot” of Scottish history thought Macbeth was a character in a Shakespeare play. In other words, English literature invents Scottish history. We do not take ourselves seriously.

This is the paradox of Scotland and its history. It is fashionable and even addictive worldwide – witness Outlander (which has brought millions of pounds in tourist industry to Scotland) among many other examples – but it is not core to the learning experience of many at home.

And yet, people want to know. Famously, Sir Tom Devine’s The Scottish Nation briefly outsold JK Rowling at the height of Harry Potter’s popularity, while Michael Stewart’s (“HRH Prince Michael of Albany”) neo-Jacobite claim to the throne in Forgotten Monarchy reached No 5 on Scotland’s bestseller list.

At university, many students are engaged passionately in discovering their history or literature for the first time. This is very rewarding for them and their teachers: but nonetheless, this should not be the first time that young people encounter their history or their culture.

The lack of that culture and the appetite for it can be seen far beyond bookshops. Initiatives such as the Great Tapestry of Scotland help bring a strong visual linear history of the country to a wide community audience, while the presence of magazines such as History Scotland demonstrates how a mass-market magazine can sustain itself on what seems to some to be such a specialist topic.

Ignorance leads to poor choices and feeds conspiracy theories and fake news. This happens on both sides of the political divide. The adoption of the 1820 “Radical Rising” by Scottish nationalism after 1967 is one of the early examples of the development of a historical myth. Among the leaders of this “Rising”, which was closely linked to Peterloo and English radicalism, only ex United Scotsman James Wilson with his “Scotland Free or a Desart” banner seems to have reflected Scottish national rather than British political and economic differences.

But the search for left nationalist ancestry has inflated this relatively small and geographically limited economic and political protest. Frank Sherry’s The Rising Of 1820 (1968, with a foreword by Winnie Ewing, who had just won the Hamilton by-election) situated the Rising as an avatar of popular left-wing nationalism, a role it retains.

Similarly, the events in George Square, Glasgow during the January 1919 strike which led to the Sheriff of Lanarkshire requesting military aid (including the famous tanks) have long been deployed to bolster an inflated assessment that this was a potential radical uprising and not a protest for better conditions.

It is not that either of these accounts are fake news in the modern sense – they are not downright lies but they are neither proportionate nor comparative. Troops were used in Liverpool in 1919 to prevent disorder without creating the story of the Red Mersey; in 1820, the supporters of the Rising invoked Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights, both core English texts. George Square in 1919 and the Battle of Bonnymuir in 1820 are both Scottish history but they belong to a wider context too. And it is a context where Scotland has been an actor, not just a victim, as with the transatlantic slave trade.

Unionists might want to call this British history but often that is equally if not more lacking in proportionality and balance. The unionist language of today has frequently changed from the celebration of Scottish culture to its negation.

John Buchan was a champion of Scots, a language which many unionists – despite support for it by Conservative and other governments, its central role in the global Burns movement and the presence of a national dictionary with 100,000 words – claim does not exist. British politicians claim there was no real border between England and Scotland, though it is perhaps the oldest border in Europe, all but a few square miles having been resolved since the Quitclaim of York in 1237.

There are many more denials or extraordinary reinterpretations of the Scottish past on show: a reversal of the unionist tradition which once supported Scottish history and literature.

The intensity and power of Scottish networking was socialized and supported abroad from before 1800 to after 1950 through St Andrew’s and Caledonian Societies and later Burns Clubs: there were more than 1,000 Scottish societies throughout Britain and its Empire in the late Victorian period, all to a greater or lesser extent dedicated to promoting Scots at the expense of non-Scots worldwide.

Even today, 9.5 million attend Burns Suppers every year. Scotland’s culture was central to these societies, which promoted “a taste and love for Scottish music, history, and poetry”.

St Andrew’s Societies events celebrating Scottish history involved up to 2,000 people. At the 1879 Waverley Ball at Shanghai, guests dressed as characters from Scott’s novels while at the 1921 St Andrew’s Ball, as reported in the North China Daily Herald, clan shields hung on the walls together with Lochaber axes and quotes from Burns and Scott.

Burns and Wallace became core Scottish icons for consumption in the British colonial world, and were central to a desire to spread Scottish culture among the diaspora to maintain their links with the old country. Prizes were offered for Scottish history and poetry and Scots in Africa funded a bursary to pursue the study of the “glorious history” of Scotland, while at the 1888 Glasgow Exhibition there was a vast display of the whole range of Scottish history and that of 1911 foregrounded the cultural achievements of the country.

And, of course, we owe our national museum, national portrait gallery and national library to the 19th and early 20th Centuries. The unionist Scot was nationalist enough then: indeed Sir Noel Paton’s design for the Wallace Monument, which showed a lion crushing a serpent, was only narrowly rejected.

This was the era that made Scotland a presence in the mind of the world, and is why the world visits Scotland today. Our friends abroad often value us more than we value ourselves.

Conspiracy theories and talking Scotland down do nothing to engage us with the world outside: they are a rabbit hole for the constitutional debate. How can unionism flourish by rubbishing Scotland at every turn? And how can nationalism flourish by presenting us as a victim culture with the achievements and crimes of an imperial past unexplored?

It may be the case that learning more about Scottish history and culture will make more nationalist Scots in the future just as it made

patriot Scots in the past: but young people hardly find nationalism unappealing as it is. The bad consequences of ignorance are everywhere in the world today; to take our place in that world, our current and future generations need to be better educated about the culture and history of this extraordinary place and love it as so many do across the globe.

Murray Pittock’s Scotland: The Global History published by Yale Books, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © www.alexhewitt.co.uk

© www.alexhewitt.co.uk